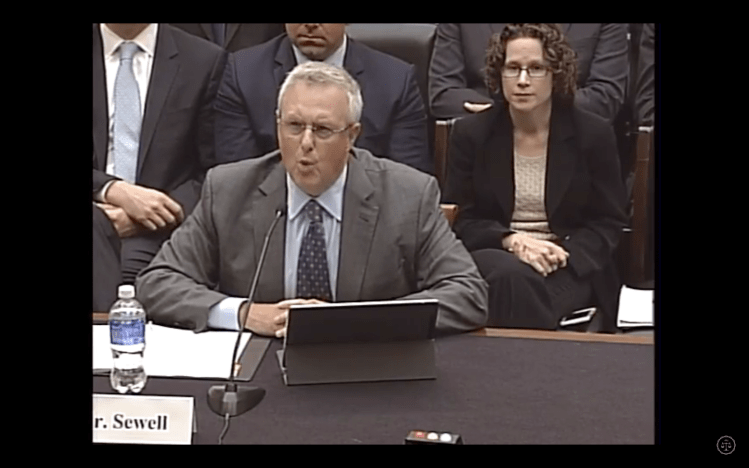

Today, Apple sent its general counsel and senior vice president, Bruce Sewell, to Washington, D.C., to speak before the House Judiciary Committee about the ongoing battle the company is waging against the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) over the encryption of San Bernardino shooter Syed Rizwan Farook’s iPhone.

The event had all the markings of a forced meeting between Silicon Valley and federal officials. There were some Apple supporters, like professor Susan Landau of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute, who was testifying alongside Sewell, and Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.). There were some opponents, like New York County District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., also testifying, and Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wisc.). And then there were some U.S. representatives who simply didn’t seem to understand all the dimensions of the case.

Sewell, not surprisingly, stuck to most of Apple’s talking points, like the importance of public safety for end users of its devices and the notion that building the software the FBI wants would amount to the creation of a backdoor into iPhones. But at the end of the hearing, a new idea did become clear.

When it comes to new legislation, unlike the FBI, Apple does not seem to know what exactly it wants to propose to Congress — even though the company has expressed previously that it would prefer for the conversation about this controversy to be held in public with Congress rather than behind closed doors in court.

“Can you submit legislation … that you could wholeheartedly support and lobby for that resolves this conundrum between [Apple] and the bureau?” Rep. Trey Gowdy (R-SC) asked Sewell.

“I firmly believe we could draft legislation,” Sewell said. “I don’t have it for you.”

Gowdy suggested that an “army of government relations” people would have issues with anything that Congress, left to itself, would come up with, and so he wanted to know if Apple could possible come forth with a starter of sorts that would be less likely to end up stalling.

“If, after we have a debate to determine what the right balance is, then that’s a natural outcome,” Sewell said.

Gowdy asked when that would happen.

“I can’t anticipate that, Congressman,” Sewell responded.

That Apple didn’t come to Washington with specific policy in hand seemed to irk Sensenbrenner as well.

“All you have been doing is saying, ‘No, no, no, no,'” he said.

Sensenbrenner was right. Legislation is what matters to Congress. It’s the currency of that branch of government. Apple has been engaging with the DOJ lawyers on the judicial front, and Apple CEO Tim Cook has previously met with President Barack Obama and plans to meet with him again. When it comes to policy, though, Apple has some work to do.

‘My blood boils’

Sewell was inevitably asked what he thought about the argument that not cooperating with the FBI’s request amounted to a “marketing strategy.”

“Every time I hear this, my blood boils,” he told committee chairman Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.). “This is not a marketing issue.” He stated that Apple doesn’t spend its money on ads that talk up its products’ security or encryption.

If anything, Sewell said, Apple is opposing the FBI’s demands because it is “the right thing to do.”

Where in the world is NSA?

Some of Apple’s best arguments came from the person to Sewell’s right on the panel: Landau. A former Google and Sun employee, Landau reminded the committee of the reported lack of data sharing between the FBI and the National Security Agency (NSA) in the 2000s. Though that situation involved cross-agency collaboration, she noted that the problem at the core of the issue seems to be alive and well.

When she had given a briefing to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the past, Landau said she had learned that NSA, too, had certain skills that it “won’t share with the FBI, except in exceptional circumstances.”

Ultimately, Landau concluded, the U.S. government was using “very much a 20th century way of looking at a 21st century problem.”

Brittney Mills

Of course, the hearing also afforded supporters of the FBI’s position an opportunity to make their case, as they pushed for the creation of an “FBiOS” entry into Farook’s phone. As the hearing was in Washington, it kept to the political tradition of citing cases of individual victims.

Rep. Cedric Richmond (D-La.) brought up Brittney Mills, a woman in Baton Rouge, La. who was shot dead last year. Local law enforcement officials have suggested that Mills’ locked iPhone 5 could have clues to help them figure out who killed her. The district attorney in the case was on site for today’s hearing, along with members of Mills family, Richmond said. In that context, Richmond asked Sewell if he would “have a problem” with brute force attacks on a phone in order to get at certain information. Sewell said that would amount to a security vulnerability, so yes, he would.

Richmond went on to ask if Apple currently has the technology to unlock Mills’ iPhone, or knew anyone who does.

“Short of creating something new, no,” Sewell said.

Written testimony from Sewell, Landau, Vance, and FBI director James Comey is here.

For a full overview of the Apple-FBI case, check out our timeline.