On Tuesday, Enish will make its debut on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Enish is a mobile gaming startup; its largest customer is Gree. In U.S. markets, such an IPO would be laughable; mobile games are apps or even features here, not legitimate, sustainable businesses.

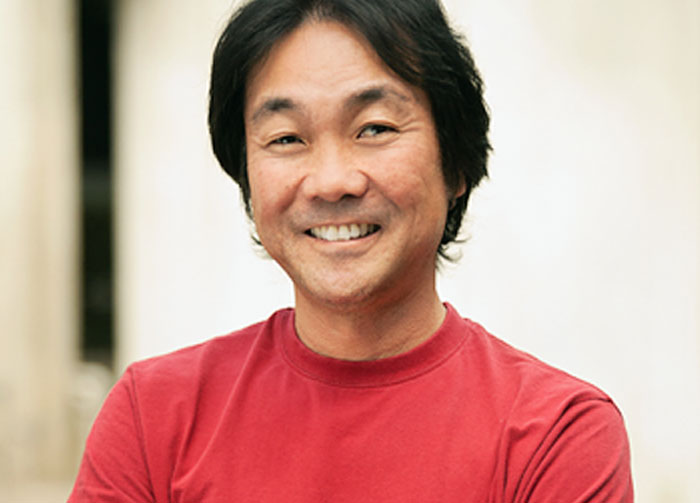

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":586225,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,mobile,","session":"A"}']But, as one of the company’s earliest investors, Masanari Arai, pointed out in a visit to VentureBeat’s offices yesterday, the mobile-only IPO has been around in Japan since the dotcom days, when 20 or 30 startups went public based on HTML content for feature phones.

And even nowadays, a company can create a simple feature like emoji for SMS and turn it into a $15 million monthly revenue stream. In the U.S., such a business model would be laughable at best; no VC would take the company seriously.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

So what’s the difference?

“People in Japan are waiting to pay. U.S. people are not,” said Arai. “That’s the big difference.”

A lot of the willingness to pay involves the delivery mechanism, says Arai, as well as expectations and habits developed over a decade or two of widespread network and Internet access.

“People in the U.S. started to receive Internet services on a PC browser, and they didn’t have to pay for anything,” said Arai, referencing the now-ubiquitous brand- or ad-supported web and mobile ecosystem in the States. “People just expect everything for free.”

But, he continued, “In Japan — and China is the same way — the Internet didn’t start from the PC. It started from the mobile phone. In 1999, email — people were not doing email. Normal people, housewives and teenagers, they didn’t do email. … Dokomo set it up where you had to pay 300 yen a month for email. It was common sense.”

Dokomo, Arai said, pioneered the charging mechanism that is the sole reason Enish’s IPO works: micro-payments billed to the carrier with a single button-push from the user, starting in 1999 with feature phones. These small transactions, usually less than 300 yen and usually recurring on a monthly basis, have to be insignificant enough that the user never thinks too hard about deciding to make the purchase and never questions the activity on his monthly statement.

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":586225,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,mobile,","session":"A"}']

In aggregate, the equivalent of $1 or $2 per user over ten or twenty or thirty million users — that’s the start of a real business.

“One dollar, people don’t care. Once they’re signed up, they’re happy and never think about if they’re overpaying,” said Arai. “One or two dollars is a very, very sweet spot. If you’re asking for $50 or $100, people start asking, ‘I’m paying this much money, for what?'”

But the scheme only starts with the price point; after that, you have to maintain a constant and creative cycle of new releases and fresh content to justify the monthly subscription.

“If you have a fixed function … it is very difficult to change your mind to paying every month; you’re not getting new stuff every month,” said Arai. “When we create mobile services, we always want to charge the user every month. It’s recurring revenue, you have a steady stream.”

And while in the U.S. we find it harder to get people to pay for mobile services than for computer software or even web services, Arai’s perspective from Japanese and other Asian economies and cultures is the reverse: “Monetization for PC services is pretty tough because therer’s no charging mechanism.”

[aditude-amp id="medium2" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":586225,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,mobile,","session":"A"}']

When he puts it like that, it makes total sense.

“If you compare PCs and mobile devices … my strong philosophy is that mobile can replace your PC,” Arai continued. “Most of the tasks, you can do it. You can get a whole solution in your hand that you carry all the time. I grew up in that environment, starting in 1999.”

Arai’s career began and flourished in the heady era when the web was still finding its legs and laptops were still a novelty. He himself was a product manager for IBM’s first ThinkPad.

“ThinkPad started in 1988, the concept started,” he said. “The movement from the entire desktop to mobile devices: This was the start of mobile. It was a revolution, and [the devices] just started to shrink and shrink and shrink.”

[aditude-amp id="medium3" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":586225,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,mobile,","session":"A"}']

But while being at the forefront of one revolution — personal computing hardware — was a thrill, Arai said he got his biggest kicks out of another revolution: the bubbling ecosystem of startups, investors, and entrepreneurs in Northern California.

“Silicon Valley was so exciting compared to IBM,” he said. “People just decided immiediately; at IBM, everything took six months. So I decided to quit IBM and join a small startup company.”

That company was Intellisync; it made an app for syning data between mobile devices and PCs — a feature now so commonplace thanks to companies like Google and Apple that we don’t even think about it. But in 1999, it was quite forward-thinking; at that point, the company had gone public and was named stock of the year.

The aftermath of that was a typically tragic dotcom fractured fairy tale. “Our stock started at $2 and went to $200,” Arai said. “In 2000, it started crashing, and in 2002 [the stock price] was 40 cents.” The company survived long enough to be acquired by Nokia in 2006, providing Arai with his next big career move.

[aditude-amp id="medium4" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":586225,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,mobile,","session":"A"}']

But even Nokia, then a champion in the blossoming mobile world, couldn’t keep Arai content. “I don’t like large companies. I became a company manager for Nokia, but it was too big. I just wanted to start a new business — that was 2007.”

So Arai founded Kii Corporation, an investment firm and services company with deep roots in the mobile-first worlds of Asia and an unwavering emphasis on mobile companies. In recent conversations we’ve had with U.S. investors, over and over again they have refuted the idea that a mobile application can be turned into a large and legitimate business fit for anything but a quick sale. Kii Corp. offers the opposite thesis, and since it works in markets where that makes sense, it prospers.

Enish will be Kii Corp’s first initial public offering. Arai has known its founders since around 1998. The company’s CFO and CEO also have a history of mobile success; the duo did their own IPO in 1999 with a fortune-telling app for feature phones. “Their valuation was something like $100 million at that point,” Arai said.

Enish will make its debut on the TSE’s Mothers market, a special sub-section of the exchange for emerging and high-growth startup company stock. Mothers was established in 1999; at that time, it made sense to have a sandbox for the highly visible and volatile offspring of the web and mobile boom. The Mothers index has dropped significantly since its inception, but its roster of companies has grown to 178 as of October 2012. The number of Mothers IPOs per year has also risen steadily over the past few years from four in 2009 to 13 this year.

[aditude-amp id="medium5" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":586225,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,mobile,","session":"A"}']

As our interview ended, I wished Arai luck on Tuesday’s offering, but something tells me that decades of experience in mobile revenue, hardware revolutions, dizzying IPOs, failures, acquisitions, and friendships have prepared Enish’s first investor for this deal far beyond any need for good fortune. Luck, if it favors Arai, will be mere icing on the cake.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More