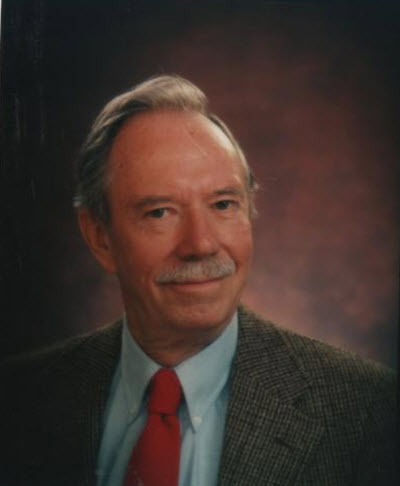

Charlie Walton, the inventor of an ubiquitous wireless technology known as RFID, has passed away at 89.

Charlie Walton, the inventor of an ubiquitous wireless technology known as RFID, has passed away at 89.

Walton, who lived in Los Gatos, died on Nov. 6, according to his wife Ann Walton. I once wrote an article about Walton while at the San Jose Mercury News and his efforts to proselytize RFID, known in long form as radio frequency identification.

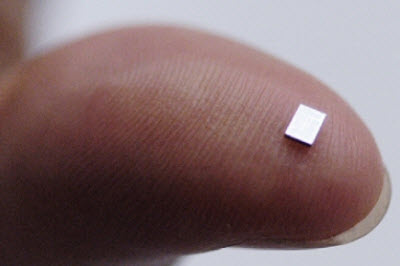

These are the chips that go into the access control devices, so you can slap a badge across a reader to open the door to an office. They are also used in car locks and on shipping pallets so that companies can track expensive goods. Every time you use one of these chips, it would be nice if, once in a while, you thought about the man who invented them.

The passing of Steve Jobs recently gave Silicon Valley its first real experience with the mortality of the technology legends that we have all grown up with. But Walton’s passing reminds us that there are inventors who have toiled away in relative obscurity. Walton pioneered the technology as a lone inventor in the 1970s and 1980s, but it came into its own in the last decade as the cost of making the tiny chips came down to a matter of pennies. Walton made a few million dollars from the invention, enough to keep him inventing technology for the rest of his days.

“I feel good about it and gratified I could make a contribution,” Walton told me in 2004.

RFID is expected to generate $6 billion in worldwide revenue in 2011, according to ABI Research. The chips are used in access control, car immobilization, electronic toll collection, electronic document identification, dog tags, asset management, baggage handling, cargo tracking, contactless payments and ticketing, and supply chain management.

RFID is expected to generate $6 billion in worldwide revenue in 2011, according to ABI Research. The chips are used in access control, car immobilization, electronic toll collection, electronic document identification, dog tags, asset management, baggage handling, cargo tracking, contactless payments and ticketing, and supply chain management.

The chips transmit information about a product’s location and use over short-range radio waves to a computer, where the data can be cross-checked with a database. Libraries use RFID readers to track books, and hospitals use them to track drug bottles. In 2007, Walton wrote a book about the things around us that we cannot see entitled, “The Space Before Your Face.”

Back in the 1970s, bar codes were the main competition. At 25 cents each, they were hard to beat. Walton’s first RFID cards cost $1.75, and so bar codes beat out RFID for use in scanning grocery items at supermarket checkout scanners.

RFID had been around in different forms before Walton created a radio-operated door lock, but his design became popular. With his tags, a tiny electrical current from a radio transceiver, or RFID reader, wakes up a dormant card and gives it enough power via the wireless connection itself. That power gives the card enough power to generate a response. Walton’s first patent to mention RFID was filed in 1983, but the first patent that he got on the technology (No. 3752960) was granted in August 1973. That patent was later reference by dozens of later inventions.

The invention earned Walton some recognition. He appeared on the TV quiz show “What’s My Line? And his invention was mentioned in articles about electronic locks in Business Week and Popular Science in 1973.

The invention earned Walton some recognition. He appeared on the TV quiz show “What’s My Line? And his invention was mentioned in articles about electronic locks in Business Week and Popular Science in 1973.

Like many inventors of his era, Walton grew up as a ham radio enthusiast. He was raised in Maryland and New York and studied electrical engineering at Cornell University. He went to work at IBM’s research labs in 1960. there, he studied analog and digital computing. In 1970, he struck out on his own as an inventor with his own company, Proximity Devices, in Sunnyvale, Calif.

He showed his RFID technology to the board of General Motors, but they rejected it as “too Buck Rogers.” In his career, he collected more than 50 patents. He went for a year without a salary. Finally, he got lucky licensing it to lock maker Schlage, which used it to make electronic locks that can open by waving a key card near a reader (pictured in a San Jose Mercury News photo at top).

The first RFID card key was passive. It used no battery power itself and was awakened when it came within six inches of a reader. It was bulky at first, but then it was integrated into chips and miniaturized over time. In 1980, he also got a patent for a digital version of RFID, which could change data on the cards. The low-cost led to its widespread adoption in the past decade.

After about a decade, Walton said he began to make good money from the patent royalties. I visited his home on a two-acre lot in the hills of Los Gatos. I recall he had a toy train set on a big pool-table-size board with all of the accompanying scenery. Walton rigged it to a pulley that would raise the board and keep it out of sight when it wasn’t in use. It was clearly the creation of a natural tinkerer. As we walked the grounds, Walton pointed out that he invented a better gopher trap as well.

After about a decade, Walton said he began to make good money from the patent royalties. I visited his home on a two-acre lot in the hills of Los Gatos. I recall he had a toy train set on a big pool-table-size board with all of the accompanying scenery. Walton rigged it to a pulley that would raise the board and keep it out of sight when it wasn’t in use. It was clearly the creation of a natural tinkerer. As we walked the grounds, Walton pointed out that he invented a better gopher trap as well.

In some ways, Walton’s RFID patents were bittersweet. His last royalty-bearing patent expired in the mid-1990s. That meant that he wasn’t able to cash in on a giant windfall as big entities such as Wal-Mart and the Department of Defense began in the past decade to require supplies to put RFID tags on millions of warehouse goods. Patents, by law, run out after 17 years. The old bar code rivals are still around, but RFID is here to stay.

There will be a memorial service for Walton on Dec. 18 at 3 pm at the Los Gatos Unitarian Fellowship.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More