Full disclosure: Gamestop Corporation provided the review copy of Call of Duty: Black Ops, free of charge.

The tragic events of September 11, 2001 had an immeasurable impact on America. Beyond the expected political reposturing, the country suffered a noticeable change in its cultural vocabulary. While the Bush administration curried military support in national addresses, Hollywood and the TV industry followed suit with more patriotic, nationalistic content.

Partly intentionally, but chiefly unconsciously, developers have inundated the industry with titles that glorify international violence and canonize soldiers. Though I hate to admit it, the sheer number of modern shooters leads me to believe that we all work and participate in an industry that no longer questions violence and rarely attempts to justify it.

The latest in a recent slew of modern shooters, Call of Duty: Black Ops attempts to neutralize one of America's most controversial wars, Vietnam. While the franchise has typically maintained a small anti-war element, Treyarch has jettisoned any and all peacable tendencies of the Call of Duty series.

Black Ops and its ilk are beginning to influence the way we learn about violence and war. As stories that promote violence as a solution to conflict continue to bombard gamers, it's become difficult ignore the obvious pro-military angle of these first-person shooters.

As any proud gamer would, you're probably ready to defend these games as balanced and educational. Relax and hear me out : Who knows? You might find yourself agreeing with me by the end.

In 1998, the band Rage Against the Machine warned us of the "thin line between entertainment and war." In fact, Zack de la Rocha, the group's vocalist, predicted a post-9/11 partnership between popular culture and global militarization. Did he have it right? Well, click on the image below, and take a look at this recent TV spot for Black Ops:

"There's a soldier in all of us." This sounds deceptively similar to a recruitment slogan, doesn't it? Oddly enough, most developers aren't shy about their close collaboration with the U.S. military. In fact, Medal of Honor creator Danger Close boasted about the help their studio received from the Marine Corps during development. Hell, games like America's Army openly admit their purpose as recruitment tools! Maybe we don't need conspiracy theories to explain why people like playing military games. Gamers like guns and violence, and the military has plenty of that. What's worrisome isn't the cause, but the effect of games like Call of Duty: Black Ops.

Whatever skepticism academics have, it's abundantly clear that video games have adopted an important role in directing American culture. Among adolescents and children, the multi-billion dollar industry is more relevant as a pedagogic device than literature, film, and possibly even television. After all, which influenced your understanding of World War II more: Call of Duty or that history book you browsed through in sixth grade?

Considering the size of the franchise's audience, Call of Duty games have some responsibility to provide an accurate, unflattering depiction of war. And yet, what does Black Ops teach the people who play it?

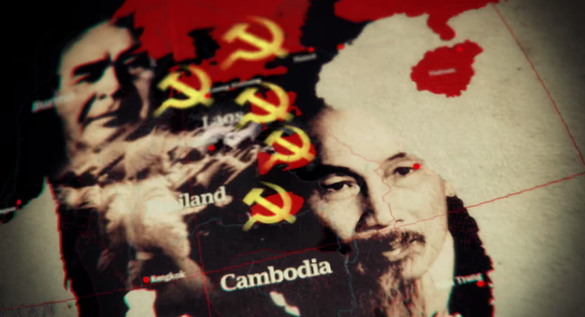

Stop the dominoes from falling. Vietnam is the key!

Though Black Ops blatantly lifts scenes and lines from cinema classics like Full Metal Jacket and The Deer Hunter, it fails to communicate the same anti-war message that Kubrick and Cimino did. Despite Treyarch's attempts to paint war as a grim, ugly business, the quality of the voice acting and animation fall startlingly short. The result are over-acted, melodramatic cinematics, which immediately conclude with the unapologetic massacre of Viet Cong regulars.

One of the successes of Modern Warfare's narrative was the way in which Infinity Ward portrayed war as confusing, futile, and tragic. The player works against the extremists and aggressors of a fictional Arab country in order to maintain peace, not to destabilize it. Black Ops begins with the assassination of a real-world political figure. Talk about getting straight to the point.

A hallmark of the Call of Duty franchise has always been the "quote screen." After dying in campaign mode, the player's vision blurs to reveal a quote. These lines were almost always decidedly anti-military. Harnessing the wit of philosophers and diplomats like Aeschylus and Colin Powell, the games reinforced the sad reality of war. Apparently, Treyarch wouldn't stand for that kind of liberal, pinko thinking and removed the quote screen from Black Ops.

Weirdest of all is the way in which Treyarch rewrites the history of the Cold War. Whereas prior installments quoted some of President Kennedy's most peaceful speeches, the former president adopts a hawkish philosophy and even sends the player on an assassination mission in Call of Duty: Black Ops. Kennedy's wasn't the only history redrafted, however.

With all the facts hindsight provides, academics generally agree that America's attack on Vietnam was illegal and illegitimate. Black Ops challenges the cultural memory of Vietnam by exaggerating the brutality of the enemy and the nobility of its protagonists. As if to bring attention to the Iraq War, Treyarch edits the history of the Vietnam War to include a narrative of Russia developing WMDs with the Vietcong, thus justifying the entire operation.

Create the Peace Corps, will you? Take that!

I'm not espousing that Black Ops should abandon violence altogether. I'm of the opinion that self-conscious violence, provided the correct context, is perfectly fun and sometimes even healthy. But context is what's key: Other military shooters qualify the violence they portray with the caveat that war is inadvisable and pointless. At the very least, if other video games celebrate war, the developers are usually parodying something. Unfortunately, Black Ops flirts eerily close to the line between mindless fun and propagandist media.

Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman, a former Army psychologist, recently revealed standard training techniques which use video games to teach soldiers how to kill without fear, anguish, or hesitation. The use of modern video games by the army is proof of their effects.

Will Call of Duty: Black Ops influence you enough to sign up for military service? Probably not. But I'm becoming awfully tired with games that portray enemy combatants as savages, downplay the effects of war, and glorify the army.

In her book Militarism and Video Games, Nina Huntemann writes, “Since 9/11, there has been an interesting trend in the kinds of games released. What I find really frightening is that in our playtime, in our leisure time, we’re engaging in fictional conflicts that are based on a terrorist threat and never asking questions."

Take Ms. Huntemann's advice and ask questions.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More