[Editor’s note: This is an opinion piece by Jeremy Liew, a parter at Lightspeed Venture Partners]

One of the hallmarks of the last few years on the internet has been the growing length of the “long tail”. Compete released some data last year showing that its panel was visiting 77% more websites than it did five years ago:

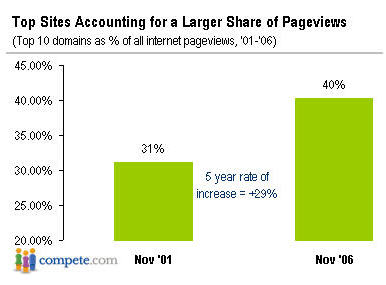

Interestingly enough, Compete also released data showing that the “head” of the internet was growing in size:

Interestingly enough, Compete also released data showing that the “head” of the internet was growing in size:

Together, this suggests that there are now many new sites getting only moderate traffic. While these sites may never grow big enough to become public companies, they are very likely getting to a scale where they can break even. I spoke on this topic at the web 2.0 expo where my presentation analyzed how big sites needed to get to hit both of these goals.

GROWING NEED FOR AD NETWORKS

Many of the smaller ad supported sites turn to ad networks for monetization. This trend is being matched by advertisers embracing the channel. A recent report by Collective Media found that:

* 66% of advertisers plan to increase their usage of ad networks in 2007

* 88% of respondents planning to use online ad networks in 2007 (up from 77% in 2006).

* 57% of respondents believed how an ad network targets audiences was the #1 differentiating factor between networks

* Reach (the number of people that will see an ad) (at 52%) and Efficiency(the average cost to achieve your Reach) (at 66%) were still the key drivers for why agencies/advertisers include ad networks on the buy.

However, not all ad networks are created equal. With such a glut of ad inventory on the market, it matters a lot how an ad network targets an ad – as seen above its the #1 differentiating factor between networks.

To understand why this is, let me first give some context on ad sales. As a guy who has “carried a bag” myself, I believe that sales cycles are directly proportional to the complexity of the sales message, and RPMs(Revenue per thousand page views) inversely proportional.

A simple sales message results in a short sales cycle and high RPMs. Take automotive advertising; imagine you’re selling online advertising to Toyota.

Autoblog has the next easiest sales proposition. Autoblog has amassed an audience of auto enthusiasts. While they may not all be in-market car buyers, they have a natural affinity to cars, and selling ads against this vertically targeted audience is a relatively simple proposition with relatively high RPMs.

The Washington Post sells its demographic. It argues that its readership skews higher income and hence is more likely to buy a Lexus. It’s a pitch that has worked in print and on TV for years, and works online as well, although not quite as well. Sales cycles will be reasonable, and RPMs lower than for Autoblog.

Large sites such as Myspace sell reach. The pitch goes something like “Lots of people visit us, and some of them might want to buy a car, right?” It’s a tougher sale, and even when successful, it generally results in CPC campaigns that mitigate the advertiser’s risk, often resulting in low effective RPMs.

Obviously then, some of the biggest beneficiaries of these trends have been the content specific ad networks, such as a network full of Autoblogs.. Hence a smaller level of overall traffic scale is needed to get to high revenues. At AOL, the channels with endemic advertisers such as automotive or travel always got the highest CPMs and sell through rates, and content specific ad networks are essentially creating what I call synthetic channels.

SYNTHETIC CHANNELS

Synthetic channels,ad networks comprised solely of sites focused on a single topic, are like the channels on the big portals. They have an advantage in brand building. By guaranteeing that all sites in their network are about a single topic, they can aggregate a critical mass in traffic while still enjoying endemic site RPMs. This is, in a sense, a “hack” to true contextual targeting, but it has the advantage of being simple to understand and hence simple to sell to advertisers.

One example is Jumpstart, a synthetic channel reaching 5m UU/month and focused on the auto industry. It was bought by Hachette Filipacche (publisher of Car & Driver and Road & Track) in April of this year for up to $110m.

Another example is Glam, which started life as an site focused on fashion, but quickly morphed itself into a synthetic channel focused on “Women: Fashion and Lifestyle” and reaching over 12m UU/month. It claims to be the “fastest growing web property in 2007“.

A third example is the Health Central Network, a synthetic channel focused on medical information and tools. Many of Health Central Network’s sites are actually owned and operated by the company as it rolled up small health content sites during the internet bust.

Active Athlete Media is another startup synthetic channel, focused on participatory sports, that was recently covered on Techcrunch.

I think we’ll see more synthetic channels emerge, focused on the high ad spend categories:

BEHAVIORAL TARGETING

Unfortunately, many websites are not targeted enough to be in a synthetic channel. They are untargeted, and as such, are likely to be sold at a deep discount as “run of site” or “remnant” inventory, if they are sold at all.

However, even these sites can still benefit from a lift in RPMs from an ad network that has even some websites in their portfolio that support endemic advertisers. This is where ad networks who apply behavioral targeting can really have a big impact. A large network can anonymously track a user as they move around the internet, recognizing them to be the same person when they show up at different sites across the network. They then use this data to target ads more effectively on “lower value” sites, thereby increasing the value of the ad inventory. So for example, a user who had previously visited Autoblog gets a Lexus ad when they show up on a MySpace page, even though the Myspace page has nothing to do with cars. This has become standard procedure at many of the big networks.

The WSJ recently had an excellent article on behavioral targeting that detailed Pepsi’s launch of Aquafina Alive,their new low cal vitamin enhanced water. The campaign was backed by an online campaign through Tacoda and targeted to people who had previously visited “healthy lifestyles” websites.

The result? Pepsi recorded a threefold increase in the number of people clicking on its Aquafina Alive ads compared with previous campaigns. “We’ve never been able to get to this level of granularity,” says John Vail, director of the interactive marketing group at Pepsi-Cola North America.

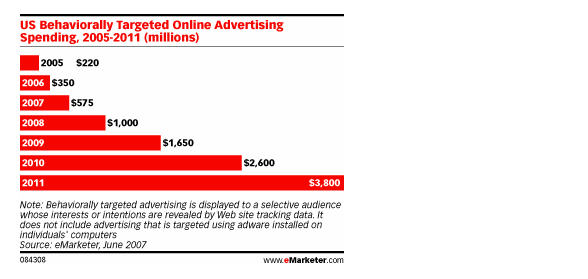

Brand advertisers like Pepsi (you’re not buying the water online after all!) having this sort of success is a strong indicator of the growing importance of ad networks. Pepsi isn’t the only one that this is working for. eMarketer predicts that behavioral targeting will increase by 7x over the next four years.

The key question is how does the incremental value (the increased CPM between the Lexus ad and a “run of network” ad) get split between the three constituents in the relationship; Autoblog, MySpace and the network. This is partly the outcome of supply and demand. Because of the massive surplus of “broad reach” inventory online, the bulk of the value goes to the network and Autoblog.

The network gains disproportionate value from having Autoblog in its network because it can now make a lot of its “broad reach” inventory more valuable. However, in a world with multiple networks, a site that ads “behavioral information” to a network can take that data advantage with it to any other network.

So sites with the opportunity for endemic advertisers have an advantage, not just as standalone sites, or in synthetic channels, but also as members of ad networks. It’s a good time to be a targeted content site.

PEERING INTO A MURKY CRYSTAL BALL

Its interesting to compare the synthetic channel model for ad networks to the behavioral targeting model.

Several large synthetic channels already exist, including iVillage (a synthetic women’s channel) and CNet (a synthetic technology channel). iVillage was bought by NBC for $600m in 2006) and CNet is public with a $1.3bn market cap. The synthetic channel model is close to how media buyers are used to buying advertising today. As a result, they have a much shorter term path to meaningful revenues. We can expect to see some of the newer synthetic channels rapidly ramp up to a scale where they can start to consider lucrative sale or IPO.

Behavioral targeting, on the other hand, is still not as widely understood by the ad buying community. The big brand advertisers are still experimenting with the technology; the fact that Pepsi launched a campaign with Tacoda is still newsworthy whereas Ford buying advertising on Autoblog is not. There is likely a longer path before behavioral targeting ad networks become a standard buy for most advertisers. However, the size of the prize here is enormous. The bulk of online page views are not well monetized today because they can’t be well targeted. Behavioral targeting promises to transform the value of this inventory, lifting its effectiveness and its price.

Because of the strong networks effects of behavioral targeting (the more vertical sites and the more broad reach sites you have, the better your ability to target), and the size of the opportunity, I would expect there to be substantial consolidation in this market. Look for the portals and social networks, both of whom have a lot of broad reach inventory, to make acquisitions in this area.