The decline of Research in Motion‘s Blackberry smartphone, reflected in the resignations tonight of co-CEOs Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis, represents the admission of failure — finally — by a leadership regime that had been in place for a decade.

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":380483,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,mobile,","session":"A"}']More significantly, it represents the official triumph of software over hardware.

RIM has been killed by the guys in the valley, who offer superior software platforms, Apple and Google. But it’s entirely another question whether RIM actually gets it. Listening to the new CEO Thorsten Heins, there’s no evidence he has what it takes to put RIM on track (as others are pointing out).

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

“It’s going to be continuity, Heins said lamely, in an interview with the Wall Street Journal about the shuffle. This rambling video of Heins doesn’t help much (see below). Although he has at least pushed to license RIM’s QNX operating system to other device manufacturers, something that others at RIM have resisted.

Only a few years ago, it was hard to predict the RIM downfall. But if you listened to Silicon Valley insiders, RIM’s decline has been inevitable for more than a decade.

RIM became known for its dead simple, really useful wireless email service. In 1998, RIM launched its first pager, the size of a bar of soap, and no one else was doing this near as nicely. C’mon! Email, streamed quickly and reliably over a fun little pocket-sized device? What’s not to like? RIM finessed its device, gaving birth to the “Blackberry” in 1999. The device won ardent fans among the plugged-in set, including Wall Street and other white-collar professionals. The power emailers. The device was too expensive for normal people, but BlackBerry won the hearts and minds of corporate executives. Over the next decade, it sewed up the enterprise market. It became known as the “CrackBerry.” People couldn’t put it down.

Meanwhile, BlackBerry continued to dominate. And in this way, Nokia, the largest cellphone maker, did too on the low-end with its “dumb phones.” Until circa 2007, it was the Golden Age of Hardware. The two companies perfected the hardware’s sync with phone networks. Voice quality was good and reliable. All RIM had to do was continue to make more of these useful phones, lower the price, and take ownership of the mass market. As BlackBerry became more entrenched, RIM’s leadership apparently became ever more certain of the company’s direction and superiority.

But in 2007 and 2008, the groundwork was finally laid for software’s resurgence.

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":380483,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,mobile,","session":"A"}']

Faster cell and data networks, at least in the U.S. and in many European and Asian countries, became ubiquitous. They became smarter too, offering things like location. Phones could also tap servers providing data over these upgraded networks to serve users with a plethora of useful applications. Then Apple launched its SDK, and the mobile app revolution was born. Third party developers used the network, and the phone, to offer their own services. Google’s Android launched shortly thereafter. RIM was left like a frog in a pot of slowly boiling water, clinging to what it thought was a safe world of superior hardware.

The context, of course, was ugly. RIMs company’s stock price lost more than three-quarters of its value last year. It never could get its software platform together: Through 2011, it suffered a significant worldwide BlackBerry outage. Due to inferior innards, its BlackBerry PlayBook tablet paled compared to Apple’s iPad, Amazon’s Kindle Fire and various other Android tablets. RIM then delayed a well-needed software update on the PlayBook until February. And its revamped, underlying operating system, the Blackberry 10 OS, was delayed until later this year, and was already being called a failure.

As it was, between June 2008, which is when the first GPS-enabled iPhone emerged, and June 2011, RIM’s shareholders lost almost $70 billion — or 82 percent of the company’s value. And its value has continued to decline. RIM is now worth a mere $8 billion, compared to Apple’s $400 billion. Apple, of course, is also a hardware company. But its focus on software, specifically the App Store, and the ecosystem of developers to supply apps to its platform, is what really helped Apple steal the show. And of course, Google, which never ever entered the hardware market, is the originator of the most popular smartphone platform, Android. And it did so by focusing on software, not hardware.

[aditude-amp id="medium2" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":380483,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,mobile,","session":"A"}']

It’s really about time that RIM’s leaders stepped down. Urgent change is needed. And the new guy, Thorsten Heins, whatever he does, needs to focus on software. Although it may be too late.

VentureBeat is holding its second annual Mobile Summit this April 2-3 in Sausalito, Calif. The invitation-only event will debate the five key business and technology challenges facing the mobile industry today, and participants — 180 mobile executives, investors, and policymakers — will develop concrete, actionable solutions that will shape the future of the mobile industry. You can find out more at our Mobile Summit site.

Chart credits: Yahoo Finance

[aditude-amp id="medium3" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":380483,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,mobile,","session":"A"}']

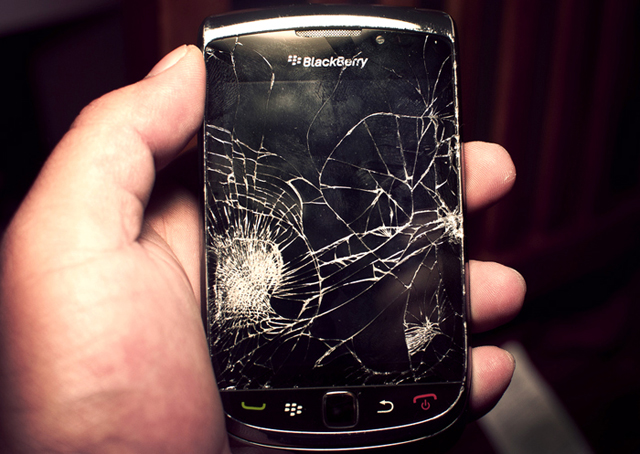

Broken BlackBerry image: Miggslives/Flickr

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More