If you subscribe to my newsletter you can read these columns a whole day before they appear on our website. All the cool kids are doing it!

Is there anything more American than a robot that can create anything you want out of a spool of plastic and some electricity?

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that 3D printers offer levels of Jeffersonian self-reliance that our founding fathers only dreamed of.

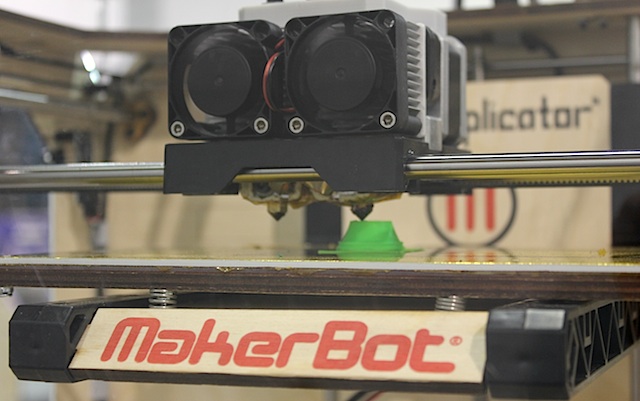

“We have a consumer product that’s anti-consumerist,” MakerBot Industries founder Bre Pettis told me at CES 2012, where I captured the short video below. “When you get a MakerBot, you have an alternative to buying things. You can download them … or you can design something and make it custom yourself.”

The new MakerBot Replicator is a $1,750 box that can print three-dimensional objects by melting and fusing bits of plastic line, layer by minuscule layer. A version that prints objects in two colors costs $2,000. It’s one of several new, affordable 3D printers that are hitting the market this year.

If you can dream it, and if you can create a 3D representation of it in an STL file, a desktop 3D printer can create it in a few hours. Provided it’s small enough, that is: The Replicator can only create objects smaller than 300 cubic inches, or about the size of a loaf of bread. Not quite big enough to assemble a cotton gin or a replacement plough blade, but certainly large enough to make toys, chess pieces, gears, artwork, cups, bowls, and a lot of other things.

“This is kind of magic, because there was nothing there, and now there’s something,” said Pettis.

Also, unlike the Star Trek Enterprise’s replicator, MakerBot can only create things in inedible ABS plastic or biodegradable PLA, so it won’t be able to make you a cup of tea — Earl Grey, hot. Sorry.

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/34923875 w=560&h=314]

Still, 3D printers are making a whole new field of creativity accessible to computer geeks. In the same way that laser printers enabled people with computers to become publishing experts in two dimensions, these printers are opening the doors to creative, computational expression in three dimensions.

I’ve been fascinated with the “do-it-yourself” movement since I went to my first Maker Faire. Subsequently I investigated the growing world of hackerspaces, where people gather to work on code, learn how to solder, teach crocheting classes, borrow a welder, slice things into strips with a bandsaw, use a drill press, or work on projects that involve all of the above skills. The MakerBot emerges from this world, as Pettis was one of the telegenic evangelists of the DIY ethic and is a cofounder of NYC Resistor, one of the earliest U.S. hackerspaces.

I’m convinced that the people who have embraced the DIY movement have tapped into the core of what makes the United States great: Self-reliance, experimentation, innovation and a non-dogmatic reverence for facts. Over the decades, innovators tinkering in metaphorical (or literal) garages have played important roles in the development of electricity, radio, computers and, now, the internet economy.

DIY, or at least a willingness to take initiative for doing things on one’s own, outside the usual structures, has also played a role in political life, with grassroots organizations like MoveOn.org and loosely organized movements like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street drawing much of their strength from people’s iconoclasm and sense of self-sufficiency.

But one thing that hasn’t emerged from the DIY movement — until MakerBot — is a major venture-backed business. MakerBot Industries might change that, as the company has now raised more than $11 million in investment capital and employs 75 people in its Brooklyn headquarters. Not only that, Pettis told me the company has openings to hire another 30 people. He didn’t say whether the company is making money now, but he did point out that Makerbot did about $8 million in revenue on its seed round investment alone, which was only about $75,000, so the business has promising roots.

What about competitors?

One of the biggest players in the 3D printing space to date has been Shapeways, which VentureBeat has covered previously. Shapeways lets designers print objects not only in plastic, but in ceramic and metals as well, and it allows you to print larger objects than you can with the MakerBot printer. But you can’t buy a Shapeways printer; you upload your design to the company’s site, and it ships you the finished product. Shapeways, by the way, counters my assertion that DIY product-printing is an American phenomenon — the company was founded in the Netherlands. But its $5.1M funding came partly from New York’s Union Square Ventures (the rest came from Index Ventures in London), and the company has now moved its headquarters to New York.

Another ship-to-your-door 3D printing company is Sculpteo, which I also ran into at CES. Sculpteo prints in ceramic.

But when it comes to consumer 3D printers you can have at home, MakerBot’s main competitor seems to be 3D printing pioneer 3D Systems. I spent some time at CES ogling the company’s Cubify Cube printer. Cubify prints plastic objects in different colors, and has a more clean, iPod-like industrial aesthetic compared to MakerBot’s hacker-y, DIY aesthetic. The Cube is also cheaper, at just $1,300. (Check out our video of the Cubify below.)

Pettis’s response to the competition was cheeky geek macho.

“Our machine makes things that are twice as big as their machine,” Pettis said.

And that’s another really American thing: Competition. Let’s hope it helps make 3D printers cheaper every year, until everyone has one of these strangely anti-consumerist consumer devices in their own kitchens, right next to the breadmakers.

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/34885455 w=600&h=337]