Gaurav Jain is a Principal at Founder Collective, an early stage VC firm based in Cambridge and NYC that has made investments in 150 companies including Uber, Buzzfeed, and Makerbot. He cofounded Polar and was an early Product Manager for Android. Follow him @gjain.

As a VC, the number one question I get, repeatedly, is if we’re in a bubble. The answer is simple. No.

At least not like the one that peaked back on March 10, 2000 when the NASDAQ hit 5,132.52 in intraday trading, before cratering a couple years later at 1114.11. (As of this writing, it sits at 4,744.84).

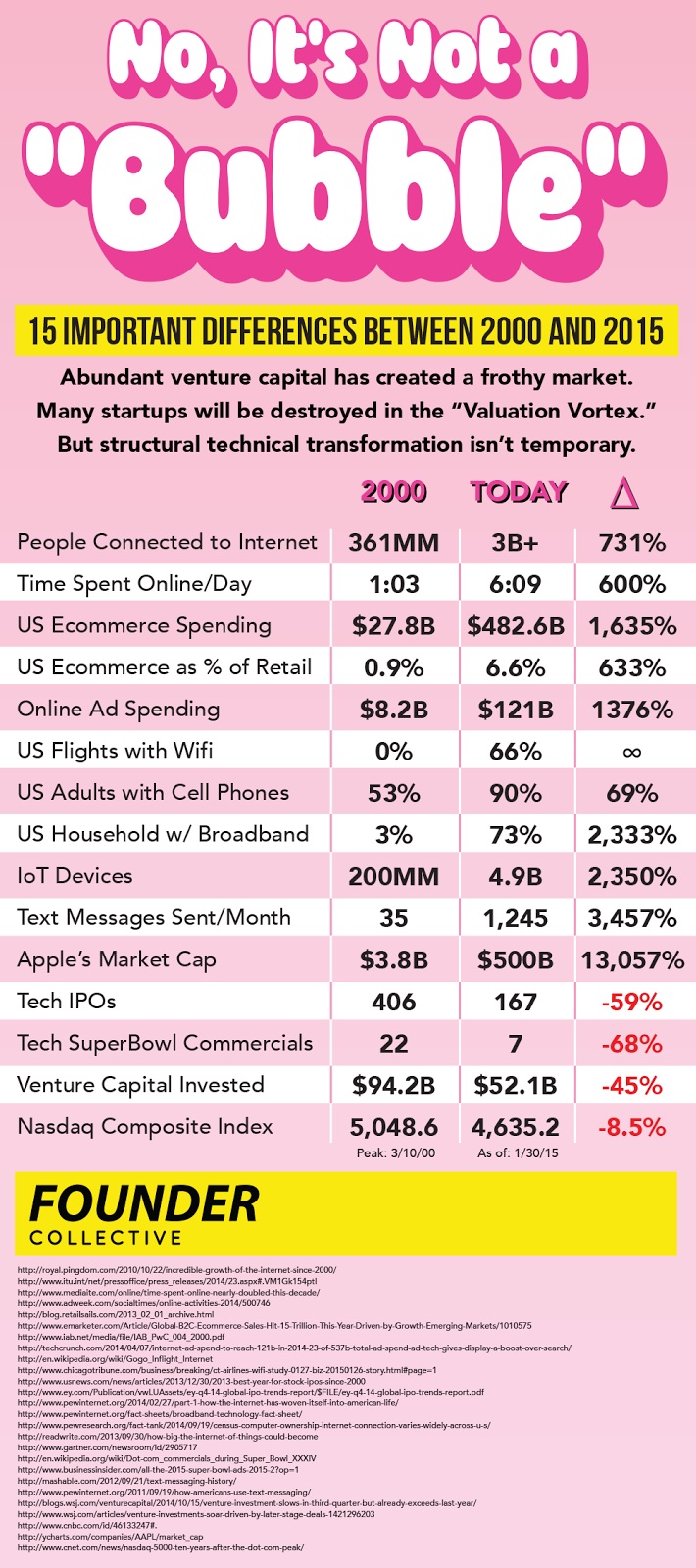

You might ask why I possess this irrational exuberance, or at least unwillingness to be pessimistic. Over the last 15 years, we’ve seen 10X growth in the number of people using the Internet, a 17X growth in the rate of online consumer spending in the U.S., not to mention nearly 40 percent inflation of the dollar. Despite those, and many other positive signs, we are still 4 percent below the dot-com bubble peak in the value of the NASDAQ composite.

The NASDAQ might drop precipitously, and there are plenty of reasons to believe that the exorbitant valuations startups are receiving will shrink. But this persistent fear of bubbles has more to do with our human tendency to stick with familiar narratives, especially as it relates to technology, rather than an evaluation of market fundamentals.

Beware familiar but faulty logic

Remember when Android was going to destroy iOS? The theory was that eventually, the sheer number of installed smartphones would make the economics of Android irresistible for developers. Apple would be consigned to the role of “also-ran” just like it was when it competed with Microsoft in the PC industry.

Instead, Samsung, the leading Android handset manufacturer, is hemorrhaging share, and app developers make 70 percent more revenue from the App Store than the Android equivalent.

Remember when pundits argued that Apple had to reduce the cost of its phones? Again, the PC industry “proved” that eventually prices will collapse, leaving Apple out-of-step with consumer demands.

On January 26, 2015, Apple announced the greatest quarterly financial results in history and an average selling price that increased dramatically.

So it goes with startup valuations. It seems that every time a company with a young founder, bold idea, and billion dollar valuation comes onto the scene, pundits invoke the 2000 tech bubble (usually with a snide joke about Pets.com).

Some will point to the fact that the amount of money VCs raised in 2014 ($32.9 billion) is up 60 percent from the prior year, but it’s actually lower than the record $85 billion raised in 2000, or even the more modest funds raised from 2005-2007, especially when factoring in inflation.

There’s no doubt that the funding environment is frothy, valuations for many companies are rich, and that some of today’s biggest name startups will face challenges (e.g. Fab), but the world has changed dramatically in the last decade and a half:

Here are 15 key differences between 2000 and 2015:

When was the last time you ate dinner without a Pavlovian impulse to check your phone?

When was the last time you ate dinner without a Pavlovian impulse to check your phone?

In the year 2000, the Internet was largely a novelty. Today it’s central to our existence. Toddlers navigate YouTube, commuters bury their faces in phones while on the subway.

44 percent of smartphone users sleep with their phones, and two thirds of smartphone owners take their surfing to the bathroom. The valuations of tech companies might drop, but they won’t evaporate as they did when AOL chatrooms were the web’s primary draw.

In 2000, web business models were immature, but in 2015 they power retail. In 2015, the e-commerce industry will grow to over $350 billion from $28 billion 15 years ago. In 2014, 40 percent of holiday dollars were spent online. $2.7 trillion will be exchanged globally online in 2015. E-commerce is a force to be reckoned with, and the industry has grown to a size that can easily accommodate many billion dollar companies. Advertisers have taken note of this shift and spent $121 billion to target these customers, accounting for 23 percent of the global ad spend. Critics will point out that Amazon, the e-commerce leader, isn’t consistently profitable, but as Benedict Evans notes, a company can only be unprofitable for 20 years by choice.

This trend is only getting started. Despite its massive growth, e-commerce only accounts for 6.6 percent of U.S. retail spending. Even the giant Amazon only accounts for 1 percent of total retail sales. Today, 10 percent of cars are currently connected to the Internet, but that number is predicted to rise to 90 percent by 2020. And think, health care, education, and government are three massive markets that have not yet embraced technology to the level that media and retail have.

The case for a soft landing

Let’s imagine that the worst case scenario hits and the stock market plummets by 20 percent or more. Here are some reasons things won’t be as bad as in 2000.

Cost to experiment and fail has dropped by several orders of magnitude: We know a lot more quickly now whether a business will work. In 2014, Kickstarter allowed tech and game entrepreneurs to raise $310 million dollars in non-dilutive funding directly from customers. The app Yo, a single person effort, signed up over a million users across the globe in weeks. And unlike 2000, these massive rounds of financing are typically directed towards companies who are showing meaningful progress, rather than the land grab style of investing that marked the first bubble.

Understanding tech companies is more of a science: One of the big reason the original bubble popped so dramatically, causing the NASDAQ to lose approximately 70 percent of its value, was because our methods of evaluating tech stocks were so crude. “Eyeballs” became a crude proxy for revenue.

In the last 15 years, our understanding of a company’s LTV, CAC, and other key performance metrics has improved significantly. As a result, today’s pillar tech companies look much more like old-line blue chippers than the Y2K-era flameouts. Google has a P/E ratio of ~27, Apple is at ~17. There is growth baked into these numbers, but it’s not irrational exuberance.

Increased late stage funding = longer time to IPO = less opportunity for retail investors to get burned: In 2000, 406 companies went public. In 2014, only 167 tech companies debuted in the public markets. The Sarbanes-Oxley regulations have helped shield retail investors from the wild swings that come with tech investing. (It’s also prevented them from participating in the upside, but that’s a story for a different post.) If a correction comes, it will hit VCs hard, but middle American brokerages will be spared the worst of the losses, essentially a reverse of the 2000 bubble.

This is still bad; it will cause many VCs to seize, and will create ripples across the tech economy, but we won’t see stories of grandmothers forced into poverty because they bet their nest egg on a specious tech stock.

Big tech companies have amassed a lot of cash: Apple has $178 billion of cash on its balance sheet — more than the market cap of 483 of the 500 S&P 500 companies. Microsoft has $90 billion of cash on hand. Google has $60 billion.

A lot of this money is used in infrastructure investments, like Google Fiber and data centers, which in turn increases the market for tech products. M&A activity, like Nest, Siri, and Yammer create new product categories that in turn create new opportunities for startups.

Let’s say something forces the market to plummet, the IPO window shuts, and VCs put away their checkbooks. Big tech companies will essentially be able to buy up a wide variety of assets, or the teams behind them, on the cheap.

Unlike 2000, successful tech companies will be able to salvage some value from the assets that these less successful companies built and prevent a disaster like we saw in 2001. If public and private financial markets fail to fairly value startups, cash rich tech companies will create a floor for their value.

For more insights from tech industry insiders,

explore VentureBeat’s selection of recent guest posts.

Winter IS coming

The market has been on a run since 2010 and according to the theory of random walks the probability is that we’ll face some leaner years ahead. Even if it’s not a “bubble” the tech industry is even more sensitive to changes in the macro environment than the broader market.

The global financial crisis in 2008 had nothing to do with tech, but it impacted startups in painful ways (remember RIP Good Times?). When lean years hit, it’s going to be challenging for everyone involved in tech. Entrepreneurs who have graced magazine covers will have to lay off hundreds of talented workers. Hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital will be lost. Progress will slow. But it will be temporary.

There has never been a better time to be starting and building a tech company. There is so much growth still ahead of us. More than four billion people are waiting to be connected to the Internet and even mature areas, like e-commerce, are still only in the single digits of penetration. There will be bumps, but don’t expect another bubble pop.