Blizzard Entertainment celebrates its 25th anniversary today, a milestone that very few video game companies achieve in a very Darwinian industry. It has survived this long, and thrived, because of a relentless emphasis on quality. The company, which has been part of Activision Blizzard since 2008, has grown to more than 4,000 employees. In the 12 months ended Sept. 30, 2015, it generated $1.6 billion in revenue and a profit of $592 million. It is one of the crown jewels of the American game business, and its StarCraft, Warcraft, and Diablo brands are known throughout the world.

GamesBeat decided to step back and look at Blizzard’s singular achievement, which started as a few college kids and grew into a corporate empire. It’s a story about a team that stayed together and grew, even as it bounced around from one corporate owner to another, and a focus on quality that was so severe that the team would often kill mediocre games on its own, rather than allow them to be released and damage the company’s good name. Blizzard has sold millions of copies of its games, its flagship brand is becoming a blockbuster film release, and the names Warcraft, Diablo, and StarCraft are household names.

A focus on quality that goes above and beyond what rivals are willing to do has served the company well. Blizzard has been singularly successful with games like StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty, World of Warcraft, Diablo III, and many others over the years. But behind the scenes, the company has canceled at least 10 major games. Most recently, in 2013 it scuttled Titan, a massively multiplayer online game that was supposed to be the next step up from World of Warcraft.

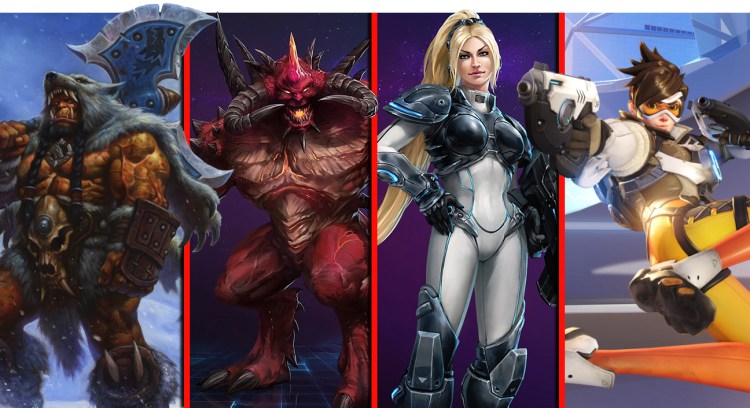

But Blizzard changed with the times and reassigned its Titan team to the next-generation team shooter game, Overwatch. And it has scored huge hits in modern game genres with its Heroes of the Storm multiplayer online battle arena game and card-battler Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft. All of these games have been designed to work well with the growing trend of esports, or competitive gaming between professional players in matches that are broadcast to spectators.

“Blizzard is perhaps the most amazing game studio ever,” said Mike Vorhaus. He has followed the game business for a couple of decades, and he’s president of Magid Advisors, a game industry advisory service and market researcher.

The common thread in many of these games is that they generate rabid fans who lose themselves in the “immersive” virtual worlds for months or years. Those fans hound and beg hound the company to come out with new material to satiate their desire to further explore these worlds.

But as companies like Nintendo have learned, Blizzard publishes games only after years of crafting and testing. That’s because the company has learned that you only get one shot at getting a game right. Even as it scaled up its teams to hundreds of people and revenues soared into the billions, Blizzard didn’t change its development process, where its developers have played, tested, and tweaked games repeatedly, even up to the point of launch.

“For its size, Blizzard has proven incredibly limber over the years,” said Joost van Dreunen, analyst at market research firm SuperData Research. “Even today it manages to outmaneuver younger and arguably more agile competitors. Its Hearthstone has earned almost $500 million since launch, and continues to add new innovations to its game play. As the company doubles down on esports and feature films, its next iteration may very well prove it to be among the top media firms in the market today, a far cry from its origins as a game maker.”

Our story is a walk through the history on how Blizzard became Blizzard.

In the beginning

The company started as Silicon & Synapse on February 8, 1991. Allen Adham, its main instigator, learned coding by working as an independent contractor. He made good money from those summer jobs during his high school and college years.

“Those were the good-old days, when one or two people could design a game themselves,” Adham said in an interview with me back in 1994. “Back then it was easy. You just had to have the desire. It was like taking an idea and writing a book. Now it’s more like making a movie, requiring seven to eight people with different skills.”

When Adham was a freshman in high school, Space Invaders, Asteroids, and Defender were the hot arcade games. He would go the arcades and play like a fanatic.

“Then my brother and I talked my dad into buying us [a computer] so we could use it for school,” he said. “We used it to play games. I liked playing the games so much that I started writing them.”

On graduating from UCLA in December 1990 with a computer science degree, Adham received $10,000 from his parents to go to Europe. But he loved video games, and he wanted to make a living making them. He used the money instead to start a video game company, Silicon & Synapse–the predecessor of Chaos. His buddy from UCLA, Mike Morhaime, also had some money from his parents. But Morhaime had a job at disk drive maker Western Digital, and Adham had to convince his friend to quit.

“Allen is a great sales guy,” Morhaime said of Adham. “I was working at Western Digital designing a little part of a chip, and he did this sales job on me for a year to recruit me.”

Adham said, “My attitude was — and this is how I talked Mike and Frank into it — we’re young, we don’t have mortgages or families. All we really have to lose is time. We could try it for a year. If takes off, great. If it doesn’t, chalk it up to experience. … I still believe to this day that attitude is everything.”

Adham was also friends with Frank Pearce, another recent grad who had a nice job at aerospace firm Rockwell. Pearce and Morhaime didn’t know each other. But their mutual friend convinced them they could make a company together. Adham had the connections to other companies, and he got them work to do.

“I attribute everything that we have and that we built to Allen,” said Pearce, in an interview with GamesBeat.

Pearce did a lot of the coding, but he also spent time serving as receptionist, answering the door and the phones in the 650 square-foot office. But he eventually grew into one of Blizzard’s most senior employees, guiding the development of some huge projects.

Morhaime, who is now CEO and took over after Adham, left, also gives great credit to Adham as the instigator.

“All three of us were programmers, but Allen was our visionary leader, lead designer, and lead business guy,” Morhaime said.

Morhaime, who eventually became Blizzard’s CEO after Adham left, was initially a support programmer, production lead, and information technology and operations leader.

“If we needed computers, I’d go to Micro Center and order equipment,” he said. “We didn’t have an IT department. It was just me.”

They worked on ports, or adapting an existing game to another platform. Morhaime recalls working on a port of Interplay Productions’ The Lord of the Rings PC game to the Amiga platform. Pearce had to draw an image of the One Ring, since that wasn’t part of the assets that they received from the publisher.

By doing that work, they came into contact with industry pioneer Brian Fargo, whose Interplay (one of gaming’s leading publishers) was also based nearby in Orange County, California. Doing work for hire is the same way that small independent developers get into the game business today. But it takes a lot of hustle, and there’s a lot of temptation to cut corners for the sake of survival.

“Our first console game was RPM Racing, and we actually started and released that project in the same year we started the company,” Morhaime said. “We managed to be on shelves by that holiday. That was also published by Interplay. The sequel to that, a few years later, was Rock ‘n Roll Racing. That was a much better game.”

RPM Racing made the company $40,000, and it appeared on the Super Nintendo game console.

The quality ethic

One of the things that Adham brought was a focus on quality. Morhaime recalled that Adham wouldn’t cave to different pressures to get a game done so it could be on a magazine cover or the company could keep to a schedule. That ethic was put to the test early on with The Lost Vikings, a game that Silicon & Synapse built for publisher Interplay. The team felt that the work on the game was pretty much done, and it had been sent over to Fargo, Interplay’s chief.

He made a lot of notes about the game, including feedback such as parts when the levels were too hard or the vikings looked too similar.

“My first reaction was ‘What? It’s fine the way it is,'” Morhaime recalled. “Allen had a very different attitude. He said, ‘He’s right. He’s right about all of this stuff. We took the time and addressed the issues.'”

Silicon & Synapse didn’t have the resources to fix the game, but Fargo freed up some money for Silicon & Synapse to go back to work on the fixes.

“One of the things I fondly remember about Blizzard (Silicon and Synapse at the time) was how they would take a core concept for the game and push it further than what the initial designs called for,” said Fargo, in an email to GamesBeat. “Never would they accept the bare minimum as the bar. And they always accepted comments to improve without being defensive but instead sought out the issues like a scientist would look for more test results.”

Based on Fargo’s feedback, Adham’s team whittled the number of characters in The Lost Vikings in the game from 50 to three.

“We wound up with a much, much better game,” Morhaime said. “Going through that process, and seeing where the game was before, and how much better it became with this additional effort, was a huge lesson to us. We got additional feedback from people who weren’t inside the development team, but knew how to make games. That was incredibly valuable. Addressing that feedback and going through an iterative process, especially toward the end of development, could really move the meter on quality. We have done that on every game since.”

The company would go on to become Blizzard and release 28 games since the Lost Vikings. But the stakes behind those games, and the scale of each effort, have become exponentially higher. For instance, the team that maintains World of Warcraft, the biggest premium online game in the industry, has more than 250 developers. Compare that to the handful that made the original Warcraft real-time strategy game.

That sense of taking pride in the work, meeting the highest quality expectations, and never shipping a game before it was ready was instilled within Blizzard early on, Morhaime said. And it became part of the glue that held the culture and the team together for 25 years, Morhaime said.

“There are a bunch of key moments that reinforced how important quality was,” Morhaime said. “There’s always intense pressure to ship. Early on, Allen was singularly focused on making sure that we fixed the issues with the product and made as good a product as possible. If we knew there were problems, we had to fix them before it released. It wasn’t about missing opportunities, because additional opportunities would always come.”

Making the first Warcraft

When I was at the Los Angeles Times, I interviewed Adham and Morhaime when the company was going by the name Chaos Studios. It was based in Costa Mesa, California, and it had just 19 employees at the time. They had done successful games for Interplay, and were ready to move out on their own.

Adham came off as a natural salesman and leader. His team was hardcore, and they wanted to make games that they wanted to play themselves. They weren’t fans of movie-like titles with very little interaction. The future of games, Adham once told me, was “very interactive, very sweaty-palmed, action-oriented.”

That was appealing to gamers like Chris Metzen, a senior vice president of story and franchise development, who has been at Blizzard for about 23 years. His father told him not to take the job, but Metzen rolled the dice on Blizzard, and it panned out.

He joined it a couple of years after it started, and was employee No. 15. Hired as an animator, he had no formal training in animation. But he jumped into it and did well. The company had become good at making and shipping games in a short time. But it wasn’t necessarily that stable. During those early years, Adham did not take a salary or a vacation.

“At one point, the boss was paying us on his credit card,” Metzen remembered. “We were holding on, doing good work. But the publishers we were looking for were in varying degrees of financial health.”

It wasn’t until a game called Dune II came out on the PC that the team really figured out what it wanted to do. Developed by Las Vegas rival Westwood Studios and published on the PC by Virgin Interactive, Dune II was the first of many games in the “real-time strategy” genre. In the game, based on the Frank Herbert novel Dune, the opposing forces of House Atreides and House Harkonnen fought for control of a resource, spice, on the desert planet of Arrakis. The player controlled the Atreides forces, creating buildings, training troops, collecting spice, and launching attacks, all at the same time. The computer-controlled enemy also did the same thing at the same time, so that the battles took place in real time, with each side simultaneously pushing its forces into battle.

It was fast and furious gaming, the kind that Adham liked to call “sweaty palm” gameplay.

“We saw it and thought, ‘Wow, this is really cool!,” Morhaime recalled. “We got really enamored with real-time strategy. Dune II was just a single-player game. We thought real-time strategy against another person would be really cool and so much fun. We thought we would set it in a fantasy universe because we all loved fantasy.”

Patrick Wyatt, a Silicon & Synapse game designer, recalled how the team played Dune II exhaustively during lunch breaks or after work. Morhaime remembered that the team really wanted to create multiplayer real-time battles. Work began on what would later be called Warcraft.

“Development of the game began without any serious effort to plan the game design, evaluate the technical requirements, build the schedule, or budget for the required staff,” Wyatt wrote many years later. “Not even on a napkin. Back at Blizzard we called this the ‘business plan du jour,’ which was or standard operating methodology.”

Wyatt was initially the sole developer on the project, and he was later joined by some artists.

“Each day I’d build upon the previous efforts in organic fashion. Without schedule milestones or an external driver for the project, I was in the enviable position of choosing which features to build next, which made me incredibly motivated,” he wrote.

By early 1994, he had made enough progress to warrant additional help. He was joined by Morhaime and number of others as the Warcraft project grew in importance.

Creative freedom under Davidson

Silicon & Synapse was acquired for what, in hindsight, looks like a tiny amount of money. Davidson & Associates, an educational software company based nearby in Torrance, California, came calling. The company, which Bob and Jan Davidson started, acquired Chaos Studios in early 1994 for $6.75 million.

“Back then, it seemed like a lot,” Morhaime said.

Indeed, Adham was 27 at the time, and Morhaime was 26. The Davidson deal made them into millionaires. At the time, that was a pretty rare thing for game designers. Of course, today, it’s not unusual to find twentysomethings who are billionaires. Davidson & Associates liked them because they were so young and could target games at their own generation.

“Everyone in our company is really passionate about video games,” said Adham in an interview I did with him during those days. “We are all fanatic game players. We are the target market, and that gives us an advantage in knowing what is going to sell. I watch cartoons Saturday morning … because I like them, not just for a job.”

They chose to sell to Davidson & Associates because it promised creative independence.

They set about renaming the new acquired game studio, since there was a rival in the tech business that also used the Chaos name.

“Boy, we had such a hard time finding a name that everyone liked and wasn’t already registered as a trademark,” Morhaime said. “We went back to the drawing board. Brainstormed. Allen got attached to the name Ogre Studios. But we were already part of Davidson & Associates. Jan Davidson hated the name Ogre. She really didn’t like the way that would sound to her shareholders, who thought they were investing in an educational software company.”

“Can you please pick something else?” Jan Davidson asked.

Midnight Studios was another option. Adham went through the dictionary and came up with Blizzard.

“It’s just a cool-sounding name, I don’t know,” Morhaime said. “I’m really happy we landed on that.”

With the distribution power of Davidson & Associates, Blizzard had enough clout to get Warcraft on store shelves. The game debuted in November, 1994, on the PC in North America as an MS-DOS release. It introduced the fantasy world of Azeroth, with humans squaring off against orcs. Like other RTS games, you built a base and an army, and you destroyed the enemy. It wasn’t played on the Internet. Instead, it was played via direct links via computer modem or via local area networks. It was a huge hit, and it spurred a series of sequels.

Metzen became the writer on Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness. Blizzard made that game with just eight people, and yet it was also a breakout hit when it debuted in 1995. It Blizzard’s first game to hit No. 1 on the sales charts, and it delivered a great experience over the Internet. Blizzard followed at a furious pace, coming out with an expansion pack to Warcraft II in 1996. It got into a fierce war in the RTS market, with rivals such as Westwood, Microsoft, Big Huge Games, and many others.

As the company hit its stride, Metzen did voice acting and did a lot of the script work for future games. He became a Blizzard lifer, and he’s committed to offering fans a heroic experience in vast, compelling worlds.

“It’s remarkably the same over time,” Metzen said. “It’s in our DNA. Even in games like Hearthstone, it’s still pretty heroic. It makes you feel exceptional and effective.”

Blizzard North and the making of Diablo

In 1996, Blizzard made a strategic move. It acquired Condor, a Northern California studio in the Silicon Valley suburb of San Mateo, California. Condor had worked on a Super Nintendo Entertainment System version of Justice League: Task Force for Blizzard. And they got along well enough to combine the companies.

Condor was headed by the brothers Max Schaefer and Erich Schaefer, as well as David Brevik. They were renamed Blizzard North, and nine months after the deal, they launched what would become one of Blizzard’s enduring franchises, Diablo.

Diablo was a fantasy role-playing game with hack-and-slash action. At first, Diablo was a turn-based RPG.

“Originally, Diablo came out of our desire to bring the RPG genre back to the masses,” said Max Schaefer in an email to GamesBeat. “At the time, the RPGs were dense, fussy, and cumbersome, weighed down by their own conventions. Sometimes we just wanted to whack a skeleton and get a cool sword. So we set out with that. The first thing we had onscreen was a guy hitting a skeleton with a sword, and we built from there. We made sure that within a minute of starting the game, you were in the action. We used randomized levels and endless loot to keep you wanting more. We actually started development as an independent studio. Once we were bought by Blizzard and became Blizzard North, we were able to greatly expand the scope of the game and turn it into what it became.”

By this time, Adham had earned the nickname of being “the Velvet Hammer.” He had a gentle, measured, yet forceful means of persuasion, Schaefer said.

“We had sort of a hybrid turn-base real-time scheme, and Allen used the Velvet Hammer to ‘suggest’ we try going full-on real time,” Schaefer said. “At the time we thought that messing with your inventory and skills would be cumbersome in real time, but once we tried it, it was obvious it was the right call.”

Condor also toyed with a different art style at first. The Primal Rage game had just come out, and it used physical models and stop motion animation, also known as Claymation. The Condor team considered using that art style for Diablo. But it turned out to be the wrong approach. Instead, it went with a 3D isometric art style.

The game took more than the initial expected budget, and it had an impact on delaying other games such as StarCraft. But when Diablo debuted in 1996, it was a blockbuster.

Blizzard North created Diablo II, but it was eventually shut down in 2005. But its legacy was enduring, and Blizzard went on to create successful Diablo III game, using a different studio.

“Blizzard was where we learned about professional standards in video game production back in the ’90s, and to this day they still carry the torch,” said Schaefer, who went on to create the indie studio Runic Games and the successful Torchlight series of action-RPGs. “It was an amazing, competitive, supportive, and exciting place to work thanks to dedicated local management, distant and mercifully indifferent corporate ownership, and a deep, unrelenting commitment to quality.”

Under new ownership, again and again

Above: Trailers for Blizzard Entertainment’s World of Warcraft: Cataclysm and StarCraft II play outside the NASDAQ Marketsite after Activision and Blizzard executives celebrated Blizzard’s 20th anniversary by ringing the closing bell, Monday, March 7, 2011 in New York. (Jason DeCrow/AP Images for Blizzard Entertainment)

Blizzard grew into a big powerhouse, beating its competition and outlasting them.

“Blizzard made us work harder at Westwood with each Command & Conquer release,” said Louis Castle, the cofounder of Westwood Studios, maker of Dune II, the Command & Conquer series, and many other RTS games. “Blizzard’s commitment to production quality and excellent RTS mechanics pushed us to do our best. Westwood loved playing Blizzard games. Every new release inspired us to work harder and deeply discuss how we could try to reach the very high bars they set.”

Virgin Interactive acquired Westwood 1992, and Electronic Arts bought it in 1998. But EA shut down Westwood in 2003. That was typical of the creative exhaustion and merger mania that led other companies to fall by the wayside.

In the meantime, Blizzard went through its own corporate gyrations — moves that could have become a catastrophe. In 1996, CUC International, a mail-order club company, bought Davidson & Associates for $1.6 billion, and it also shelled out $1.5 billion to buy game publisher Sierra On-Line. Then CUC merged with HFS, and the company was renamed Cendant. By 1998, CUC got busted for accounting fraud, which took place years before the merger. Cendant stock lost 80 percent of its value over the next six months.

The game business was sold off in 1998 to French publisher Havas. In 1999, French media company Vivendi acquired Havas. Blizzard became part of the Vivendi Games group. Vivendi also acquired Universal, the movie company, in 2000. By that time, Blizzard had 200 employees.

Morhaime realized what sort of leadership path was the best for him to take, as the company became bigger and bigger. Blizzard stayed put under the same ownership structure until Vivendi Games merged with Activision in July 2008 in an $18.9 billion deal. That led to the creation of Activision Blizzard, with Blizzard Entertainment still operating independently with the larger company.

At that time, Blizzard had 2,600 employees. Since that time, Blizzard has been part of Activision Blizzard. Morhaime has continued to run Blizzard independently, but he reports to Activision Blizzard CEO Bobby Kotick. They’ve worked together now for seven years. Activision Blizzard’s value is now $22 billion, and one of its largest shareholders is China’s Tencent, the largest video game company in the world.

StarCraft gets lost in space

During those years of turmoil, Blizzard continued to make outstanding games. One of them was StarCraft, a sci-fi real-time strategy game that became one of the first esports sensations. It was supposed to be a one-year project that came on in 1996. But it didn’t.

The team that made StarCraft experimented with three different game engines. And they concluded that the game should stay in 2D. That was one of the issues that prolonged the games’s release until 1998.

Diablo’s success reset the bar for StarCraft, and the company decided to redesign it with a higher level of quality. Everybody was chasing the success of RTS games: more than 80 were in production at the time StarCraft was in the works.

StarCraft had to be better.

Patrick Wyatt, the former Blizzard designer who also worked on Warcraft, once described StarCraft as a “two-and-a-half-year slog with over a year of crunch time prior to launch.” He wrote, “The game was as buggy as a termite nest. While its predecessors [Warcraft I and II] were far more reliable games than their industry peers, StarCraft crashed frequently enough that playtesting was difficult right up until release, and the game continued to require ongoing patching efforts post-launch.”

Rob Pardo joined Blizzard in 1997, when the whole company was less than 100 employees.

He went to work on StarCraft, which Adham was very closely involved with. Pardo offered advice on balancing the game among the three difference races that fought each other. What struck Pardo as surprising was that Adham, the CEO, was so deeply engaged in the product. They would do play tests together where they discussed just how well the Science Vessel was working under different circumstances.

“We had the CEO of the company testing the ideas in each build,” Pardo said in an interview with me.

Ultimately, StarCraft had a team of 30 working on it. The team had time to polish the gameplay. When it came out a couple of years late, nobody cared about the delay. StarCraft became a phenomenon. It sold millions of copies, and it kicked off the competitive esports leagues in places such as South Korea, where it went on to become a national pastime.

The success of Diablo and StarCraft created a kind of flywheel effect.

“With Diablo and StarCraft, [Blizzard] felt much bigger than we anticipated it would be,” Pearce said. “Diablo was the first Battle.net game. The original StarCraft was where we first started seeing the emergence of a global player community and the birth of esports. Both of those games were out within 18 months of each other, and they had a huge impact on what we were doing and who we were doing it for. With those games, we all of a sudden had a massive online global community.”

One of the lessons: Pardo said that for every game that followed, the team always tried to have a playable prototype up as often as possible for the team to iterate upon.

World of Warcraft slaughters the competition

The first mention of World of Warcraft was in the fall of 2001. But it had already been in development for some time. Pardo was the lead designer, and Adham, as always, was closely involved in the development.

“It was a fairly simple idea,” Pardo said in an interview with me. “There were a lot of us who were fans of the MMO genre. During StarCraft, a lot of us played Ultima Online, Dark Age of Camelot, and EverQuest. It wasn’t a big leap to imagine a Warcraft-themed MMO. We though there was an opportunity, because MMOs were fun but not accessible.”

The game was going to be an online virtual world, a place where Warcraft fans could gather and interact with each other and go on quests. It was Blizzard’s answer to Sony’s massively multiplayer online game, Everquest, and EA’s Ultima Online.

The huge success of Warcraft as a single-player or 1-on-1 game set off huge interest in a full online world, said Mike Vorhaus, president of Magid Advisors, and one of the advisers for Blizzard over time.

Adham himself took charge of it. He was joined by veterans like Metzen, Sam Didier, Tom Chilton, and Rob Pardo. They filled the world with beautiful places, tons of characters from different races, and many quests for players to embark upon. It was a huge undertaking. By the time World of Warcraft shipped, the team had grown to 60 people, and Blizzard itself had 500 employees.

When the game launched in 2004, many felt it had been overhyped. Yet each year, it grew. Pardo felt good as he saw guilds in other games move over en masse to World of Warcraft. By August, 2005, World of Warcraft hit 4 million subscribers. That prompted Blizzard to throw its first BlizzCon fan event in Anaheim, Calif.

Blizzard didn’t sit still. It had to feed the beast, making new content. It would launch new content regularly. In 2007, the company debuted World of Warcraft: The Burning Crusade. That expansion featured flying mounts. To put them in the game, the company had go back and redo huge parts of the older lands, since the developers wanted the game to look good no matter where you were flying over it, Pardo recalled.

“That was a lot of work for the artists,” Pardo said. “But they did it.”

In 2011, the game had a peak of 12 million paying subscribers, with more than $1.2 billion in revenue generated from subscriptions.

“I don’t think anyone understood how massive World of Warcraft would be,” Pardo said. “It impact everything, like customer service, servers, and game design. We knew it was a good game. We thought it was the best MMO. But the biggest MMO at the time was 500,000 subscribers. We thought we could get a million. I don’t think any rational person would have predicted the size of WoW.”

Indeed, with a growing customer service division, the popularity of World of Warcraft would finally drive Blizzard’s employee base into the thousands.

“It was a very exciting time,” Pardo said. “We brought fresh people into the studio.”

The game succeeded in part because it was accessible and had a great tutorial. It leverage the massive base of Warcraft fans. And it actually demanded less time than some of its rivals. It also had a way to get players on board in new markets such as China, which eventually became its biggest market. Blizzard regularly followed it up with huge expansions that made the World of Warcraft bigger — and even more compelling to players.

“We always approach our games as if we were making them for everyone. We want anybody to sit down and play a Blizzard game. We apply that to everything. That’s part of our values: easy to learn, difficult to master,” Morhaime said. “Having something that is easy to learn doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have depth. You don’t have to throw all of the depth at the player when they first sit down.”

Five years ago, author Jane McGonigal said gamers have collectively played about 5.93 million years of WoW. Its community put in about 30 million hours a day. It became the MMO to beat, and it killed off many competitors.

“We saw in the research consumer intention that would drive WoW way beyond Everquest or anyone other MMO, ever,” Vorhaus said. “In fact, World of Warcraft did great, another example of the quality of games made by Blizzard. What Magid didn’t see, and what has been hugely exceptional, is that many, many years that World of Warcraft grew and even now, is holding its own.”

The game is finally starting to lose its grip on its audience. But today, a dozen years after its launch, World of Warcraft has more than 5.5 million paying subscribers. The team still has 250 employees working on new content.

But eventually, Blizzard will transition to a new cash cow.

“Regardless of development, sales, and marketing gambles, Blizzard created one of the most successful video game franchises the world has ever seen,” said Ted Pollak, analyst at Jon Peddie Research and head of EE Fund Management. “World of Warcraft could be called the ‘Led Zeppelin of video game franchises.”

A change in leadership

By early 2004, Adham was pretty sure that World of Warcraft was in good shape. And on January 16, 2004, about 10 years after he started Blizzard with Morhaime and Pearce, Adham resigned.

He attributed the departure to the accumulated effects of working long hours and doing the crunch routine for many years. He decided to pursue a new career in finance, and said he would continue to remain a consultant for Blizzard. Adham started running his own hedge fund.

To Pardo, Adham’s departure wasn’t a total surprise. After StarCraft shipped, Adham took off on a months-long sabbatical to recharge.

“He always pushed himself real hard in the home stretch,” Pardo said. “He always had some challenges with working too hard. He was getting burnt out in the process. He also wanted to pursue things other than games in his life.”

The hedge fund made sense in part because Adham was still engaged in game theory, or trying to compete against the bets that others were making on investments.

Morhaime, who became CEO of Blizzard, said that Adham lived up to his statement about offering advice. To Morhaime, it enabled a much smoother transition in the leadership.

For many years, Morhaime had taken a less public role, and Adham had been the public face of Blizzard.

“It was more of a transition where it changed my role,” Morhaime said. “I became the main point of contact with our parent company and with the sales organization at our parent company. For several years after Allen’s departure, I was still involved in development. There was a point where I had to give up programming. I definitely miss those programming days.”

Canceling big games

In all of Blizzard’s history, Morhaime has had eight different bosses. But he didn’t really let that affect the game studio. If Blizzard dealt with any drama, it was self-imposed.

During its history, Blizzard has canceled at least 10 games. These include Nomad, Raiko, Warcraft Adventures, Games People Play, Crixa, Shattered Nations, Pax Imperia, Denizen, StarCraft: Ghost, and Titan.

Blizzard games have some humor, but they usually focus on a sense of epic gravity. And when Blizzard somehow steered off that course, it didn’t hesitate to stop and start over. Warcraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans was one of the ill-fated games. It was a black comedy, and it was timed to come out about the same time as Grim Fandango, a LucasArts game by adventure-game virtuoso and funny man Tim Schafer in 1998. Morhaime said all the LucasArts adventure games were so good that Blizzard’s wouldn’t have been able to compete.

“It’s hard for me to explain,” Metzen said. “In a weird way, we are like a giant, giant rock band. We work together and we pull together. If we stumble, or have blown it, or are forced to cancel a game, it’s because we aren’t feeling it. It’s not the end of the universe. We are a strong team. We pull together, and we hit it out of the park on the next one. Sometimes they are deeply rattling. But our people take a longer view of why they are here.

“In every instance I know of, it is a collective decision” to end a game, Metzen said. “[Morhaime] is very encouraging of us when we get to those points where we are past the point of no return. He’s always been very supportive of our decision-making in that way.”

StarCraft: Ghost was an example of a game that became a huge project before it was canceled. It was a third-person shooter version of StarCraft that started out under development by Nihilistic Software. Blizzard announced it in September 2002, as a console title, and it would be an embarrassment.

That project went off the rails, and Swingin’ Ape Studios took over development in 2004. Blizzard bought that company. But it canceled the GameCube version of the game in 2005, and then it announced in March 2006 that StarCraft: Ghost was on “indefinite hold.” It was labeled “vaporware,” and Morhaime didn’t actually say that the game was canceled until 2014. It wasn’t a complete waste, as Blizzard published a novel, StarCraft: Ghost — Nova, with the backstory of the game’s main character.

Blizzard said that the success of World of Warcraft and the development of StarCraft II commanded a lot of the company’s resources, and Ghost went to the backburner for good.

“It’s better to focus on things that make an impact,” Morhaime said in an interview with me a few years ago during the Dice Summit game industry event. Asked if anybody cried when the games were canceled, Morhaime replied, “Somebody cries. It’s painful. A lot of work gets thrown away.”

Pardo added, “It’s always emotional and a very difficult decision to do something like that. It’s much more about the fact that a team of game developers have put their hearts and souls into it. And you have to make the decision. I would say in every case it was the right decision, and more often it should have happened sooner. We knew fans would be upset. But those cancellations solidified the Blizzard reputation.”

These days, it’s very expensive to cancel a game. Titan, a sci-fi work that was going to be Blizzard’s next great massively multiplayer online game, was canceled in 2013. At the time, Titan had a team of 100 developers. It was similar to a game being overseen by Blizzard’s sister company, Activision, which was working with Bungie on Destiny. At first, Blizzard reduced the staff by 70 employees. And then it finally canned the rest of the game.

Titan was critical in some ways, as it was supposed to pick up subscribers as World of Warcraft declined. But titles like Destiny looked like they were going to be better than Titan, and so it fell by the wayside. The common thread? The focus on quality, and the need to put more resources behind games to ensure that quality, is what leads to cancellations. Morhaime said the risk of cancellation is always possible, but he’s got a lot of confidence in the teams he put in place.

“I’m actually very satisfied with the progress we have made in the last few yeas in scaling up the organization of the business, leveling up the leadership for the franchises, so they can focus on operating and developing content for each of those games,” Morhaime said. “I think we’re in pretty good shape and I’m very excited about 2016. I think the games we are working on are excellent. But it’s not going to get easier as we release more games. It will get more complicated.”

Overwatch and beyond

As the stakes got higher and the competition went digital, Blizzard adapted as well. It launched card battler Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft, which generated ongoing free-to-play revenues and has become one of the top games in the esports and streaming community. It debuted Heroes of the Storm, another free-to-play title in the “hero brawler” genre. It is working on Overwatch, a new first-person shooter that is aiming for a mass audience. Seven million people have signed up for the Overwatch beta test.

And it is hoping that the Warcraft movie takes off. That film debuts in June.

“That’s been a long time in the making, and it’s finally here,” Morhaime said.

As the paid subscription business model for World of Warcraft has waned, Blizzard evolved to other embrace business models. With Heroes of the Storm, not only did Blizzard embrace the MOBA genre popularized by Riot Games’ League of Legends (which, ironically, came back from a Warcraft III mod, Defense of the Ancients), it also embraced the free-to-play business model. It ran with that further with Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft.

“None of us would have predicted or seen the success they had, but they deserve it all,” said Fargo, who has gone a different direction with his InExile Entertainment, which thriving independent studio thanks in part to crowdfunding. “They remain unchanged as decent people. What I think was and is most important about Blizzard is that they are students of the marketplace. Anyone can be creative but analyzing openings in the market and knowing which points to hit is a real skill.”

“It’s not about trying to retain people in our community so we can reap the financial reward for it,” Pearce said. “We want to see the work that we do enjoyed by as many people as possible.”

Blizzard is now producing things at a much bigger scale, supporting more games, platforms, and regions than ever before.

“Five years ago, when we launched StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty, we were just operating World of Warcraft,” Morhaime said. “Now we are operating six games that are all generating regular content to our players. We’ll have multiple releases this year. Just being able to do all of this stuff simultaneously, at a Blizzard quality level, is not easy.”

In addition to Adham, some senior people have left Blizzard. Pardo, who rose to the rank of chief creative officer, left Blizzard in 2014 after 17 years.

“I had taken a sabbatical of a few months off,” Pardo said. “Once I had time to reflect, it seemed more like it was the time to change.”

Morhaime said that he believes that Blizzard has lasted as long as it has because of the commitment to quality. The team really enjoys going out to meet real players at the company’s BlizzCon events in Anaheim every year. Many designers and developers also engage with fans on social media. Morhaime doesn’t want to let Blizzard fans down.

“The biggest key is having a shared commitment to quality,” he said. “We are all trying to do the same thing, providing the best experience possible for our players. When you focus on that, and achieve that, people have such a sense of accomplishment. That’s what keeps us going.”

As to why he still stays at Blizzard, 25 years after it began, Pearce said, “We’ve still got a ton of stuff to do.”

As for what he wants to see out of the game industry right now, Morhaime went in an unexpected direction: kindness.

“I think that right now, people still aren’t very nice to each other online. If we can help make the interactions between folks online safer and more friendly, that would make it all more fun and gratifying for everyone.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More