Despite having the world’s third largest economy, Japan’s social media ecosystem is perhaps the most unique in the developed world — and among the most difficult for Silicon Valley to understand, let alone capitalize on.

It’s a semi-enclosed greenhouse where Facebook flounders behind Twitter, and where LINE, a social network dominated by cartoonish stamps, rules. So with help from my local colleagues here in Tokyo, here’s the latest user data on Japan’s leading social networks, expressed in five key takeaways everyone in the Valley should know:

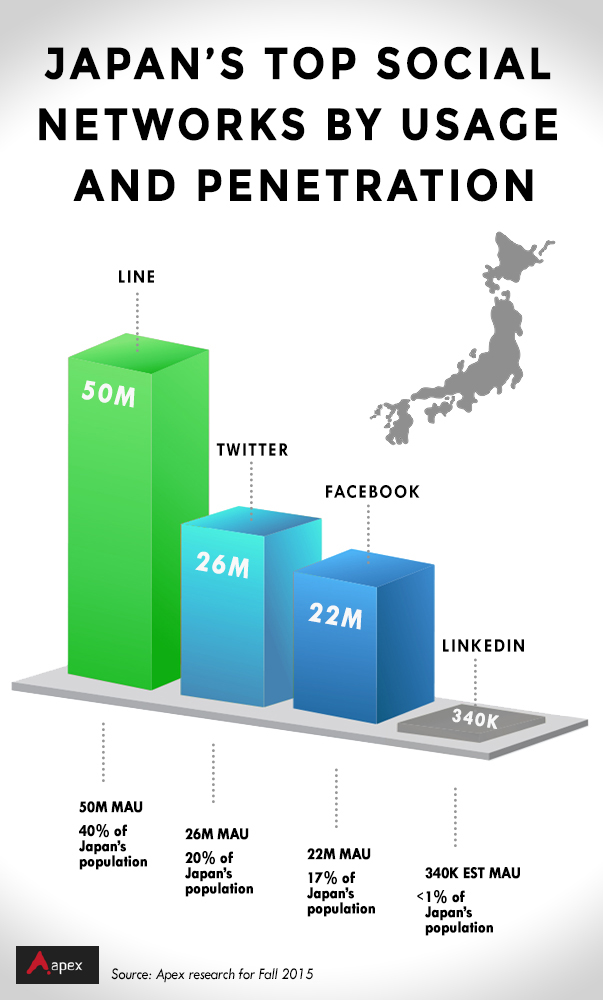

1. LINE is the Facebook (and the Uber and Apple Pay) of Japan

With about 40 percent of Japan’s entire population using it every month, LINE is the undisputed leader. Launched in 2011, the mobile social messaging system first launched in response (so the typical explanation goes) to the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that year. The disaster ravaged Japan’s phones and cellular networks, but left much of Internet connectivity intact, prompting NHN Japan employees to quickly prototype and release LINE as an alternate communication platform. LINE’s ascendance is also attributable to Japan’s telecoms, which make their customers pay for SMSes, and charge smartphone callers up to a dollar a minute. LINE’s Skype-like VOIP chat, by contrast, is free.

Not only the default messaging app of Japan, LINE also rolled out a number of product features no one else had, like stamps — basically, high-resolution and high-concept emojiis. While the app is free to use, the stamps are bought as in-app purchases, and remain the company’s core revenue stream, forecast to earn it over $800 million this year alone (it earned $247 million in Q3 2015 according to the recent earnings report). LINE is expanding beyond stamps however, having recently added an Apple Pay-like service, a Spotify competitor, and an Uber-ish taxi feature.

2. Facebook is the LinkedIn of Japan

After some early stumbles, Facebook is finally getting traction in Japan and is now used by about 17 percent of the entire population, primarily by people in their teens and twenties and by Japanese who live/travel overseas. However, Facebook in Japan is not the Facebook we in the West are used to, due in great part to Japanese culture, which frowns on public expressions that may seem boastful (for example, posting selfies from a beach on Maui). Facebook’s insistence on real-name-only accounts makes Japanese even more reluctant to express personal opinions on the social network.

Consequently, Japanese are much more likely to treat Facebook as their professional face, emphasizing their work experience and business connections — like LinkedIn. For that reason, it’s not uncommon for Westerners to get random friend requests from young Japanese users whose photos depict them in sober business clothes. They’re not actually seeking friendships per se, they’re networking.

Speaking of LinkedIn, there’s bad news for that network in Japan:

3. Locals are eating LinkedIn’s lunch

LinkedIn currently has 1.36 million registered users in Japan. Assuming 25 percent are active (probably a generous estimate), that’s less than 1 percent of the total population. Why has LinkedIn failed to succeed in Japan, where by contrast, it’s doing relatively well in China? That’s largely due to some stumbles at launch here: It took the company some 2-3 years to get fully localized for Japan. Even now, it’s impossible to send in-mail messages that allow users to add the “san” honorific to the addressee’s last name — terribly bad form, culturally, especially in a business context. At the same time, local competitors have aggressively attacked Japan’s market for business social networks: Bizreach in Japan has over 400 employees, Wantedly about 50. LinkedIn, by contrast, has around 10 staffers.

4. As Twitter can tell you, it is partnerships, not virality, that grow users

With 26 million monthly active users (some 20 percent of the total population), Twitter is the largest Western social network in Japan. However, that comes after years of struggle against a local competitor, Mixi, which also offered a pseudonym-based microblogging network. The equation changed, however, when Twitter partnered with Joi Ito’s Digital Garage, which ran Twitter’s Japanese operations for a number of years.

There’s a larger lesson for Silicon Valley here: Companies cannot expect to gain the kind of viral growth that’s commonplace in the West, but instead must focus their energies on partnerships. In Japan, “growth hacking” isn’t about adding viral hooks to your product — it’s about old fashioned biz dev and partnerships, which often require beer and karaoke to seal the deal. As another example, mobile gaming company GREE only saw massive growth after partnering with a phone carrier that put GREE’s products on its homepage.

5. Social networks rise & fall (and rise again) in popularity

I mentioned Twitter’s struggles against local competitor Mixi, and there’s an ironic coda to that: Once dominant in Japan, Mixi’s lead was rapidly chipped away at by Facebook and LINE, while it also struggled with its mobile strategy. As a social network, Mixi now barely exists (the company no longer discloses user numbers). Mixi the game developer, however, still thrives: Monster Strike, its action-RPG game, became an enormous success, earning an estimated $4 million dollars a day. GREE, which once had a popular social network attached to its games, is now developing (some would argue cloning) popular apps, while another fallen network, DeNA, recently partnered with Nintendo.

This rise and fall of social networks is broadly applicable to the Japanese consumer market, which is intensely trend driven and often fickle, fiercely embracing a product one month and then suddenly rejecting it the next. Consequently, it’s often difficult for companies to maintain their staying power without being constantly ready to change course.

Final advice

While Japan may seem like a closed market to Western tech companies and startups, we are also seeing more and more overlap, especially on the social media front: Twitter is more popular in Japan than in the US, and messaging service LINE is also popular in America, with the company reporting 25 million U.S.-based users, especially among Asian-Americans. A number of Western companies are already using LINE to promote their brands, such as Coca-Cola, which is selling polar bear Coke stamps in LINE, and Disney, which has seen massive success for its Tsum Tsum game after forming a partnership with the social network.

This is not to say there aren’t risks. We see that with the failure of LinkedIn, which fell short by using a strategy that wasn’t agile or architected for the culture. But as we saw with Mixi, a failing company can also reinvent itself from disaster, suddenly redeemed by Japan’s enthusiastic (if faddish) culture. The underlying lesson is one Twitter finally learned the hard way: Find a local partner who can work with you, and don’t try to close that partnership on Skype.

Ken Charles is the founder of the Tech Industry team at Apex, a Tokyo-based market entry and strategic partner for Western companies in Japan.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More