Publishers of novels, business how-to’s and technical manuals have managed to avoid having their products ripped and burned by online pirates. Unlike music and movies, scanning a book into digital format isn’t something anyone with a laptop can do.

Publishers of novels, business how-to’s and technical manuals have managed to avoid having their products ripped and burned by online pirates. Unlike music and movies, scanning a book into digital format isn’t something anyone with a laptop can do.

That’s about to change. As e-books and e-readers become more popular, it’s inevitable the book industry will have to deal with cracked copies of its wares being passed around the Internet.

People who share copyrighted books will be able to invoke the same justification used for sharing ripped music and movies: Most book authors only receive a fraction of the money readers pay to read their works.

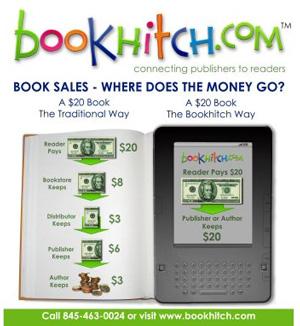

As the chart at right by online seller BookHitch.com shows, an author can receive as little as three cents of every dollar. That’s why people who break the copyright protection technology on an e-book and post it to BitTorrent won’t feel they’re robbing a writer. No, they’re sticking it to The Man.

In digitized form, a full-sized book is a smaller download than a popular song in MP3 format. As more and more titles are published electronically, there’s more and more incentive to figure out how to break the digital rights management software used by Amazon, Apple and others. Once you’ve cracked one book, you can crack thousands.

Book makers are the last holdouts against the mass digitalization of content over the Internet. But they know what’s coming. That’s why they’re trying multiple strategies to keep their businesses profitable. Big-name publishers Macmillan, HarperCollins and Hachette are moving from a wholesale-retail delivery chain to what they call an agency model. In the new scheme, Amazon is a selling agent told by each publisher exactly how much to charge for each book. In exchange, the publishers claim to be giving their agents a higher profit margin than they’d collect as a retailer.

Amazon, in return, launched a 70 percent royalty option a month ago. Authors or publishers who sell to Amazon’s Kindle users can keep 70 cents of every dollar spent on their books. In exchange for higher royalties, they must agree to list their books at much lower prices than the agency model publishers do. Macmillan wants $14.99 for most books. Amazon’s 70-percenters agree to sell for $9.99 max.

Startup companies like BookHitch.com want to kill the entire chain of price markups. Privately funded BookHitch, which operates from Poughkeepsie, New York, is built on the premise that there’s more money in marketing books than in selling them. Authors who sell through BookHitch get to keep the entire selling price of each book sold. BookHitch, which sells paperbacks, hardcovers, e-books and audio, makes its money instead by selling premium placement in the company’s online catalogue. That ad revenue more than covers the cost of selling the un-marketed titles, the company says.

The book industry is just like music and movies: A few hits pay for everything else. If readers stop paying for those hits, it’ll be a problem as bad for midtown Manhattan’s book makers as Napster and BitTorrent were for Hollywood. Steve Jobs’ iPad demo in January served as a final warning: Most people won’t buy a dedicated e-reader for books. They’ll use their personal computer if the books are available there.

Now that I can download a book in three seconds over my Comcast cable modem, the challenge for publishers will be to make it so easy and cheap to buy their books that I won’t bother Googling for a free copy.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More