On the same day the New York Times runs a story about how a faceless squad of hackers on the other side of the world has gone unchecked in a race to penetrate frightening chunks of the digital grid, I am sitting across from author, blogger, and activist Cory Doctorow.

He’s seated cross-legged, perched on a wooden table. The setting is an independent bookstore, where Doctorow proceeds to tell stories he’s told dozens of times already on this book tour — yet still manages to make them seem as fresh as they probably did the first time.

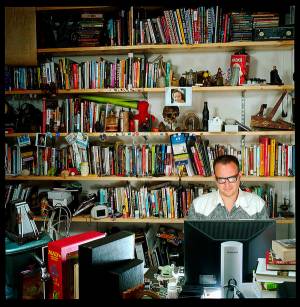

He sways, gestures invitingly, and adjusts his large-rimmed glasses, always in motion. He’s self-effacing, the way he calls himself a Patchouli-scented info hippie. And he talks with intensity of purpose, like a man always running out of time.

At his book signings, the co-editor of the website BoingBoing is not an author so much as a Jeremiah of the web. Never mind promoting “Homeland,” the follow to his 2008 bestseller “Little Brother.” He’ll get around to that.

Getting our policy badly wrong

First, he walks through a litany of episodes from the department of “truth is stranger than fiction.” He recaps examples of technology devices that have been co-opted and turned against their owners.

It’s partly our fault. One of the things wrong with the world, Doctorow insists, is that enough people aren’t demanding that devices be made differently, “so that people can see inside them.”

The default posture of computers is ‘Yes, master’ or ‘I can’t let you do that, Dave.’ It’s up to us decide, because the world we live in is made of computers. Your house is a computer. We are increasingly putting little computers inside our body. Your car is a computer that hurtles down the highway.

People are free when they know the reality of the world. Yet we continue to treat the Internet as though it were nothing but a glorified system for cable and phone calls.

Before he gets around to exposing the still-raw nerve that is his reaction to the suicide of his close friend Aaron Swartz, Doctorow continues with a segué that doesn’t let the public off the hook. He laments the frequency with which users tap “Agree” when confronted with Byzantine Terms of Service agreements and software updates, an action that’s a kind of mindless surrender to the complexities of the Internet age.

From there (and he still hasn’t yet bothered to beat his chest and tout the book that’s brought him here) he blasts prosecutors run amok and talks about how lawmakers “keep getting our policy badly wrong” when it comes to computers.

There’s no way to legislate what computer users can’t do or shouldn’t do, because no sooner than the ink has dried on that bill would such a law be rendered obsolete by the pace of technological change. Yet along the way, in Doctorow’s telling of the story, legal protection of the free flow of information gave way to a kind of mutual protection racket.

Information that’s supposed to be free and public got shut away, where it’s kept under lock and key.

Remembering Aaron Swartz

“I knew Aaron for more than half his life,” Doctorow said, bringing the discussion around to the loss of a pioneer of Internet freedom. “Aaron was one of those bright kids who blew the grading curve. His parents let him leave school.”

Years ago, Doctorow was dating someone who had volunteered to be Swartz’s chaperone around San Francisco when the young teenager was visiting and involved in Internet work far beyond his years.

“We picked him up,” Doctorow remembers. “I remember he was the world’s worst eater. We fed him awful food. I remember thinking, this kid’s going to go somewhere – if he doesn’t die of scurvy.”

Swartz, of course, went on to work at Reddit. He got wealthy but stayed restless and reckless. He couldn’t shut off his ambitiousness, Doctorow remembers, not when he was “liberating” 20 percent of the most widely cited case law from the PACER electronic court records system and not when he was taking advantage of MIT’s public wifi and downloading academic journal articles.

The researchers behind those articles, Doctorow said, are “uncovering tiny chunks of the truth of the world, and we don’t get to see it. If you’re a random person, you can’t get it. And that matters, because we don’t know where the next innovation will come from. I think the world is better when we know the truth of it.”

MIT kept locking Swartz down, Doctorow said, trying to tweak the network and kick him out. At one point, Swartz walked into a closet and plugged directly into the system and downloaded millions of documents.

A prosecutor brought charges against him, threatened decades’ worth of jail time. Swartz said he’d fight it. Doctorow recalled lawyers who “started to play dirty,” denying Swartz documents he was entitled to.

“He kept working,” Doctorow said. “You may remember that dumb law, SOPA. Aaron was one of the people who helped fight and kill that.”

Just over a month ago, Swartz hanged himself in his New York apartment. Doctorow says he’s still trying to make sense of that.

Drawing from life

It’s hard not to be reminded of Swartz in Doctorow’s new story, about a young hacktivist who’s detained and roughed up by the feds. As a matter of fact, Swartz helped Doctorow write the book.

“When I was working on this book, I asked Aaron for help,” Doctorow said.

Swartz sent Doctorow a missing piece he needed for the story. Doctorow didn’t know how he’d describe it, but he wanted to include a mention of a next-gen device that could be used to mobilize voters without needing to rely on the moneyed interests or power brokers who run the current political structure.

Swartz sent him a few paragraphs that Doctorow liked so much he used them verbatim.

Doctorow wraps up his brief remarks by turning to something he’s written down. He’s promised Swartz’s family he would talk about this on the book tour.

“These are things I would have said to Aaron if he’d called me.”

Doctorow’s voice wavers a bit. He presumes there are people in the crowd who’ve dealt with depression.

“I know I have.”

Trying to maintain a steadiness in his voice, Doctorow tells the crowd that “dead people can’t solve problems.” That whatever problems Schwartz was facing, killing himself didn’t solve them. “They will go unsolved forever.”

That “if he was lonely, he will never again be embraced by his friends. If he was despairing of the fight, he will never again rally his comrades with his brilliant leadership.”

And that’s it. There are questions from the audience, and Doctorow promises to “render your books un-returnable” by signing them.

One of the several things striking about him is the way he can pull off a difficult feat. He’s served to rally the faithful — this small crowd of the faithful, admittedly — in defense of the cause of Internet freedom. And he gives them marching orders, without even having to tell them what those orders are.

Photo credit: JonathanWorth.com