A variety of social network gaming applications are making lots of money from virtual goods. But could these services soon find themselves in trouble for allowing gambling — and get slapped with large fines or other punishment? The question matters like never before, and the answer’s not clear — although from my research, the risk seems relatively low.

A variety of social network gaming applications are making lots of money from virtual goods. But could these services soon find themselves in trouble for allowing gambling — and get slapped with large fines or other punishment? The question matters like never before, and the answer’s not clear — although from my research, the risk seems relatively low.

Some companies, like Zynga, are rumored to be bringing in revenues of more than $100 million through games like Texas Hold ‘Em poker. This year alone, companies on Facebook’s platform could see $500 million in total revenue, and most of it is in the form of virtual goods purchases and advertising-based offers. Add in MySpace, other social networking sites with developer platforms — and soon, the iPhone — and you can see how big this market already is, and will be.

The government has yet to make clear rules defining some forms of gambling in social games, especially when it comes to regulating virtual currencies and games. Until then, entrepreneurs need to be pro-active about not crossing the line, as a former federal prosecutor, a gambling-industry attorney and other legal experts tell me. The market is just that young.

What does the law say?

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

Generally, the Congressional Wire Act of 1961 bans any organization from transferring gambling-related funds between states or in and out of the country. The federal government has used the Wire Act to prosecute internet gambling-related sites in recent years, as well as affiliated organizations, such as local radio stations that have run gambling ads. The Act’s relevant language:

Whoever being engaged in the business of betting or wagering knowingly uses a wire communication facility for the transmission in interstate or foreign commerce of bets or wagers or information assisting in the placing of bets or wagers on any sporting event or contest, or for the transmission of a wire communication which entitles the recipient to receive money or credit as a result of bets or wagers, or for information assisting in the placing of bets or wagers, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

But what is gambling on an application? The consensus among lawyers and entrepreneurs I’ve spoken with is that the app can’t let a user put something of value in, play a game of chance, and get real money out. For some games, like poker, things are a little bit more vague. Some states consider it a game of chance and so lump it in with other forms of illegal gambling. Other states consider it a game of skill, and in some form they may allow it. California, for example, has given out a limited number of municipal poker licenses.

But what is gambling on an application? The consensus among lawyers and entrepreneurs I’ve spoken with is that the app can’t let a user put something of value in, play a game of chance, and get real money out. For some games, like poker, things are a little bit more vague. Some states consider it a game of chance and so lump it in with other forms of illegal gambling. Other states consider it a game of skill, and in some form they may allow it. California, for example, has given out a limited number of municipal poker licenses.

At the same time, some forms of contests are permitted nationally, like free sweepstakes offers.

One risk, in any case, is that an application company — and possibly a social network that hosts an application — could be found liable for any gambling that users conduct within the application. For more on that, see this article, “Assessing liability of social networking sites,” by lawyer Joseph V. DeMarco, published last fall in the law journal World Online Gambling Law Report (fee required).

Another risk is that sites suspected of allowing gambling will get cut off from U.S. credit card transactions. Internet gambling sites come in a variety of forms, from for-pay poker social networks to sports betting to much else. But instead of going after every single site that might be gambling, the government has gone after financial institutions that conduct transactions like credit card payments for gambling sites. In 2006, Congress passed the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act; it forbids financial institutions from working with gambling sites, except for specific things like online lotteries, fantasy sports, and horse racing. As a result, financial services companies have stopped working with many these sites, and cut off their revenue.

Aside: There’s a bill now trying to legalize online gambling, championed by Barney Frank, a Democratic representative from Massachusetts.

But we’re talking virtual goods and currencies here — these can be either legal or illegal, depending on how they are used. Legal issues around virtual goods and gambling have only been tested out in other web services that generally use virtual goods. Prior to the rise of social networking platforms in the last couple of years, virtual goods and currencies were mostly found in the Western world in hardcore massive multi-player games like World of Warcraft or quirky virtual worlds like Second Life. The virtual goods business model has been far more common in Asia, driving profits for big companies like Tencent for years. Social networking platforms have made it much easier for friends to play games against each other, and compete for status within a game — the sort of mechanic that drives virtual goods sales.

But we’re talking virtual goods and currencies here — these can be either legal or illegal, depending on how they are used. Legal issues around virtual goods and gambling have only been tested out in other web services that generally use virtual goods. Prior to the rise of social networking platforms in the last couple of years, virtual goods and currencies were mostly found in the Western world in hardcore massive multi-player games like World of Warcraft or quirky virtual worlds like Second Life. The virtual goods business model has been far more common in Asia, driving profits for big companies like Tencent for years. Social networking platforms have made it much easier for friends to play games against each other, and compete for status within a game — the sort of mechanic that drives virtual goods sales.

Years ago, third parties tried to use Second Life’s virtual currency to set up full-fledged online casinos. Facing a federal investigation into third-party casinos operated in Second Life, as well as possible loss of access to credit card companies, owner Linden Labs banned all forms of gambling. That outcome wasn’t too surprising: The Second Life virtual currency, Linden dollars, could clearly be bought with real money, gambled, and cashed out.

To take another example, in World of Warcraft, you can also earn virtual gold — large black market sites have sprung up trying to illicitly buy and sell this gold, and use it in gambling. Game owner Blizzard avoids legal trouble by aggressively trying to shut down these sites and their activities.

What’s happening on social networks applications is at least somewhat different. Let’s take closer a look.

Defining the value of virtual goods and currencies

Most games let you either buy a currency directly or earn it through advertising offers; rent some movies from Netflix, get some virtual poker chips. These offers clearly have a monetary value to the advertiser, the game developer and the user. Clearly, the first requirement of gambling — that money goes into the system — is being met.

What about game-play — where’s the chance, or skill, the second qualification for gambling? Each game made by each developer might have a slightly different twist on the game-play dynamics. It doesn’t really matter, though, as it’s perfectly legal to play any sort of game as long as you can’t get money out. Even in the real world, it’s not always clear where the authorities draw the line. In Japan, for example, casino-style game Pachinko lets you earn currency in the form of small metal balls, which can then be traded for real-world items — or cash, under the ignoring eye of the Japanese police.

What about game-play — where’s the chance, or skill, the second qualification for gambling? Each game made by each developer might have a slightly different twist on the game-play dynamics. It doesn’t really matter, though, as it’s perfectly legal to play any sort of game as long as you can’t get money out. Even in the real world, it’s not always clear where the authorities draw the line. In Japan, for example, casino-style game Pachinko lets you earn currency in the form of small metal balls, which can then be traded for real-world items — or cash, under the ignoring eye of the Japanese police.

A key question, according to all of the lawyers I’ve spoken to, is how you define the value of a virtual good. Matt Jacobs is a Sacramento-based former federal prosecutor who was introduced to me through a source skeptical of the legality of some gaming activities in social networking apps. Having worked on gambling-related cases, he tells me this:

One of the potential issues in some games is how you get virtual goods out. Game developers will say ‘they’re not really being played for money, that what you win is not money.’ I’m not sure that this ultimately works. You’re getting something of value, or at least of arguable value. These goods are advertised as costing money, even just a buck or two. You can win virtual currency that’s clearly equivalent to real money, and use that to buy virtual gifts.

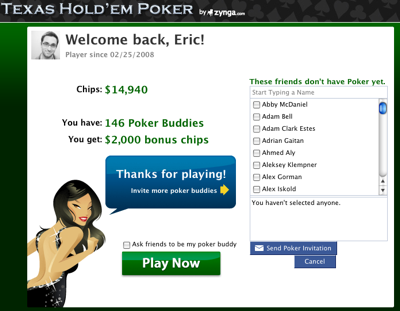

Let’s take the most prominent example of a game application, Zynga’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and see how it fits or doesn’t fit the definition of gambling. This game has comprised a large portion of the company’s revenue to date, and has helped it to more than 10 million daily active users — Zynga is currently the largest and most profitable app developer that I am aware of.

When you first start playing the game, you get chips worth $2,000 in the game’s virtual currency. To be clear, the dollar sign doesn’t mean real money — like many other games, Hold ‘Em uses the symbol to make the experience feel more life-like, Pincus tells me. Every time you login, you get thousands more free chips. And, like in real poker, players earn more chips through winning games. When you get more chips, you get special status indicators and access to high-chip tables where you can compete against the best players.

The game also lets you either buy virtual poker chips or take advertising offers to get them. If you want to get into the top tables or otherwise look like a pro even though you’re not, these mechanisms are how you do it. So money is going in. But what happens to it? Basically nothing, Zynga chief executive Mark Pincus explains. You can’t take money out of the game in any form of value; you don’t even win virtual prizes that might possibly be worth money.

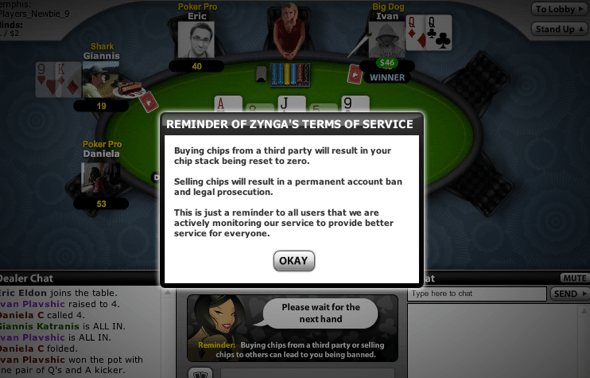

But there’s a second-hand market for Zynga chips (see this Google results page for a bunch of these chip-selling sites). Credit card fraud rings buy up chips on Texas Hold ‘Em then re-sell them to players, typically through agreeing to meet in private rooms and purposefully losing poker games to the purchaser, Pincus says. His company has built up an internal fraud engineering group to aggressively fight fraudsters.

Being proactive about stopping second-hand markets is what companies need to do in order to stay above the law, gambling-industry expert lawyer and Zynga representative Anthony Cabot tells me — like what World of Warcraft has already done. Zynga retained Cabot to check that it’s games are legally compliant. His opinion is that they are. Zynga has also conducted user education throughout its application and hired Cabot and other lawyers to enforce its terms of service and prevent fraud.

When does a gift become valuable?

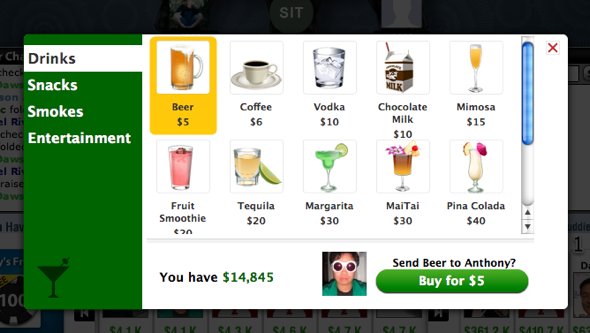

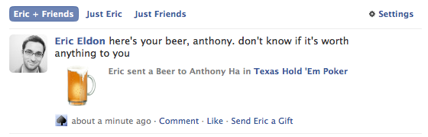

However, one seemingly gray area is that the Zynga app lets you send gifts to other poker players, like this virtual beer that I sent to colleague Anthony Ha. These gifts cost various amounts of chips (as displayed in dollar amounts). When you send somebody a gift, you see it on your Facebook wall and they see it in their homepage stream of activity. Some of these gifts, incidentally, also look a lot like Facebook’s own virtual gifts — which cost Facebook “credits.” Like Zynga’s poker chips, these credits can be bought using real money. But Facebook gifts work differently than Zynga’s poker gifts. Zynga’s poker gifts can’t be placed on other people’s walls, while doing that isn’t just an option for Facebook gifts but the reason they exist. So how does one define value here? Could the very act of placing a gift on your own wall — that you send someone else — be defined as getting money out? Could the visual similarity of Zynga gifts to Facebook gifts somehow imply that Zynga’s gift have similar value to Facebook gifts? The law is not clear on these matters.

For its part, Zynga doesn’t believe it is doing anything illegal here. These gifts are meant as a way of encouraging people to play poker more, Pincus explains — the point of the application, at its core, is to get people playing it as much as possible and competing for status. In terms of these gifts, Facebook limits Zynga’s users to sending only 16 gifts per day. The gifts cost between five and ten chip-dollars in the game. Users are being given a far greater number of chips per day. By this measure, the gifts are possibly worth as little as zero dollars in the game. Specifically, if you use Poker to send 16 gifts to your friends each day, displaying those gifts in their streams and on your home page, are you realizing any value outside of the app?

For its part, Zynga doesn’t believe it is doing anything illegal here. These gifts are meant as a way of encouraging people to play poker more, Pincus explains — the point of the application, at its core, is to get people playing it as much as possible and competing for status. In terms of these gifts, Facebook limits Zynga’s users to sending only 16 gifts per day. The gifts cost between five and ten chip-dollars in the game. Users are being given a far greater number of chips per day. By this measure, the gifts are possibly worth as little as zero dollars in the game. Specifically, if you use Poker to send 16 gifts to your friends each day, displaying those gifts in their streams and on your home page, are you realizing any value outside of the app?

It certainly seems a stretch to call these gifts an instance of cashing out, but the law isn’t clear about how to value or not value virtual goods when they leave an application. Zynga is most likely fine in this instance, but all sorts of games use gift-sharing on Facebook itself. In some instances, a developer might choose to make it very expensive to send a gift to a friend through a game — making that gift worth more to users. When that gift gets posted on Facebook streams and walls, it could be quite valuable to users.

Conclusion: Caution

Stepping back, it’s hard to know if or how the government may try to prosecute social gaming companies. As a sign of this ambiguity, some lawyers who provided background for this article declined to go on the record because they were uncertain of where things might end up — and what positions their clients may end up taking as a result.

The scenarios are all over the place. Perhaps a gung-ho state attorney general will decide that social games are somehow gambling and try to get some headlines by going after the entire industry. This has happened to other popular web services, seemingly not because they are doing anything particularly bad, but because they are publicly-recognizable targets. Craigslist has been hounded by some attorney generals because prostitution rings use the service to advertise to customers — but the same attorney generals haven’t gone after print publications and other properties that run similar forms of advertising. Social networks themselves, including Facebook and MySpace, have also been targeted by attorney generals, allegedly because the sites haven’t done enough to protect minors from pedophilia — that’s even though many studies have shown that these social networks don’t see nearly as much of this activity as other sites.

The scenarios are all over the place. Perhaps a gung-ho state attorney general will decide that social games are somehow gambling and try to get some headlines by going after the entire industry. This has happened to other popular web services, seemingly not because they are doing anything particularly bad, but because they are publicly-recognizable targets. Craigslist has been hounded by some attorney generals because prostitution rings use the service to advertise to customers — but the same attorney generals haven’t gone after print publications and other properties that run similar forms of advertising. Social networks themselves, including Facebook and MySpace, have also been targeted by attorney generals, allegedly because the sites haven’t done enough to protect minors from pedophilia — that’s even though many studies have shown that these social networks don’t see nearly as much of this activity as other sites.

It would be a shame if the emerging social gaming industry were singled out because grandstanding politicians think it will get them more headlines than going after more obviously gambling-themed sites. Companies like Zynga are pioneering new revenue models that don’t seem to go against the spirit of gambling laws, and in my non-expert opinion they should be left alone to innovate as long as they are not clearly breaking the law.

Or, perhaps Frank’s congressional bill that I mentioned earlier will get passed, and this will all become moot?

For now, entrepreneurs will be best served by giving extra thought to how they set up game mechanics. And, it might be time to retain a gambling attorney to go over any specific issues.

[Image credits: Second Life slot machine via Shon-Ting Fu; WoW image via Associated Content.]

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More