Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

The two hundred people packed into a small screening room in Midtown Manhattan on a recent Tuesday night made quite a throng. Engineers, venture capitalists, and entrepreneurs sipped Sam Adams and nibbled bits from a fruit plate. They were there to learn about CrowdControl, a New York startup that is melding human workers with artificial intelligence to create the next paradigm for global labor: crowd computing.

The two hundred people packed into a small screening room in Midtown Manhattan on a recent Tuesday night made quite a throng. Engineers, venture capitalists, and entrepreneurs sipped Sam Adams and nibbled bits from a fruit plate. They were there to learn about CrowdControl, a New York startup that is melding human workers with artificial intelligence to create the next paradigm for global labor: crowd computing.

The crowd filtered into the theater, and Kirill Shenykman, a venture capitalist who had recently led a $2 million investment in CrowdControl, took the stage. “What we are trying to do is to transform human labor into something that scales like software,” he explained. “We’re trying to take people and make them into bits.”

A few, dark chuckles went through the crowd. With his deep voice, slight Russian accent, and coiffed silver hair, Shenykman seemed like a bit of a James Bond villain describing a master plan for world domination. “I don’t mean that in a negative way, a diminutive way,” Shenykman said, waving his hand. “But just as Amazon can provide computing power on demand to a growing startup, we want to be able to offer an elastic marketplace for human labor.”

CrowdControl takes large complex jobs and breaks them into tiny pieces, then sources the piecework out to millions of micro-task workers around the world.

AI Scaling Hits Its Limits

Power caps, rising token costs, and inference delays are reshaping enterprise AI. Join our exclusive salon to discover how top teams are:

- Turning energy into a strategic advantage

- Architecting efficient inference for real throughput gains

- Unlocking competitive ROI with sustainable AI systems

Secure your spot to stay ahead: https://bit.ly/4mwGngO

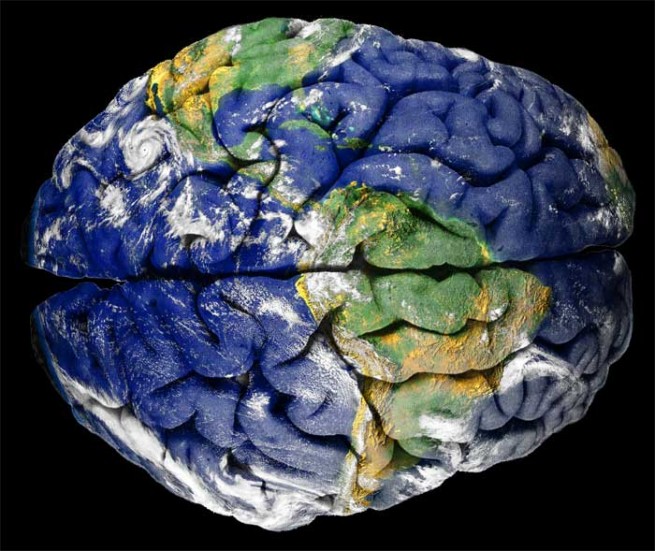

The company’s founder, Max Yankelevich, joined Shenykman onstage. “What we are doing is tapping into the world’s cognitive surplus,” he said, referencing a concept first laid out by digital intellectual Clay Shirky. “When you stop to think about the amount of brain power we have on demand, it’s kind of staggering. If we wanted to, with all the available excess on hand, we could recreate Wikipedia from scratch in a single day.”

– – –

The star of the show that night was Mechanical Turk, a service Amazon initially created in 1995 to deal with its own problems sorting its massive inventory.

“We came at it programmatically from every angle we could think of, but it wasn’t working,” said Heidi Bretz, a business development manager at Amazon. “We would have a pair of red shoes listed on the site, with a description for a red sofa, priced like a different pair of rouge shoes. It was a mess.”

Eventually the company conceded that there is some work that humans are simply better at doing than machines. So Amazon decided to offer the work up to its customer base. They would post a job to their site — sorting the color of shoes or types of chandeliers — and web users from around the world picked up the work, often for just a few pennies per chore. The result was such a success that Amazon decided to open up the marketplace to other companies. “When things work internally, we like to turn around and sell them as a tool,” said Bretz.

The name for this platform came from The Turk, a chess-playing automaton which cut a swathe through the ranks of 18th century gamers in Europe and America. It was only decades later that this brilliant thinking machine was later revealed as a hoax: a chess master hidden inside a box. Amazon’s system attempts a similar sleight of hand, organizing people from across the globe to work as efficiently as a giant machine.

The name for this platform came from The Turk, a chess-playing automaton which cut a swathe through the ranks of 18th century gamers in Europe and America. It was only decades later that this brilliant thinking machine was later revealed as a hoax: a chess master hidden inside a box. Amazon’s system attempts a similar sleight of hand, organizing people from across the globe to work as efficiently as a giant machine.

“The idea is you might sit down to a computer, log onto the web, order up a task, just as you would with any other piece of software,” says Prof. Rob Miller, who works on crowd computing at MIT. “You get the data back, all without ever realizing there was a human being on the other end of that transaction.”

Anyone can put a HIT — human intelligence task — onto Mechanical Turk, and anybody else can do the work. But the complexity in this kind of system was limited. “They should call them SHITs,” Shenykman, the investor. “Stupid Human Intelligence Tasks. With CrowdControl, we’re going to go much further.”