Twitter is broken. Facebook you can’t trust. Google+ is a wasteland.

And Ello? Well, if you can get past its monospaced font, aggressive rejection of color, and beta-stage bugs and incompleteness, well, Ello is pretty nice.

Over the past month it’s become clear that most of the tools we use for communication and community online — our social media networks — are broken, either by design, or because they have outgrown the purposes for which they were built.

This is the dark side of what used to be called the “attention economy.” The more people (or corporations) require our attention, the more they will invade those areas where we happen to be paying attention. On Facebook, that means advertisers. On Twitter, it’s trolls.

As a result, any person or conversation can be a target for trolls in proportion to how popular she (or it) becomes. To get attention, they go where the people are.

Nothing makes this clearer than #GamerGate, a ridiculous argument between hardcore gamers and video game journalists that overspilled its banks last month and turned into an uncontrolled, seemingly endless, metastasizing free-for-all.

As David Auerbach writes in Salon, GamerGate shows that on Twitter, “the line between discussion and harassment is slippery.” Because conversations happen in public, anyone can drop in at any time and make your conversation theirs. If 100 or 1,000 of their friends subsequently drop in to the conversation too, you can no longer be heard. The crowd shouts you down.

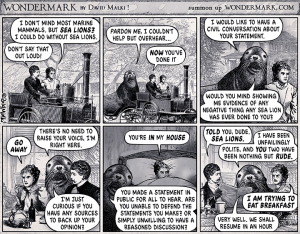

Worse, this “conversation” then overtakes your entire experience of Twitter. The problem was satirized in a cartoon by David Malki that, Auerbach notes, has since been adopted as a kind of touchpoint by GamerGate participants themselves.

If you enjoy Twitter, and use Twitter extensively, it becomes a kind of “social sixth sense,” as Clive Thompson called it back in Twitter’s early days. That sense makes Twitter become an extension of yourself, which at first feels awesome.

But when the whole world — including people you find obnoxious, loathsome, or who are outright aggressive towards you — suddenly shows up inside this “sixth sense,” it feels invasive.

The people who are harshing your mellow have a point, though, just like the sea lion: Anything you say on Twitter is a statement made in public, for all to hear.

GamerGate didn’t invent the obnoxious, public flame war, of course. Trolls have been on the Internet since the days when Usenet ruled. “Doxing” (looking up personal information on a person and publishing it) as well as sexual threats and harassment have been an unfortunate part of Internet culture for a decade or more.

Kathy Sierra, an early Internet marketing and product development guru, was driven off the Internet in 2007 by harassment, including death threats — the kind of treatment that is now unfortunately routine for any women making controversial statements in public or semi-public roles online. It wasn’t just that people were saying mean things to Sierra; she received threats that made her fear for the safety of herself and her family.

Sierra has recently returned to the Internet and posted a thoughtful, heartfelt piece about trolling. It should be required reading for anyone concerned about community and conversation online. (Also worth reading: The response from Andrew “Weev” Auernheimer, a troll who Sierra — and several journalists — identified as one of the major sources of her harassment. Weev’s response is both a retort to Sierra and a pretty clear statement of his own character and motivations.)

As Sierra points out, you can’t win in a fight with the trolls: The game is stacked in their favor. But she ends her post on a hopeful note, suggesting that it might be possible to create better alternatives:

I do think we need more options for online spaces, and I hope one of those spaces allows the kind of public conversations and learning we had on Twitter but where women — or anyone — does not feel an undercurrent of fear watching her follower count increase. Where there’s no such thing as The Koolaid Point. And I also know the worst possible approach would be more aggressive banning, or restricting speech (especially not that), or restricting anonymity. I don’t think Twitter needs to (or even can, at this point) do anything at all. I think we need to do something.

Maybe one of those spaces is Ello. Right now, it feels like the kind of hopeful, civil, wonderful experiment that Twitter did in 2007. Maybe it’s the ethical social network we all need. I’m not a deep enough user of Ello to know why exactly it works better, but it certainly seems like a different, healthier kind of place.

I don’t know if that’s something inherent in the design of Ello, such as its lack of advertising, or if it’s just because Ello is still small and the trolls haven’t started to arrive yet. I suspect it’s the latter.

My theory: Any sufficiently popular conversation is eventually owned by those who value attention the most.

Am I wrong? Are there technologies or design patterns that can prevent this from happening? I sure hope so. Let me know what you think.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More