Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

OP-ED — You would think by the reaction some are having to it that Facebook’s recent admission that it experimented with some people’s feeds is tantamount to Watergate.

You would think there had been some terrible violation of privacy or a breach of confidential user data. Instead, 700,000 people read a slightly different version of their news feed than the rest of us.

Here’s what happened: Over the course of a one-week period back in 2012, Facebook altered the balance of content in the news feeds of 700,000 of their users. They showed some people more “positive” content while others saw more “negative” content. According to the published paper, “Posts were determined to be positive or negative if they contained at least one positive or negative word, as defined by Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software.”

The goal was to determine what (if anything) would happen to these two groups. Would they express more positive emotions after seeing lots of positive content? Would they express more negatives ones if the opposite were true? In short: Could their subsequent behavior be seen as “a form of emotional contagion.”

Now you might think that in order to elicit a really strong and measurable set of reactions, Facebook inserted stories of small children being abused or an especially adorable set of cat videos. After all, if we were going to be mad at Facebook it should be because they showed us content we wouldn’t have otherwise seen, in an attempt to screw with our emotional state, right?

But that didn’t happen.

Or at least, it might have, but Facebook didn’t create that shared content. The friends of the 700,000 unwitting victims participants created it.

That’s right. Facebook merely adjusted the balance of content these users would have already seen if they looked at each and every one of the items their friends had shared over the one-week period.

“But how could they do that?” I hear you say. “I never agreed to be part of such an ‘experiment’.”

Actually, you did. When you signed up for Facebook. And if you’ve been a member for more than a few months, I guarantee this was far from the only time Facebook has done it.

In fact, apart from the specifically emotionally oriented and highly organized nature of this experiment, almost every website worth its salt has performed similar tests.

Editorial publications will try out different approaches to their content to see what gets readers to click. They’ll try straight-up reportage styles that state the facts and nothing but the facts. They’ll try emotionally charged headlines. They’ll even imitate the Buzzfeed style — you know the one: “You Won’t Believe The Epic Thing This Guy Did Right Before This Happened.” If you’re like me and you tend to throw up in your mouth every time you read one of these digital come-ons, you can thank the testing that went in to discovering that formula. It didn’t happen by accident.

According to Wired’s David Rowan, “If there is a science to BuzzFeed’s content strategy, it is built on obsessive measurement. The data-science team uses machine learning to predict which stories might spread; the design team keeps iterating the user interface through A/B testing and analytics.” You can read the full article here, though be prepared for more eye-openers.

So if this kind of thing is happening all of the time — and make no mistake, it is — why are people so upset by Facebook’s emotional A/B testing?

I can only assume it’s because people found out.

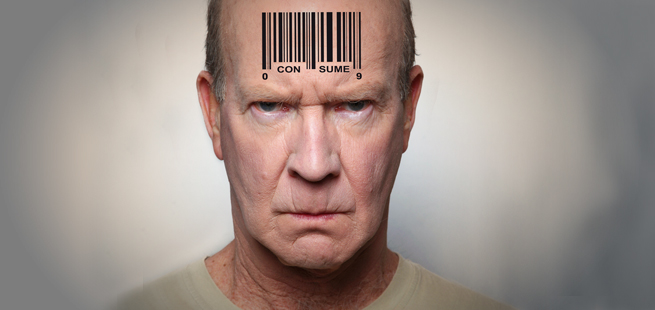

We don’t like the idea that our every move online is being studied, effectively turning us into digital guinea pigs. That’s a pretty reasonable reaction to have when you have a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Which is why the realization that Facebook was tracking its users across multiple websites through the use of the their ubiquitous “like” button even when the user was logged out of Facebook, came as a shock.

But Facebook’s experiment happened on Facebook’s own site, while its users were logged on, and only presented material posted by other users—specifically the friends of the users being studied. Where exactly is the expectation of privacy under these conditions?

And yet, it’s precisely for violations of privacy that Facebook is now being investigated.

Here’s how the Financial Times summarizes it:

The company’s policy did not explicitly disclose that it used personal data in research studies, […] the company had said that it used data “in connection with the services and features we provide”, without specifying research.

So even though the research in question was all about better understanding how its users interact with “the services and features we provide,” apparently they need to state that such research is happening. Good grief.

I suppose our municipalities must now inform drivers that they might be subject to research when they use city streets. After all, how else could we decide where new traffic lights should go?

Here’s a little advice for those who are still feeling that Facebook has once again manipulated them and ignored their privacy: Get over it. This kind of testing is happening all over the web and in real life too.

The negative content that was populated into people’s feeds came from their friends. The positive stuff too. All Facebook did was re-organize it. Did you know you could do the same? There’s a little drop-down arrow beside the News Feed menu item – simply switch it from Top Stories to Most Recent.

And if you’re still bummed out after reading a week’s worth of negative crap? Don’t blame Facebook. Blame your friends.