This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Editor's note: While I'm proud to have been a Mac owner since the computers running HyperCard at my junior high school blew me away, I've always been disappointed by the state of gaming on the Mac. Richard's insightful and in-depth history of Mac gaming sheds light on why I — and most other Mac-owning gamers — feel that way. -Brett

The Mac isn't exactly known for its ability to play games. And given the repeated snubbing from big publishers and developers in recent years, you can easily understand why. But the Mac hasn't always been a wasteland for games, sparsely populated by a handful of the PC's sloppy seconds. Over the course of three articles, I will discuss the highs and lows of Mac gaming. In this first article, I'll look at the history of Mac gaming. In future articles, I'll look closely at the current situation and try to predict the future of gaming on the Mac.

The Early Days

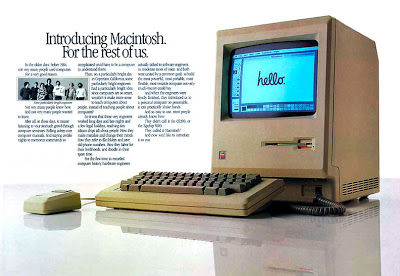

In January 1984 Apple released the revolutionary Macintosh 128k computer, which featured an operating system that used a graphical user interface (GUI) instead of the command-line interface found in other personal computers at the time. The Macintosh's monochrome display and limited RAM restricted its potential as a games machine, and Apple instead marketed it as a productivity machine — they were very careful to avoid having the Macintosh labeled a "toy." The closest thing to a game available for the first Macintosh was a desk accessory called Puzzle.

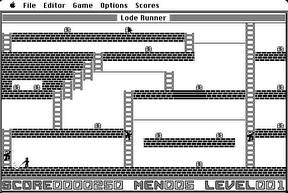

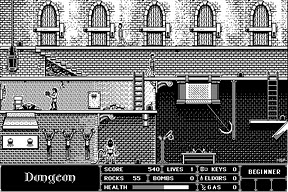

But it wouldn't be a computer if it didn't have games, and entertainment software soon emerged on the system. Text adventures and Apple Lisa ports came almost immediately, with Lode Runner — ported from the Apple II in 1984 — hot on their heels. Highlights in 1985 included Chris Crawford's seminal work Balance of Power and a port of Wizardry, while the brilliant Dark Castle came a year later, amidst a growing number of ports and original titles.

However, the Macintosh simply wasn't built for the fast, exciting, and colorful games being made for other platforms — although technically it was capable (except for that whole "color" thing). It was designed to be a productivity machine best suited to the emerging desktop publishing field. So Mac gamers would miss out on many high-profile arcade ports and other commercial twitch-based games. Instead they got slower-paced adventure, strategy, and role-playing games. LucasArts and Sierra graphical adventures, Ultima- and Wizardry-style RPGs, and Will Wright's Sim games all found a strong audience.

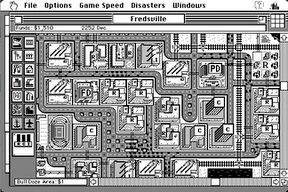

Still, impressive original titles continued to emerge. A number of notable Mac-first games came out in 1987, including Scarab of Ra, The Fool's Errand, Beyond Dark Castle, and Crystal Quest, which was the first Mac game that could be played in color. More original titles and games visually superior to their PC cousins were released in the finals years of the 1980s, including an impressive port of SimCity, first-person action game The Colony, and fan-favorites Shufflepuck Café and Glider. Together with some top-notch ports of popular Apple II games, these titles helped to soften the blow of the Mac being a low priority with many leading developers and publishers.

Struggling Against the Competition

The Mac received its share of multi-platform releases, but Mac gamers often had to wait months to years for the big titles to make their way over. And it only got worse as the Apple II lessened in popularity. Rather than migrate to the Apple II's more advanced cousin (the Macintosh), developers flocked to the Amiga, Atari ST, and IBM PC, with its new Windows operating system.

It didn't take long for Macs to get color monitors and higher-resolution graphics, but by then Windows — with its vast array of cheap (and customizable) IBM-compatible hardware options — had gained a very strong advantage in market share. This made it difficult for Mac gamers to be taken seriously: No matter how boisterous they were in preaching the merits of their favorite platform, they couldn't argue with the numbers. There weren't enough people using Macs to make it a worthwhile target platform for all but the niche genres already proven on the Mac. Worse still, the Mac had to compete with cheaper machines designed and marketed with games in mind, such as the Atari ST and Amiga, and the rejuvenated console market, which included the Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Master System.

From Stackware to Killer App

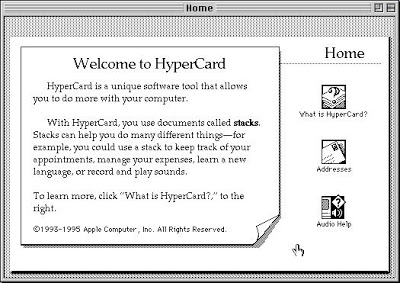

One application — bundled with all Macs from 1987 onwards — soon opened the door to a new kind of gaming experience. HyperCard was branded as an all-purpose software platform, with a simple-yet-powerful programming/creation interface built upon the idea of hypertext, later popularized by the Internet. It allowed for the easy creation of interactive multimedia applications, complete with sounds, animations, graphics, and user input. Its use of "cards" and "stacks" made HyperCard perfect for games that used a static background (e.g. adventure and simple arcade-style games). Software created using HyperCard was typically shared on bulletin board systems and Usenet, although there were also some disk releases for more commercial or polished applications. Notable HyperCard games include Cosmic Osmo, The Manhole, and Spelunx, all of which were created by Rand and Robyn Miller, who would go on to make Myst.

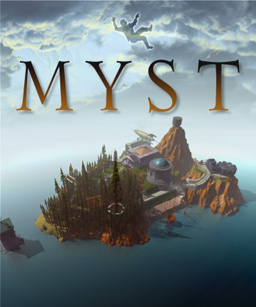

Building on their HyperCard experience, the Miller brothers released Myst on CD-ROM in 1993. The game cast players as the lone explorer of a lavishly detailed but apparently deserted island of the same name. Critics praised Myst for its graphics, mature story, and engrossing experience, but derided (especially in later years) it for its obtuse puzzle design and lack of characterization and interaction. Many consider Myst the beginning of the end of the adventure game genre, mostly due to the huge number of clones and sequels, none of which overcame the original game's shortcomings.

On its way to becoming the highest-selling game of the 1990s, Myst changed the video game landscape. Games immediately started coming out on CD, with better graphics, movie cutscenes, better sound, and voiced characters. But despite first appearing on the mac, the majority of sales came from the Windows version — released two years later. Worse, the Mac shared little of the consequential boon to the computer games market, for Apple was spiralling into financial crisis — attributable to some poor business decisions, the rise of Windows, and a horribly confusing product line.

Dark Days Ahead

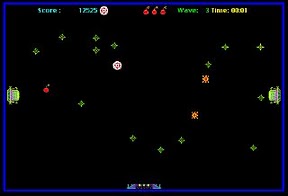

Were it not for signs of mismanagement at Apple, gamers likely thought bright days were ahead for Mac gaming. In a rare twist, SimCity 2000 (Maxis and Will Wright's 1993 follow-up to the original SimCity) was developed on a Mac and then ported to Windows. Bungie proved their talent and commitment to the Mac with Marathon in 1994. The same year, Ambrosia Software was founded, following the success of a highly-polished Asteroids clone called Maelstrom. Spiderweb Software and Freeverse Software were also founded in 1994, releasing one-man-team projects Exile and Hearts Deluxe, respectively. Meanwhile, in-house porting teams at Brøderbund, Infogrames (MacSoft), Microsoft, and Interplay (MacPlay) ensured that most big Windows titles would be ported quickly.

Between three talented new shareware developers, support from big publishers, and a growing number of games made on a Mac, the Mac looked like a healthy platform. But the rosy picture wasn't destined to last.

Game Over

Microsoft released Windows 95 to ridiculous levels of hype in August 1995, touting "new" and revolutionary features long present in Amiga and Mac operating systems. Mac sales fell while PC sales rose, further increasing the divide between installed bases. Apple had no answer. They tried licensing hardware-clones (too late in the game) and hurriedly put together a major upgrade (later canceled) to their operating system. Between mismanagement, poor finances, and retreating momentum Apple simply could not compete with Microsoft.

The Mac was never a particularly strong gaming platform, but these falling sales ensured it would not be considered by any except a few die-hard developers and publishers of games. Unfortunately for those companies, retailers began refusing to stock Mac software and games, citing low sales per square inch of shelf-space (compared to Windows 95 products). Thus began a vicious feedback cycle of declining sales leading to fewer orders, which in turn brought fewer sales (and so on). It took its toll Mac game companies. On April 29, 1998, MacPlay (by far the biggest Mac game publisher at the time) announced its closure by parent company Interplay.

Commentators and analysts wrote Apple off; market share was shrinking, the Mac operating system was outdated, and the company was bleeding money. The Mac was dead…or so they thought.

The Messiah Returns

Steve Jobs became interim CEO of Apple on July 9, 1997, having returned to the company as part of its purchase of NeXT in December the previous year. He immediately set about restructuring Apple to make it profitable again. Announced on May 6, 1998, the iMac (along with a new partnership with Microsoft) signified the return of Apple to mainstream culture. Market share continued to decline (albeit at a slower pace), but the company now had a chance of survival if its latest attempt at a major operating system rewrite could succeed. (Spoiler: it did.)

In the meantime, though, Mac gamers had slim-pickings. GameSpot lists just 28 Mac games released in 1998 and 37 in 1999 — consisting mainly of "edutainment" software and ports of PC games released one or two years earlier. Undoubtedly, some games released for Mac in those years eluded GameSpot's list. But a few missing games mean nothing in the face of GameSpot's listing of 479 PC games released in 1998 and 543 in 1999. And despite the huge discrepancy in number of released titles, Mac games — whether port or original — continued to manage only an ever-shrinking fraction of the sales achieved by their PC counterparts.

While the iMac revitalized the Mac as a computer platform, it didn't do much for the Mac as a games machine. Even though the colorful new hardware was powerful enough to run the latest games, the installed base was much too low to justify continued support from the big publishers. The Mac gaming scene now consisted of little more than a few Mac-only publishers and porting companies, a half dozen successful shareware companies, cross-platform support from Blizzard, and Bungie (the popular independent developer of the Myth and Marathon games).

Then the tides began to shift. Finding a good (relatively) new game on the Mac became somewhat easier when MacPlay was revived in 2000 by United Developers LLC. They ported a flurry of Interplay games before becoming a software retail outlet in 2004. Other porting companies were also in relatively good health at the turn of the millennium, with Feral, Aspyr, and MacSoft all growing during this period. Apple even convinced id Software to release the Mac version of Quake 3 alongside the Windows version. And they promised to improve support for games technology. For a while, people believed them.

Bungie first announced Halo at MacWorld 1999. The game promised to be a third-person action/adventure for simultaneous Mac and Windows release that would prove the Mac's capacity for hardcore gaming. It wasn't to be, however, as Microsoft bought Bungie in 2000, and the game was released for Xbox in 2001 redesigned as a first-person shooter. The game eventually came out on Mac in December 2003, but that did little to remove the bitter taste in the mouths of many Mac gamers. One of the most successful, long-running, and dedicated developers of original Mac games had defected to the competition.

OS X Arrives

The long-awaited overhaul of the dated Mac OS came out in March 2001. Dubbed Mac OS X, it brought the necessary features of a modern operating system while dropping much of the baggage of its 17-year-old predecessor. It kept support for Mac OS 9 software through the "Classic" environment (essentially, a software abstraction layer) and the Carbon API. For OS 9 games, as with other applications, compatibility with Classic was pretty hit-or-miss, with a majority of recent software working and a good chunk of older software not. Of course, that wasn't much of an issue until hardware revisions some years later dropped support for booting into Classic, by which time only a few die-hards still cared.

The changes brought by OS X were hugely significant for Apple's future and the operating system's functionality, but they had little immediate benefit to gamers. If anything, the arrival of OS X was bad for Mac gaming in the short term. Some games were not compatible with OS X without an update. Others required longer development time to ensure compatibility with both OS 9 and X.

On the other hand, the long term benefits were considerable. Apple improved support for OpenGL and Java, in addition to updating or introducing a number of other frameworks useful in game development. Then there's the addition of other features (such as memory protection and pre-emptive multitasking), which benefited games more indirectly by improving the stability and performance of the operating system.

Of course, what really matters to games is potential audience. Sales continued to rise as Apple improved their public image and brand exposure, thanks largely to the instant-hit iPod (also released in 2001). But it was generally business as usual for the Mac games industry, with a handful of developers releasing a steady trickle of games, most of which were old news for Windows or console gamers.

With market share creeping up and the Internet enabling a better distribution channel, Mac game development became slightly more profitable every year. Then Apple through a spanner in the works.

New Beginnings: The Intel Transition

The switch to Intel architecture was met with mixed response by the Mac gaming community, far more so than previous transitions from 68k to PowerPC and from OS 9 to OS X. Some heralded the move as the savior of Mac games, as multi-platform development and porting to the Mac would be much easier — and cheaper — for developers of Windows games. This would soon be supported by the announcement that TransGaming had developed a wrapper technology, which would reduce porting time dramatically, with nothing more than some tweaking to Cider (the translation layer) required.

But others called it the final death-knell of Mac games. You could run Windows on a Mac, they argued, so why would companies bother to make Mac versions of their games? Perhaps the greatest fear of these doomsayers was that the few remaining Mac-focused developers would either run out of business or jump ship and later stop supporting the Mac — a precedent set and upheld sadly too many times by the likes of Cyan, Bungie, and Maxis.

Porting companies, among the few surviving bastions of Mac game development, feared the worst. Rather than make the turnaround for Windows ports faster, they expected a marked increase in development time, as they would initially need to support both PowerPC and Intel processors. Even when looking ahead a few years to when they could drop PowerPC support, the reduction in porting time was expected to be insignificant.

The crux of the problem was that Mac ports of Windows software tended to be slower, buggier, less-supported, missing features, partially incompatible with the PC version for mods or online play, or released months or years later — sometimes even all of the above. This was partly due to the fact that some popular middleware technologies were Windows-only, which meant that ports of games built with these tools had to use hacks and workarounds, or else drop key features. Worse still, in some areas it could be extremely difficult to find the Mac versions of popular games, which sometimes weren't available even in Apple stores. When you could find them, they were often more expensive.

Uncertain Times

These days, you can finally run Windows on the Mac at full speed. The one big reason not to buy a Mac has been removed. Fans of the Mac operating system or Mac-only applications who need Windows for one reason or another can now have the best of both worlds, running the two systems side-by-side on the same machine. And it appears a lot of people were waiting for this possibility. Sales have risen markedly, especially for portable Mac systems.

Stay tuned for Part 2 (found here), which will look at the commercial games of the Intel Mac era and the impact of this transition on the Mac gaming landscape. You can also catch the final instalment, Endlessly Waiting For Tomorrow, which looks ahead to the future of gaming on the Mac.

Originally published at MacScene.