I remember it as though it were just months ago, but it was early 2005 when a heated discussion rippled across our company. A new way to develop software had matured and had been growing fast since 2001: the agile software development approach. We knew that it would disrupt the very controlled way CI&T had been developing custom software for big companies for over 6 years, and that was scary.

Until then, we were exclusively implementing a formal process called RUP (rational unified process), a successful implementation of the ideas from the unified process framework. In our pitch we were purposely fighting the waterfall method that had been eroding the reputation of software houses over time. Studies were consistently showing that more than 65 percent of big software projects would fail.

Today, it comes without a single sign of pain to say that 100 percent of our projects are carried out using agile, but during that time we were uncertain about the future. That pristine CMMI level 5 certification we had conquered with so much effort over the years was, after all, going to be irrelevant for the industry. Not to mention the detailed processes we had built to align teams and clients in very well defined tasks and waves of work, would all be compromised by a novelty we would need to learn how to use from scratch.

But as clients were demanding us to use it, we found ourselves in a Matrix-like situation where we had no option but to take the red pill.

And then in 2006, we delivered our first 100 percent agile project. It wasn’t all peaches and cream. We struggled to let go of things RUP had taughted us over the years. But nothing resists positive reinforcement, and soon after we would have reinvented the way we build software to fully embrace the agile manifesto.

Enterprises are a rough terrain for whatever new ideas may increase uncertainty, even if in favor of better potential outcomes. We admit that at the beginning we took the manifesto too literally. We had become some sort of fundamentalists who wanted to rigidly follow and implement the philosophy by pushing it down our clients’ throats.

But as we grew from hundreds of employees to half a thousand and later to more than a thousand, and our projects were large scale software implementations for Fortune 100 companies, reality started to wake us up. We realized we were fooling ourselves to believe that we could follow the manifesto so literally. We were more “fragile” than “agile” and we knew we needed to carefully take into consideration the enterprise scale and constraints. The challenge was how to make information and decision making processes work in an environment where it is just impossible to have all stakeholders in the daily meetings.

Let’s take a look at each of the contrasts made in the manifesto, which state that “while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more”:

1. Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

There’s an intrinsic beauty in allowing self-sufficient teams to get their hands dirty to develop the user stories by collaborating with a few key stakeholders like a product owner. While this is great for small teams or start-ups, inside enterprises, a lack of alignment in different levels often generates more heat than results.

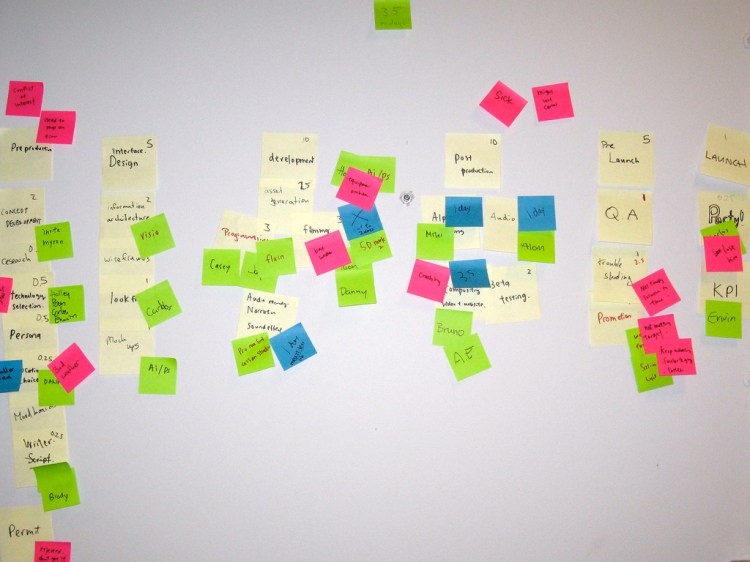

As a colleague of mine recently wrote, we have a more holistic view on the “people over process” piece and extend the concept of teams to different areas of the enterprise so that we can achieve a common ground before and during a project. And there are very simple tools that don’t cost any money that will help teams to communicate efficiently.

We also found out that user experience design as part of the development process is a great way to align expectations with business areas.

2. Working software over comprehensive documentation

Some people don’t realize how profound this mindset change has been to software development. While start-ups do it intuitively, since they have to minimize their costs to get products and services to the market, inside established enterprises a mold of irrational attachment to documentation had to be broken.

There are, however, cases where comprehensive documentation might be necessary — like in highly regulated financial services. If taken too literally, a radical agilist might despise any documentation, which might make the use and proliferation of APIs, to give a simple example, impossible.

3. Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Individuals in big enterprises attuned to the new pace of technology are on board with different contract models where they (and their organizations) can accommodate changes in scope.

Enterprises, however, cannot afford to have zero visibility about deadlines and the productivity of agile teams.

Some agile extremists fiercely fight to disprove any attempt to measure performance of agile teams. But how can one improve on what’s not being measured? And most importantly, how is it possible to adapt to the fast changing pace of technology without adapting processes?

4. Responding to change over following a plan

Companies small and big see a lot of value in having a software development team quickly responding to change without hours of deep discussions. Changes, after all, have become more common and more decisive to project success.

It’s clear, however, that big companies need a plan to accommodate changes, otherwise they will quite often run out of budget. Value engineering has proved to be of tremendously effective tool to help with this.

If you ever heard one or more of the following phrases from agile developers, ask yourself if you aren’t dealing with an agile fundamentalist:

- “Software development is a form of art and thus can’t be measured.”

- “The feature will be ready when it’s ready. Projections from management won’t help, we are working on adding value as quickly as possible.”

- “Productivity measurements and metrics are things of the past, from the mass production processes. Artifacts used by managers to squeeze life out of developers.”

- “The measurement of productivity is a risk because the teams will find a way to artificially prove that they are productive.”

- “We can’t do a fixed price project because we won’t be able to accommodate changes.”

Those are all myths that can be proven wrong.

Metrics can be used to measure processes, not people, and productivity should be collected and monitored by the teams themselves. A team that is not capable of measuring its own performance and understanding what’s affecting it will never be able to promote continuous improvement.

As we found out when we grew to over 1,200 people (we are now at 1,700), the lean principles offer the best set of philosophical baselines and tools for the best implementation of agile, be it with SCRUM, Kanban or anything else.

“Lean” was the key for us to overcome the agile manifesto pitfalls and to be able to scale that approach inside big companies like Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Coca-Cola, to name a few.

We are now a smart collection of “lean agile enterprise” evangelists, as opposed to agile fundamentalists, and our clients are happy with that, reporting quality and throughput performances never before seen.

Our organization isn’t the only one who’s noticed this phenomenon. Dave Thomas, one of the founders of the Agile Manifesto, recently wrote a blog post to suggest the term “agile” should be dropped.

In my opinion, we just need to discern between evangelists and fundamentalists.

Márcio “Mars” Cyrillo is executive director at CI&T, creator of smart applications that add a layer of intelligence to business. He is currently responsible for global marketing operations, the global partnership with Google and CI&T’s strategic early involvement with the emergent market of smart applications (CI&T Digital Brain). With CI&T since 1999, Mars holds a PhD in applied physics from Universidade Estadual de Campinas and two MBAs in sales management and entrepreneurship from Fundacao Getulio Vargas and Babson College. Mars is driven by constant improvement in: technology, his running, and the best lens to capture the NYC skyline.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=56af0c0d-6f77-4452-8622-e7d4fcfdc1f3)