I’ve been silent about this #GamerGate scandal that has sent waves through the circles of game journalists, indie developers, gamers, and feminists. It was born from an ugly public fight between two lovers, game developer Zoe Quinn and her ex-boyfriend Eron Gjoni, after Gjoni posted a 9,000-word tell-all about Quinn and her alleged affairs with men, including a game journalist. It really was too much information about a lover’s quarrel.

But somehow, the story got legs. It exploded into charges of corruption in game journalism, and it brought on the online trolls, who attacked Quinn as well as other outspoken women for allegedly attacking the male-centric bias in games.

GamerGate supporters, who used the hashtag #GamerGate on Twitter, defended their culture and attacked the feminists and establishment game journalists. But the extreme tactics of making death threats and rape threats, coupled with sensational media posts and social media arguments, turned the topic into a conflagration. The #GamerGate crusaders felt like they were uncovering a great deal of corruption and feminist bias, much like the investigators who say that have found a liberal bias in the political media. And like the Anonymous hacking group, a small minority of people involved in the headless organism took matters into their own hands.

My approach was “tl;dr,” an Internet abbreviation that means “too long; didn’t read,” because there was just too much stuff to wade through. I was waiting for it to go away. But the death and rape threats found new victims, and that very much kept the story alive. My GamesBeat colleague Jason Wilson compared the whole scandal to McCarthyism, the crusade to root out communists in American society. I agree it is an apt comparison because the cynical Sen. Joseph McCarthy was so adept at keeping his witchhunt in the news.

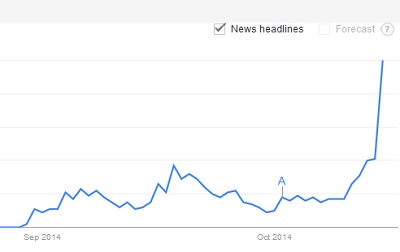

If you look at this Google Trends chart depicting mentions of #GamerGate, you can see that it started to go away, but it keeps popping back into the zeitgeist with each new incident, like this past week, when outspoken female game developer Brianna Wu had to move out of her home and feminist advocate Anita Sarkeesian had to abandon a university talk in Utah. Intel also accidentally stepped into the pile of s*** when it pulled its advertising from the game dev news site Gamasutra, because of a pro-feminist column by writer Leigh Alexander.

The New York Times has waded into it, and so has CNN. Stephen Totilo, the editor of game site Kotaku, has had to weigh in on a couple of editorials, one related to the ethics practices of his publication and another to the whole controversy itself. Some publications have used the opportunity to point to the corruption among gamers who have become celebrities on YouTube and have taken money from game companies to promote games — without disclosing that.

I don’t want to be the last game journalist in town to write about #GamerGate. I’ve had more time to think about what I want to say. I didn’t want to get dragged into the mudslinging and pulled away from what was really important in the game industry.

And it’s time to get off that fence.

First, I think it has become so complicated that it’s worth going back and reading a big pile of stuff to understand it. You’ll read things that simply disgust you, and even after you do that, you may still not understand what the heck is going on and who are the opposing forces in this war of words. If you oversimplify the controversy and take a stand in the wrong thing, as Intel did, you may wind up sending the wrong message. Intel, for instance, had to backpedal and say that it did supports the equality of women and the goodness of diversity.

“We recognize that our action inadvertently created a perception that we are somehow taking sides in an increasingly bitter debate in the gaming community,” Intel said. “That was not our intent, and that is not the case.”

Those who sit on the sidelines are being urged to make a choice, as silence suggests that you condone some of the extremist tactics. Advocates on both sides are trying to drag big game companies into the matter. That’s a consequence of the new trend toward “listening to gamers” at places such as Electronic Arts. People want the big corporations to recognize their particular stances as the most reasonable and mainstream points of view. To the advocates, I would urge some patience, as silence doesn’t mean you condone something. It may mean that you just haven’t thought about it because you’re too busy doing the thing that you really should be doing, which in this case is something like making great games. Some say it would be a tragedy if talented game designers flee the industry because of the Internet mobs, but it’s also a tragedy if an issue like #GamerGate takes the game designer out of circulation because they’re too busy arguing with someone.

Before anyone takes that stand and wades into the morass, they should find and read a timeline like this one. Or just take a look at this (fake) CNN graphic, below, that tries to simplify it all. The problem with that graphic is that those borders between the groups are increasingly imaginary lines. The result, as Kotaku’s Totilo noted, is chaos.

The worst way to try to understand #GamerGate now is to type it into a Twitter search, because the most bizarre things come up.

“Threats of violence and harassment are wrong,” the Entertainment Software Association, the main lobbying group for big game companies, said in a statement to the New York Times. “They have to stop. There is no place in the video game community — or our society — for personal attacks and threats.” The International Game Developers Association also issued a statement condemning internet haters for harassment.

While the Quinn-Gjoni spat brought #GamerGate to life, the underlying revolt of the Internet and the cynical marshaling of its cleansing power has been brewing for years. It’s clear some people are frustrated because their voices aren’t being heard.

Matt Higby, the creative director for Sony Online Entertainment’s massively multiplayer shooter PlanetSide 2, told me that he had quite a long history in dealing with Internet hate. But it accelerated in the last couple of years as social media caught on in a big way. He has seen the sharp knives of gamers come out on places like Twitter, where sometimes the only really easy thing to say in 140 characters is an insult. Just as Internet mobs formed, Sony was seeking a lot of player feedback to fashion its sci-fi shooter PlanetSide 2. Most feedback was constructive, but the team found nasty messages and threats that could be better classified as harassment.

So much of it came in that Higby’s team decided to take it on with a sense of humor. Mimicking comedians, they put together a video [see below] where they read the most insulting and incendiary tweets that the team receives. The result was hilarious, and it was a kind way to remind people that developers are human and you should treat them that way when criticizing their work and games. That was perhaps one of the most positive reactions I’ve seen for dealing with Internet hate, and it is the kind of thing that will stop the hate.

“We care, so it affects us,” Higby said.

The negativity can be exhausting, but positive comments can make Higby happy for a month. The mean tweets video was aimed at showing that “we are just people, in a humorous way.”

Higby worried that we’ll see a chilling effect on developers who are fearful for joining the conversation, because they don’t want to be “doxxed,” or making one’s private information public on the Web. He says that real death threats have to be taken seriously and shut down. But he also says that a conversation has to take place.

My stand is simple and unoriginal. Self-examination is good, but the evil side of #GamerGate, like the ruination of lives it has inflicted on the small number of victims who have been skewered in the spotlight, has to stop.

Sensationalism also has to stop. The British tabloid Breitbart took a crazy tangent when it discovered a “secret mailing list” of game journalists, GameJournoPros (of which I was a member), where journalists discussed how to help victims in the controversy and take stands on coverage. Breitbart’s reports brought down that forum, which was really a great place to discuss the trade in an informal way.

Journalists should disclose their conflicts, but fans should also realize that game journalism isn’t easy and that its adherents view it as a profession, just as game development is hard to do and requires professionalism. Alternative voices should be heard, and people should be allowed to interpret #GamerGate as they see fit. No one likes it when, in an argument, someone simply denies that you have a right to a point of view.

Above all, people should stop speaking for gamers as if they were a monolithic group. They’re not. And people have to think and understand what they’re doing before they step into the s***.

The last thing I’ll bring up has caused me a lot of personal angst as the mob goes after its victims. My daughters have shown a lot of talent, and they enjoy games. I’ve encouraged them to play and to think about joining the game industry.

But if this is the way that gamers and the game industry treat its female members, I can no longer encourage them to think about a future where they would one day make games.

And that’s a shame.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More