This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

It might well be presumptious of me to call myself a 'Dev', as though I have a string of successful indie games under my belt and a legion of adoring fans hammering the 'donate' button. Dream-chasing can be arduous and unrewarding, and working in the video games industry is one of the longest and most treacherous career paths around. I've finished a game or two, sure, but no-one's paying to see my next one.

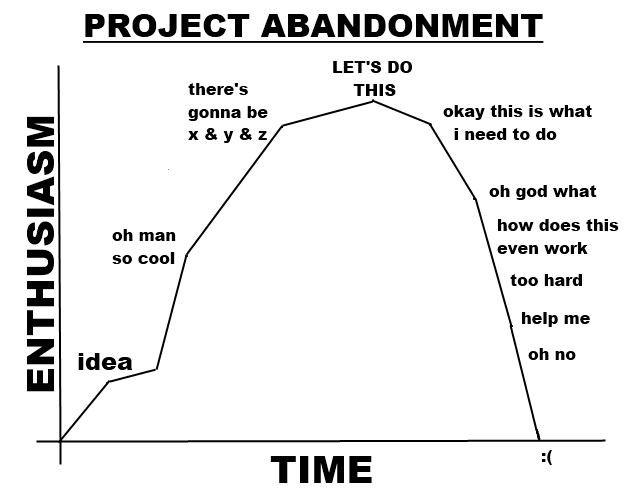

Many of you will be familiar with game development's learning curve. It's rare to meet someone with an interest in video games who hasn't thought about making their own at one point or another. I'm sure this rigorously scientific graph will strike a chord with a fair few people:

It's all too easy to be discouraged by the seemingly effortless success of others at an immensely complex and difficult task. The long, drawn-out nature of game making means that many people lose motivation and fall apart before the finish line. Most devs start out because there was one game they played that stuck in their mind – one game that made them realise just how much the medium can achieve. Half-Life, Dwarf Fortress and Mega Man are some popular examples. If there's an idea in your head; a yet-to-exist game you want to play or a personal story you want to tell, then I would like to share something with you: the game that I look to whenever I feel like it's pointless to continue.

I would never have played Cave Story if a friend of mine hadn't bought me a copy of the Steam re-release as a present. He hadn't played it (he knew almost nothing about it), it just struck him as something I might like. I'd heard about it in passing a couple of times, but never thought much of it. The official description on the website read:

Cave Story is a jumping-and-shooting action game.

Explore the caves until you reach the ending.

You can also save your game and continue from where you left off.

With hindsight; a description so utterly inadequate as to be ridiculous. I would go so far as to name it the greatest misdirection in the history of gaming. Pixel demands that you go into the game expecting nothing more than an action-oriented platformer, a fun diversion. Cave Story requires no hype, no trailers, no interviews and no introduction. It is the perfect example of a game that is entirely self-contained, bringing you everything it has to offer – a deep and involving story, emotional investment in your actions and a viscerally beautiful experience in both sight and sound – using nothing but the tools of the medium.

The problem in writing this article is that the sheer quality exhibited by each and every aspect of Cave Story's design is overwhelming. I cannot write about it in the way I wish to, since my incoherent babble would only make sense to those who have played it. It's like trying to eat a mouthful of the perfect trifle in the perfect way – you'll never fit every layer between those cruel human jaws without tarnishing the overall experience of such a deep and well-engineered dessert. The only way I can think of to convey the value of this game is to break it down like any other into its arbitrarily-decided component parts and explaining why they work so well, but even then I will fail to explain properly. Really, the best thing you can do is to go – now – and play it through in its entirety. Twice, I'm afraid. Otherwise my description (lurid and flowery though it may be), will be just as laughably inadequate as the three lines Pixel used to describe it.

Once you've done that, I would like to speak to you over the page.

Feel

Cave Story comfortably sits alongside a small number of games that are mechanistically perfect. From a select few NES classics through to some expertly-crafted modern titles, these are games that do not separate you from your avatar in any noticeable way. The lack of this quality is easily identified by complaints of mouse lag, broken immersion or awkward camera controls. It doesn't take much to jar a player out of their experience, and a great many games that are otherwise excellent have been foiled in this area. When you distill this quality down to its purest form, it can be called Feel. Cave Story has been tuned so that every movement you make, from the smallest nudge of the player character through to the most complex evasive maneuvers, just Feels right.

Put simply, Feel is the difference between seeing a game:

And playing a game:

Excellent fanart courtesy of http://vicewolf.deviantart.com/

Weapons start off feeling capable, but clumsy. As you advance, growing in power and skill, they grow right alongside you until they feel incredibly powerful. In moments of desperation (of which there are many), firing a single shot from a levelled-up Polar Star can feel more satisfying than the world-destroying endgame megaguns of lesser games. Sound effects and impact visuals that are just right make the game world feel truly reactive. This is what I mean when I talk about visceral beauty – something so well made that your body can't tell the difference between games and reality anymore. No amount of fully physically-simulated girders in games like Red Faction: Guerilla can satisfy this need more elegantly than strong artistic design. Kinect will fail, Move will fail and any kind of fingerquoted "Virtual Reality" will fail because they are cheap tricks. Incredibly expensive and advanced, but cheap tricks nonetheless. No amount of technological wizardry can serve as a substitute for Feel.

Emotion

There will be spoilers in this segment, but they cannot be helped. I could never forgive myself if someone missed out on one of the most harrowing moments in gaming because I felt the need to wax lyrical about it, so please do not continue if you haven't played the game.

There is a moment, about two-thirds of the way through the game, where you are made to feel crippling amounts of guilt. Almost all players will experience the same thing on their first playthrough (assuming they do not use a guide), thanks to seemingly obvious choices afforded the player up to this point. This means that something awful will happen for your sake, and you will be powerless to undo it or repair the damage. The lead-up to this moment is so perfectly crafted that I can honestly think of no better example of how to use the medium (any suggestions in the comments will be greatly appreciated).

The battle ends. The music stops. The enemies vanish and you are left alone, underwater, with an unresponsive character. You know there must be some way out, because the game has never presented you with an unfair challenge yet. Every death was your fault and yours alone, so you continually bested the game over and over, growing in skill, confidence and power, until you reached this juncture. The numbers tick down alarmingly fast as you frantically search for an escape, praying you won't have to repeat the difficult battle you just finished. None of this makes sense, and gamer's panic sets in as you drop to single digits.

Fade to black.

Your fault.

Cave Story is challenging. One playthrough should have been enough. There's no logical reason to play through the entire game again just to see a different ending. The restrictive save points stop you from just reverting and trying to see all the different possibilities, so you should just give up and play something else. Logic. It's the same cheap lengthening tactic used by a lot of RPG's to make you replay their games again and again to see hidden content. Right? Logically, we should just take the ending we got and appreciate the story we experienced on its own merit.

No.

The true, genius idea at the heart of the game's design revolves around one moment. One single moment that made you feel. A character you never appreciated is gone forever. The powerful, energetic, fearsome warrior who ran with you to the death without looking back, hesitating or faltering in your relentless charge to the Core. Logic dictates you should leave her and enjoy the story as it was, but Cave Story outright challenges you. It challenges your preconceptions about games, stories and established canon. Cave Story throws down the gauntlet with a picture of her body in the credits, and few choice words near the endgame, hinting that you have the power to change things. You, the player. Cave Story stands over you and addresses you directly.

New Game.

So you do it. You plough through the game a second time, now acutely aware that the game is watching you. Monitoring your progress. Choices that seemed clear the first time around now take on new significance. You hang on to every line of dialogue and charge through boss battles with renewed determination. You go through the moment again and emerge defiant, dragging Curly from the clutches of the story and blazing your own revised canon all the way through to the hellish finale.

Cave Story engages the player in every way it is possible for a game to engage a player. You are invited to defy tropes that have been around since the medium's inception. The perfect Feel and the powerful Emotion work in concert to show you just how deep you can be involved in the game's world. It exemplifies everything that is laudable about games, and tackles everything that is despicable about them. Cave Story isn't about a story about a cave. It's a game about games. It's about what games are, what they can be and why you should care. It is the soul of the author and his greatest work.

This is the benchmark by which all games should be judged, and I don't even need to tell you why. I just spent two pages trying, and I still didn't capture it adequately. Cave Story's greatest strength is this: everything there is to know and think and feel about it is conveyed naturally to the player. Everything you need to know about Cave Story is right there in the game. The three-line introduction isn't just a comic aside: it is literally the most you can say without encroaching on the game's territory. I don't even know why I'm writing this! My point would have been perfectly made just by getting you to play it.

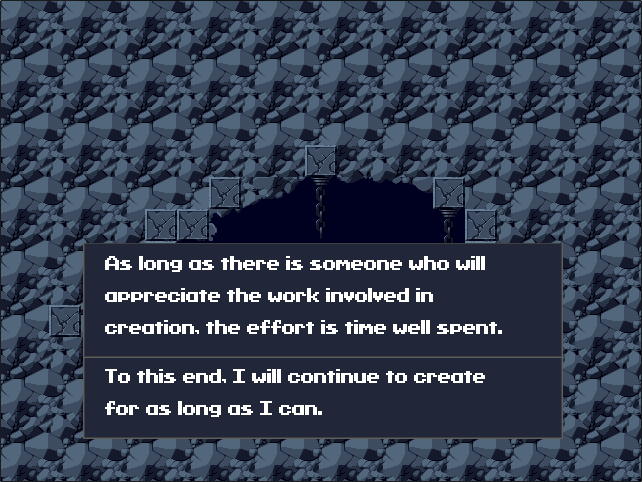

I mentioned earlier that I make games. This piece is called Cave Story: A Dev's Perspective. I wanted to share one more thing about it: why it encourages me to continue. There is a piece of dialogue near the endgame, easily missed or misinterpreted, that speaks to me on an unsettlingly deep level. An old gunsmith tells you in passing how he feels about the relationship between the wielder of a gun and the person who crafted it. He talks about how he has always been aware of the connection, but never experienced it before. Until now. Until you. He offers you his heartfelt thanks, and afterwards has only this to say:

Thank you, Pixel.