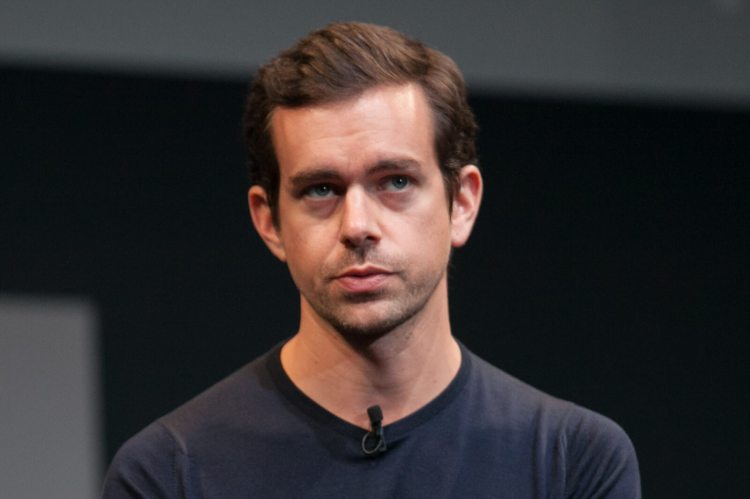

As you may have heard, microblogging service Twitter officially welcomed Jack Dorsey home as permanent CEO last week. The happy reunion has a major caveat: Dorsey is staying on as chief executive at payments company Square.

It is a Herculean task to run two companies at once, and one that few men have even attempted. Adding to the difficulty, Dorsey will need to steer Twitter out of its rut while also balancing Square’s potential public offering.

By putting Dorsey at the helm, Twitter is taking so gargantuan a risk that it begs the question: Is Dorsey really the person for the job?

The answer to that question may have less to do with Dorsey himself than with the story that surrounds him. The idea that Dorsey could lead two companies (each with their own sizeable issues) to victory is an assumption predicated on the myth that Dorsey is the next Steve Jobs.

That myth may be a fine tool for helping reinvigorate Twitter, but it also has great potential to do the company harm.

The myth

Comparisons between Dorsey and Steve Jobs are so overused they’ve become cliché. This is due in part to an oversimplification of Jobs’ legacy to fit the parameters of legend. The storied version of Jobs is that he founded a company, was forced out because of his inability to lead it, and then ultimately returned to usher in a prosperous new era.

It’s a feel-good American tale and one that is now being fitted to Dorsey. Of course, the two share some similarities: Both are known for their big product ideas and recognizable uniforms, as well as for having been ousted from companies they founded and enjoying triumphant returns. However, there are also very key differences.

Jobs founded Apple at age 21. By the time he was ousted nine years later, the company had gone public and enjoyed some success, but was in a rut. The Macintosh computer was not selling. Rather than face a reorganization in which his role at Apple would be greatly reduced, Jobs resigned. He went on to lead two other companies — one called NeXT that ultimately failed to spark interest with consumers, and another called Pixar, which became a huge success.

“He really learned from getting kicked out of [Apple] and the failure of his NeXT venture. And he learned from Pixar that he’s not the world’s smartest guy, or the most knowledgeable guy in these things, and that’s how he learned to be a team player. There’s no evidence that Dorsey has gone through that same experience,” said Michael Cusumano, coauthor of Strategy Rules: Five Timeless Lessons from Bill Gates, Andy Grove, and Steve Jobs.

Dorsey, on the other hand, started working for a podcasting startup called Odeo when he was 29. While at Odeo, Dorsey shared his vision for the platform that ultimately came to be known as Twitter. He became one of the key engineers developing the service and, in 2006, sent the first tweet. Dorsey worked his way up to CEO quickly, but resigned two years later under pressure from the company’s board, who thought Dorsey was devoting too much time to his personal life and not enough time to the company. Shortly thereafter, he founded Square, which disrupted the payments industry with its initial product: a tiny credit card reader that could be affixed to a phone through a headphone jack.

In the six years since, once-baffled payments companies have caught up with Square’s innovation and in some cases surpassed it. Meanwhile, Square has created a suite of back-office software and food delivery services for restaurants to complement its point-of-sale system, but is no longer the most innovative product in the payments space. What’s more, Square is now facing a ton of competition. Payment processing is a numbers game, and that means Square has to figure out a way to scale up its payments volume (preferably quickly) in order to grow returns. More immediately, the company is also seeking to go public.

This position is markedly different from the one Steve Jobs was in when he returned to Apple while keeping his hand in at Pixar.

“When Steve Jobs was running two companies, he had one company that was fairly stable. Toy Story had just come out and was doing really well, and so he could think about another company,” said Sinan Aral, the David Austin professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Pixar was also already a publicly traded company.

Even with Pixar’s relative stability, Jobs stayed interim CEO of Apple for three years before going full-time. Twitter, on the other hand, took a mere three months to explore its options before awarding Dorsey the permanent chief executive role.

Chief executives at two companies

Running a company is really hard; managing two is more than doubly so. Consider also that some companies are so complex they have two CEOs. Samsung, for example, has both J.K. Shin and Kwon Oh-hyun in the lead role. A rare few individuals have pulled off running two companies at once, but that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. Even Elon Musk, who leads both Tesla Motors and SpaceX, advises against it.

“It decreases your freedom quite a lot,” Musk said onstage during the Vanity Fair New Establishment Summit. Ironically, Dorsey’s love of freedom was the very thing that put him at odds with Twitter during his first run as CEO.

But, even if Dorsey has evolved to prioritize work above his personal life, there’s a high potential for him to fail both Square and Twitter.

Square

“When you think of Elon Musk, both of his companies are not in competitive industries. But when you think about Square and Twitter, you’ve got one company that’s under a ton of pressure, flagging user growth, user engagement. And then you have another company that’s about to IPO and go on a road show and is under a lot of pressure,” said Aral.

Square operates in an incredibly competitive space against both small startups and big players, like PayPal and First Data. In order for Square to be successful, the company needs to raise its total payment volume, which, at last check, was about $30 billion annually. Last year, First Data did about $1.7 trillion in third party verification (TPV), while PayPal processed $235 billion.

Adding a public offering to that scenario will undoubtedly make running Square and Twitter more difficult, and Dorsey’s split attention will not likely inspire confidence in investors.

Twitter’s problems may be slightly less daunting. The company is already public and ranks among the largest social networks ever built. It’s also showing strong ad revenue growth. However, growth of its active user base, which pales in comparison to Facebook’s, is slowing. The company needs a serious change to make Twitter more appealing to the masses. The stream of leadership changes also points to a company in turmoil.

Already, Twitter has revamped its discovery functionality and homepage to reflect trending events and has added a new section called Moments, which serves up newsworthy tweets. But there’s still a lot of work to be done. Dorsey will need to lead the company through further product innovation and helm a strong marketing campaign to convince more users to join the platform.

Between the needs of the two companies, it’s hard to see how Dorsey will be able to divide his attention. Without some give and take between company responsibilities, Dorsey may only be able to deliver mediocre results, despite his best efforts. It seems he’s set up for failure from the start.

“Jack Dorsey is really talented, but I think that the risks of doing double duty with these two companies are really real,” said Aral.

We like legends

So why is Twitter choosing Dorsey to lead the way as chief exec? Dorsey was already helping shape Twitter in his role as chairman of the board. It seems that hiring a more available CEO would have been a better option for a company in need of executive attention.

Of course, I don’t know how the board came to its decision. I’ve heard speculation that nobody wanted the job and that the board was forced to choose Dorsey. I’ve also heard the opposite — that Twitter had its pick, but that Dorsey was the best candidate for the job.

Here’s a third possibility: There were other suitable candidates, but Dorsey had the potential to bring enthusiasm to Twitter’s teams.

“We looked at many (many, many) other options. We weighed them seriously. We also discussed ad nauseam the challenges of Jack doing both his CEO jobs at once. I honestly didn’t think we’d land on Jack when we started unless he could step away from Square. But ultimately, we decided it was worth it,” said Ev Williams in a Medium post explaining the decision.

Dorsey is an underdog character in the story of Twitter — one who created something big, was denied ownership of the thing he created, and has come back to reclaim it. It’s an easy narrative to get behind, and Jack is a likable character.

“It is a watershed moment for Twitter and a watershed moment for Dorsey. If he pulls this off he will add his name to a very short list of tech greats,” said Aral. There is no doubt that everyone has their eyes on Dorsey. We’re watching to see whether he’ll take his place among the gods or fall from the sky, a sticky mess of wax and feathers.

For Twitter, the Dorsey Myth acts as a rallying cry: Don’t let Jack fail! It has the power to motivate workers and initiate the necessary productivity and creative thinking to lead the company to success. It also invites the media and investors to become a part of the cheerleading squad rooting Dorsey on to win.

The harm in mythologizing

Consider for a moment, though, that Twitter may be buying into a contrived fantasy, insisting on the myth rather than appointing someone who is available and capable of helping Twitter reorganize and push forward.

The danger of indulging in myth lies in the potential for overlooking qualified candidates who don’t encompass our ideas about what kind of person should lead a company. Myths also encourage improbable decisions. Just because Jobs was able to triumph at Apple doesn’t mean Dorsey will also succeed as a returning CEO at Twitter.

I don’t doubt that Twitter’s board had good reasons for not selecting from the myriad of other candidates that were up for consideration. But offering the title to Dorsey does seem an unnecessary risk. The company only searched for three months, perhaps a result of Twitter’s sinking stock price. Still, it could have taken more time to find a leader capable of devoting their full attention to Twitter.

If we follow Jobs’ trajectory, we see that he was interim CEO at Apple for three years (1997-2000). Jobs thought running multiple companies would be too exacting and leave little time for his family. His temporary status was largely of his own design and gave Jobs the flexibility to finish his work at Pixar without causing too much disruption to Apple. It was never his intention to juggle both at once.

Twitter talks about the “big, bold changes” that lie ahead, and recent product releases give us an inkling of what’s to come. But perhaps more compelling than any new product would have been a big, bold change of leadership.

Check out part two of this essay: Unconscious bias: How Twitter found the best ‘man’ for the job

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More