It’s the latest company to ride the wave of enthusiasm around crowd-sourced funding, a trend sparked in part by the recent JOBS Act legislation.

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":513991,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,","session":"B"}']However, the JOBS Act hasn’t been promulgated yet by the SEC, and the company is actually taking advantage of a different regulation, the little-used Regulation A, which lets you do public offerings under $5 million.

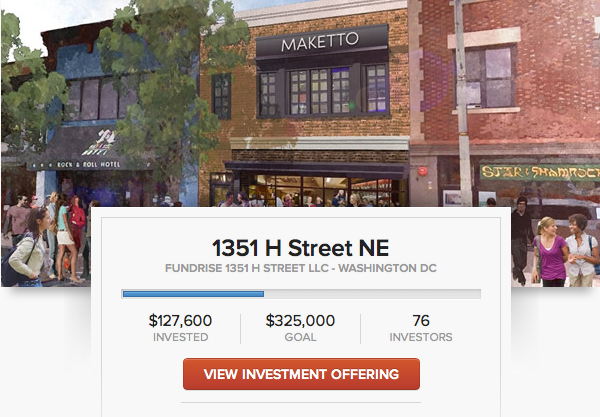

Fundrise launched last week, with the goal of raising $325,000 for its first offering, a property at 1351 H Street, in Washington DC. It has already raised $127,600 from more than 60 investors, co-founder Ben Miller told me.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

Another part of the company’s vision is to let community residents partake in neighborhood development projects they care about, he said.

It’s Simple

The beauty of this Fundrise is how it cuts through oodles of red tape to get such deals done. Indeed, Miller says the reason he launched the company is because of the hassles he and his brother, Daniel Miller, had with their existing real restate business. They were forced to raise money from private equity investors, often complex deals. Moreover, these investors had few ties with the communities they were investing in, and their interests were often unaligned.

Another elegance to Fundrise is that there are no middlemen, and that all investors are treated equally. If you invest $100 in a property, you have the same economic stake in the investment as the general managers of the deal themselves, i.e, folks like Miller. There are no “preferred share” versus “common share” differences, where one class of investors gets a slightly better deal than another. There are no liquidation rights. No first-out clauses. No broker-dealers. It really looks like the real deal. The only difference is that so-called “Class A” shares are owned by the managers of the deal, who have a few more governance and voting rights, as you might expect. Class B shares have the same economic rights, but no governance rights.

How is this possible?

Miller tells me the company had to work really hard to qualify the offering with the SEC and register it with the securities regulators in Virginia and the District of Columbia. The idea for company actually started two years ago. It took his team eight months to get through the regulations. They even hired the guy who wrote the original Regulation A documentation in the 1990s. Surprisingly, when Miller was researching deals that were filed under Regulation A last year, he found only 22 filings, only three of which ended up being registered. In other words, the opportunity had been sitting there, vastly under-utilized.

But it’s not like anyone can do this. Here’s how it works: Miller and his team at Fundrise had to first use their own money — made in from prior real estate business — to buy the 1351 H Street property outright. That took up-front cash. They then turned around and used another site they’d built, called Popularize, to gather public opinion and input about the property. The found that there was local interest in high-end food market. So they leased the property out to the creators of fashion company DURKL and Asian food Toki Underground to combine the fashion and food concepts. The space is now being renovated for a hybrid food and fashion market called Maketto. The money raised will be used to pay for the renovation and the interior infrastructure for Maketto.

According to the company, each share purchased entitles individual investors to a percentage of the Maketto holding company, which owns:

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":513991,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,entrepreneur,","session":"B"}']

- Shares of ownership in real estate property (1351 H Street NE)

- 30% share of potential profits of Maketto

- Rights of ownership (Investor Benefits exclusive access to events, discounts, gear)

There are other perks, too. A $100 share gets you access to things like shareholder events and cocktail receptions. If you buy $1,000 in shares, you get extras like a 10 percent discount on all food at the new market, and some Limited Edition DURKL Maketto gear. And for $10,000, you get an annual food and wine dinner prepared by the food company’s chef.

On the face of it, Fundrise looks to be doing everything right. The only thing limiting it is the ability to scale. It is only available for now in Washington DC, and Virginia, and it’s got a ton of work ahead of it to expand into other markets (it has to fight through local regulation red-tape), and it also needs to raise money fast to afford to buy other properties that it can put on the platform. And of course, there’s still the large, established REIT industry, where investors who aren’t hung up on making specific investments in their community, can already make real-estate investments. Two questions remain: How compelling will community real estate investing really be for people? And will others beat Fundrise to a larger play nationally?

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More