No doubt about it. October was a tough month for space enthusiasts and the world’s private space industry.

The explosion of the Antares rocket, which was headed to the International Space Station, was followed just a few days later by the crash of Virgin Galactic’s and Scaled Composites’ SpaceShipTwo space plane.

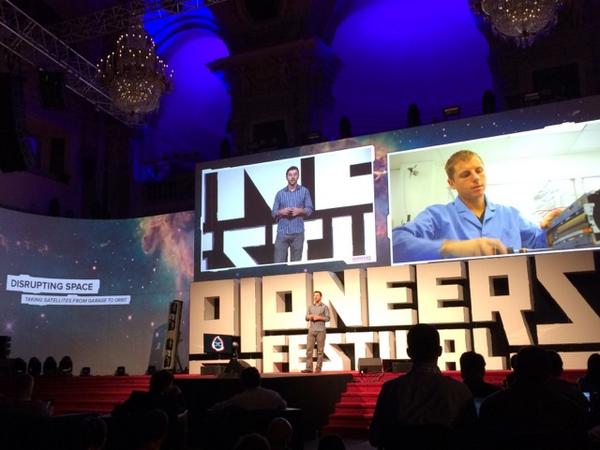

While it’s entirely reasonable to see these pair of events as a setback for the private space industry, I heard a very different view last week in Vienna, where I was moderating a discussion about space entrepreneurship at the Pioneers Festival.

My fireside chat featured Pete Worden, director of NASA Ames in Silicon Valley, and Andy Aldrin, president of Moon Express, which has planned the first private mission to the moon sometime next year or early 2016.

And speaking on stage before us was Mike Safyan of San Francisco’s Planet Labs. The company lost 26 of its low-Earth imaging satellites in the Antares explosion.

In conversations on and off stage, all three sounded a common theme: We are on the cusp of an exciting new era in space entrepreneurship.

While the conference took place before the Virgin accident, they were clear that the Antares explosion wouldn’t have much impact on the growing space economy.

“This is absolutely an exciting time for space entrepreneurship,” Worden told me. “There’s so much happening right now. And the next five years are going to be incredible. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to come here and talk about this.”

Of course, there have been some headline-grabbing space startups in recent years. Like Elon Musk’s SpaceX. And Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origins. And of course Google and NASA have been partnering with Silicon Valley companies on projects like quantum computing to help find life-supporting planets.

Space will become a big business

But many more efforts have attracted far less publicity, even as they appear on the cusp of a groundswell.

Moon Express, located on the NASA Ames campus, is just one intriguing example of NewSpace. Founded in 2010, the company has raised $15 million from private investors to build its lunar lander. Aldrin said the company will need to raise more capital, but not much more, to get to the moon.

Compared to the $1.5 billion (in 2013 dollars) it cost NASA to send a probe to the moon in the 1960s, the Moon Express expeditions will cost just a fraction. In turn, Aldrin says, the moon contains valuable resources, like rare minerals found in asteroids that have crashed there, as well as the large stores of water that the company could potentially bring back to Earth orbit.

The goal is not only to perform scientific research, but also to make this endeavor an actual business.

“It just shows you how far we’ve come,” Aldrin said, whose father is astronaut Buzz Aldrin.

Worden, in his role at Ames, sits at a kind of hub of the space economy. In addition to working at times with Moon Express, he meets with entrepreneurs who are looking for opportunities and the chance to partner in some way with NASA. The space agency increasingly is seeding these projects via contracts, contests, and grants.

Beyond space tourism

On stage, Worden mapped out a number of areas where companies are already pushing startup ideas beyond space tourism.

Starting closer to home, companies like Planet Labs (more on them in a moment) are launching low-earth satellites. And there is NASA’s project called “Cubesats,” tiny satellites just 100 cubic centimeters in size. They were developed in partnership with universities to teach satellite design, but they are small and relatively inexpensive to build, so more people can have access to the technology.

“Just about anyone is going to be able to participate in the space economy,” Worden said. “You don’t have to an astrophysicist.”

Worden also mentioned a company called Made In Space, which launched the first 3-D printer into space in September. Made in Space is planning to manufacture vehicles and structures needed for deeper space travel — eliminating the need to launch equipment from Earth.

Moving beyond Earth’s orbit, companies like Planetary Resources (backed by Google co-founder Larry Page and filmmaker James Cameron) and Deep Space Industries are looking at asteroid mining for things like minerals, metals and water. These would also provide the basis of space manufacturing and the creation of fuel in outer space to enable deeper space exploration, Worden said.

All of this, Worden said, is laying the groundwork for interstellar travel. He expects travel outside our solar system to happen before the end of the century, and for it to be driven by private companies, not public space agencies. Interest in such travel is growing, he said, thanks to NASA’s Kepler telescope, which is searching for Earth-like planets beyond our solar system.

Worden says there is a third group he expects to play an important role in the space economy: “entre-philanthropists.” There have been a growing number of billionaires, in Silicon Valley and around the world, who have expressed interest in funding space projects, like interstellar travel, though he declined to name any names.

“They don’t expect to make money from these ventures,” he said.

Still, plenty of these companies intend to be for-profit ventures, like Planet Labs. The company’s constellation of satellites is generating rich images and data that the company then sells.

It’s rocket science

In talking to Safyan a couple of days after the Antares explosion, he was distinctly not spooked by it. He explained that such incidents are not unexpected, and indeed the company built its business model and launch timetable with the assumption that satellites would be lost from time to time.

It’s certainly a reminder of the challenges inherent in working in space, Safyan said. But he said by spreading its satellites around a number of different rockets at different times, it also showed that executives were learning to manage the risks. Just like in any other business.

“It’s rocket science,” Safyan said. “It’s par for the course, even. But you just have to learn not to put all of your eggs in one basket.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More