Can 23andMe promote itself and keep your data secure?

Above: An ad for 23andme popped up last month on my Facebook page

23andMe describes itself as a genetics testing company, but arguably, it’s more of a citizen science effort. The company often repeats its goal to harness the “power of one million people” and provide a crowdsourced database for the purposes of breakthrough science and research.

For this somewhat utilitarian goal, 23andMe has become the master of marketing and self-promotion. To that end, the company recently recruited a new president, Andy Page, the former president of luxury online shopping site Gilt Groupe.

In the past five years or so, 23andMe has built integrations with Facebook and started advertising its service on various social media sites as well as broadcast TV networks.

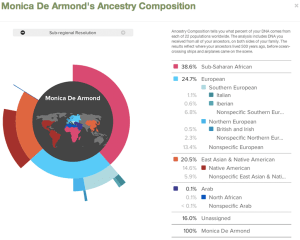

In addition, the company actively encourages its customers to share test results on Facebook, which is a highly effective customer acquisition tool. The company has popular features like a tool to create a melody out of your DNA and an “ancestral composition” service. 23andMe claims it can tell you the percentage of your DNA from 22 worldwide populations. Many customers feel compelled to share that they’re part Jewish or mostly hail from Sub-Saharan Africa.

23andMe has not developed an easy way to share health risks, although it’s certainly possible, and many people do, as evidenced by many of the comments on a recent Marketwatch article titled “Would you share your DNA on Facebook?”

On top of all this, 23andMe has an open API to allow third-party developers to mine genetic data. Customers determine whether to grant developers access to the app that uses the API.

This is a strikingly open and social approach, which is somewhat surprising given that 23andMe is dealing with some of the most sensitive information any company can possess.

Privacy experts fear that 23andMe is not doing nearly enough to keep your data secure. One Silicon Valley geneticist I interviewed, who requested anonymity, quipped that sharing 23andMe results online is worse than sharing bank account information: Your financials will likely change, but your genes never will.

Above: A 23andMe customer shares her ancestral composition

Policy analyst and attorney Sarah A. Downey argued a similar case in a recent VentureBeat article. 23andMe’s data collection is akin to having a company “know your entire genetic code.” (Note that 23andMe is still in the exploratory phase when it comes to gene sequencing, and does not currently sequence your entire genome. More on that later.)

Downey has a point: 23andMe’s terms of service are hardly airtight. The company can give up your DNA if it receives a court order, and your data may be used for the purposes of research and development. Moreover, it is not clear what will happen to your genetic information in the event of an acquisition — as when rival Navigenics was scooped up by Life Technologies Corp.

“Even if they only let 50 people look at your DNA, you still don’t know who they are,” said George Church, genetics professor at the Harvard Medical School and a founder of the Personal Genome Project, in a recent interview.

Should you be paranoid?

23andMe’s Afarian admits that we’re still very early in our understanding of genetics, and the laws that protect consumers are still evolving.

In an in-depth interview, I asked her whether relatives are at risk when you share your genetic information. Afarian said it “depends on your family member,” as you might not inherit the same health risks as all your siblings.

Above: Customers sharing 23andMe results via Facebook

It’s a reasonable response but doesn’t really work in practice. Imagine a scenario where it’s a close race between several qualified job candidates. An employer might conduct an Internet search on one of the recruits, discover that they have a high risk of getting Parkinson’s disease (or a close family member is), and make the decision to hire someone else. That recruiter or employer could cite any number of reasons for that decision.

That would be illegal. But that doesn’t mean it won’t happen.

In 2008, the Bush administration passed the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), which protects employees with pre-existing health conditions from being discriminated against at work. In theory, if you have a high risk of contracting breast cancer or Parkinson’s disease and you share this information publicly, you shouldn’t be affected — in a perfect world.

“There is a vast difference between implementation and enforcement,” said Lauren Fifield, a senior health policy strategist at health IT startup Practice Fusion, and genetic discrimination is very difficult to prove.

Furthermore, 23andMe customers who choose to share ancestral composition risk race-related discrimination. Fifield cites another potential concern: “Romantic interests who opt against marriage and children” based on a potential mate’s genetic profile (although arguably, you might not want to marry someone who makes decisions that way anyway).

To make matters more complex, the U.S. is one of the few countries where laws exist at all to prevent genetic discrimination.

23andMe has long been aware of this potential issue but has not taken steps to educate and inform consumers. Instead, it downplays the potential effects.

Alex Khomenko, one of the first engineers at 23andMe, developed many of the Facebook integrations. He’s aware that customers may be discriminated against for sharing information from test results. “Like any form of discrimination, it will happen occasionally,” he said.

But he hasn’t heard about any negative consequences, such as genetic discrimination at work or insurance companies denying health insurance, based on their risk of disease.

“I am less concerned about this scenario in practice,” he said.