This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

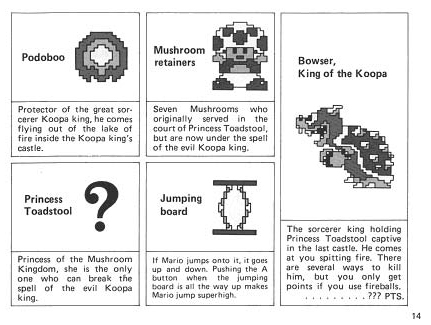

Did you know Bowser, King of the Koopas, is actually an evil sorceror?

It's true. At least, it's true according to the original instruction manual for Super Mario Bros. on the NES.

Earlier this week, EA Sports announced that it would no longer ship paper manuals with its games, furnishing digital copies in-game instead. Reasons for doing so include making packaging more environmentally friendly as well as saving on printing costs.

Those are logical, understandable points. But you know what? I don't give a crap. I want my paper manuals. Because they proved that, even in a bottom-line industry like gaming, publishers cared (at least a little) about showing off the creativity of the people who made the game.

Now? I'm not so sure.

Back in the day, games were so simple that the instruction manual was the only way to get across the story. And did they ever. The aforementioned booklet for Super Mario Bros. informed you that you weren't just crushing bricks and stomping turtles for fun — those bricks were actually transformed Mushroom Kingdom citizens! So every time Mario punches a block, that's an innocent Toadling he's killing? Reading the manual gave gameplay an entirely different flavor.

The Legend of Zelda's manual went even further — it included cartoon drawings that gave a whole new perspective to the top-down, pixelated action on the screen. Along the way, the booklet gave hints and tips that were a lot more helpful than "It's dangerous to go alone." As I read, I could sense the feelings and artistic motifs the developers were trying to convey. I don't think I'd have gotten that picture so clearly without those few simple pages.

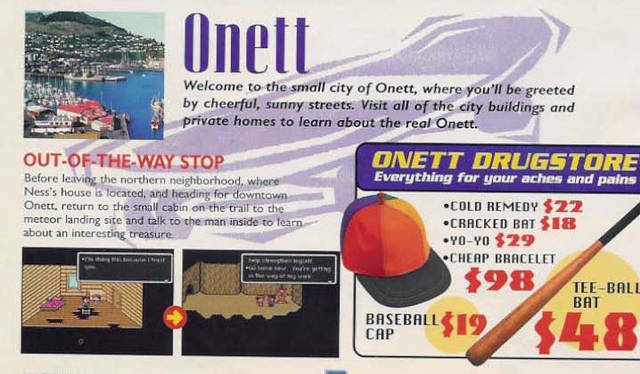

The SNES version of Earthbound didn't just have a manual; it came with an entire strategy guide, chock-full of adorable artwork and background detail. In fact, the book read like a tourist brochure, highlighting all the areas you'd pass through in the game as if you were just seeing the sights. I can't imagine any company providing something so charming these days.

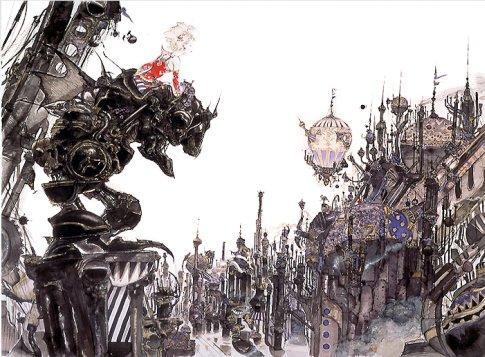

I also remember the booklet for Final Fantasy 6 (then called 3) on SNES, specifically because of its artwork. FF3 used super-deformed sprites for its characters, so you never really got a sense of what they looked like, aside from a small portrait in the menu screen. But the FF6 manual included the full concept drawings for each party member, so you could see how the artists envisioned them before transferring that vision to pixelated form. (This was how I first discovered the work of Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano, whose manga and anime I came to enjoy later in life.)

These constructions of paper and staples gave depth and color to the games they described. They conveyed creativity in ways the titles themselves could not.

These days, things are different. We have tutorials to teach us how to play. We have vast compendiums of backstory and lore that we can access on the fly (see also: Final Fantasy 13). And games don't have to rely on — indeed, they shouldn't rely on — the written word to get the story across. Advanced graphics and gameplay help to do that already.

Plus, you'll find a lot of that concept art and background detail in the strategy guides that companies like Prima and Brady Games pump out. Why bother packing a high-quality item like that Earthbound book in with the game when you can sell it later for 20 bucks?

So I understand why instruction manuals are going extinct. But I never saw them as mere objects that taught me which button to press. I saw them as another part of each game — another avenue of creative expression for the developers to explore.

And if that avenue closes in the name of saving a few bucks, or even saving the planet, I for one will be disappointed.