A gaming studio can easily pay 10 times its development budget on acquiring players, and the frightening truth is that companies are flushing a lot of that cash down the toilet drain.

Marketing fraud extracted $6.3 billion from developers last year, and Singaporean publisher GoGame says developers should only work with publishers that understand that problem. Speaking at the Casual Connect conference in Singapore last week, GoGame chief executive officer David Ng explained that mobile studios desperate for new players are often paying for bots instead. With Clash of Clans maker Supercell and Candy Crush publisher King spending $500 million on advertising each, player acquisition costs are already sky-high. For a developer to survive in the $36.9 billion mobile gaming industry, they need to minimize the harm of fraud.

Gaming on iOS and Android thrives on free-to-play apps with virtual items that sell for real money. Developers know that they can count on a certain average lifetime value (LTV) for each person who installs their product. If the LTV is $25, developers often pay $24 to acquire a player because they’re still going to make a profit. Some companies, like King, are even paying more than the LTV because they know that each person who installs their game will tell a friend or two who are also worth $25.

To attract these player, developers and publishers work with advertising networks and other firms to “acquire installs.” Typically, a studio agrees to pay a certain amount for each install these networks bring in. Often these network will then work with all kinds of other companies that have ad inventory. It’s these groups that create those ads that force open your iOS App Store or Google Play market when you visit a mobile website.

This is where the fraud comes in. The networks are paying a fee to anyone who brings them an install, and these smaller advertising groups are sometimes using bots to download games over and over that no one will ever play.

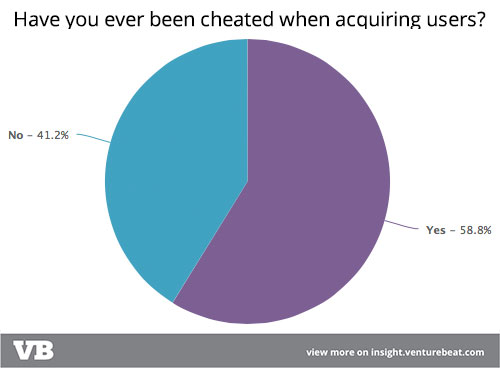

Above: A survey from early 2015 suggests a lot of marketers know about this problem.

“Faurd exists, and the industry knows it,” said Ng. “It has to do with tracking. When you see the outliers, it’s obvious. But most people can’t spot the outliers. We can accept when the tracking makes some mistakes. But when it gets to 30 or 40 percent fraud — that’s too much.”

Ng says that while most people in mobile gaming are aware of the problem, many don’t understand it. Fixing the problem will require publishers to fully investigate how fraud happens so that they can spot it and cut off networks that let it happen.

“If a single device has 500 to 600 clicks on the App Store, someone is messing around here,” said Ng. “This is what you’re paying for. You’re paying for bots to download your game.”

Ng went on to explain some of the ways that publishers and developers can spot trouble, and a lot of the solutions will involve paying closer attention to data most studios already have. One example is looking for discrepancies between where you’re getting the store clicks that you’re paying networks for and the data downloads.

“When you get thousands of clicks in the states but all of the downloads are coming from the Philippines, you need to know how to protect and how to prevent this from happening,” he said.

Of course, Ng thinks the best solution is for developers to work with a company like GoGame. For now, he probably has a point since a publisher paying attention to fraud like this is better than one that wants to brute force their way through it with larger marketing budgets. The goal, however, is to get to a point where even the smallest studios have the tools they need in their Google Play developer dashboard to avoid fraud on their own.

Casual Connect arranged for my travel to its event. Our coverage remains fair.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More