But even as we willingly record and share more of our lives, the issue will inevitably spring back to life again. As the balance of costs around sharing versus keeping things private change, there must be some set of expectations attached to what we withhold and why.

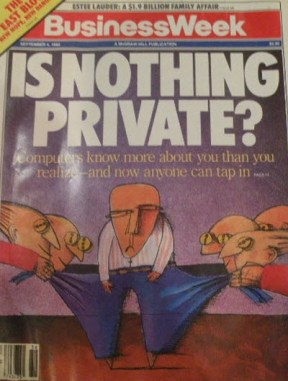

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":153357,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,social,","session":"C"}']Privacy is a notoriously difficult term to pin down. The word itself stems from the Latin privatus, which means to separate or deprive from public, and privare, which means to bereave. In an American context, the value of privacy has been historically linked to liberty and freedom from government interference. (I also wrote a shorter related blog post on privacy in the context of Facebook’s business model too.)

Some definitions of privacy focus on keeping parts of our lives separate. Privacy is about controlling what others know about us. It’s “the state or condition of being withdrawn from the society of others, or from public interest; seclusion.”

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

Others definitions include an actionable element — privacy is about managing what others know and whether they can act based on that knowledge. It’s “the state or condition of being alone, undisturbed or free from public attention, as a matter of choice or right; freedom from interference or intrusion.” (Both of these definitions are from the Oxford English Dictionary.)

- If we start from a definition where privacy is about information and control of it, then it’s probably safe to say that privacy is dead or on its last legs — unless people stop using the web and credit cards wholesale.

- If we start from a definition where privacy includes an actionable element, then we can have an interesting discussion about frameworks for the future.

Why do we demand privacy?

This seems like a dumb question. But when the costs of sharing decline relative to withholding information, we should reevaluate our assumptions. The question facing us every day is moving from “Why would I share this?” to “Why would I keep this private?”

Privacy is a way of managing multiple identities and their contradictions: A phrase Facebook likes to trot out publicly is that it’s the place where you can be your “authentic self,” as COO Sheryl Sandberg has said in the past. But multiple social networks like Twitter, Facebook, MySpace and LinkedIn have co-existed because we have many authentic selves. There is a self I present to my boss, a self I present to my family, a self I present to the public and one for my closest friends. They’re all different, authentic and they often contradict each other.

That notion is supported by a growing body of psychological research that shows that character isn’t ingrained or even coherent. Rather, our personalities are the sum of competing tendencies that play out differently depending on the context. Identities and contexts used to be separated by physical space. There was college and your parents’ house, the office and the bar, the restaurant and your bedroom. Now, identities are a click or Web site apart.

Naturally, people don’t like to conflate these identities. (It already takes a great deal of cognitive dissonance to live them ourselves!) You wouldn’t want your boss or colleagues who know the responsible, upright version of yourself to know the version that stays out late on Friday nights.

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":153357,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,social,","session":"C"}']

The need for privacy is also about recognizing that our identities change over time. We don’t necessarily want to be judged or held accountable for a poor decision we made 10 years ago.

Privacy is about physical safety: This one is fairly intuitive. It’s why people are reluctant to reveal their home addresses and why location-based networks like Foursquare and Gowalla that use a temporary “check-in” system have steamed ahead of persistent location-sharing ones like Google Latitude.

Privacy is about preventing falsehoods or lies from being spread about us: There are two parts to this. One is the older concern about libel or slander and that our reputations might be harmed. Since libel laws for the web are nowhere near as strict as they are in print, people have found the best way to manage their reputations is to be aggressive about having an online presence. Buy your domain, claim your Twitter handle, your vanity Facebook URL and foster a community that you interact with constantly. The other is the emerging concern is about identity theft. I’m less knowledgeable about this, but encryption, smart passwords and keeping your identity in a basket of services rather than a single one would go a long way.

And a new need — protecting our corpus of data from unforeseen applications: The atomic bits of data we leave around the web amount to little on their own. But taken together, they form a corpus of data that may reveal our motivations and desires. Companies could end up making conclusions about us that we didn’t originally intend to share or that are outright false. Credit-card companies already do this, punishing people with higher-interest rates if they frequent bars or stores that other less credit-worthy customers patronize. And that’s even if their credit history is clean. In a social networking context, it could mean mining friend lists or profile view data to predict hook-ups or whether someone is gay (which a few MIT students actually did).

[aditude-amp id="medium2" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":153357,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,social,","session":"C"}']

Two ways at looking at the future of privacy

Everyone has privacy because no one has privacy. This looks silly at first glance. But if you think about it, the more data we share about ourselves and the more contradictions we reveal, the less people may collectively care about any of them.

Consider Obama’s admission that he tried cocaine in his autobiography and during the presidential campaign. This would have been unthinkable 20 years ago. Remember Bill Clinton hilariously saying he smoked, but “didn’t inhale” during the 1992 campaign? The next generation will see the first presidential candidates with their full adult lives recorded in social media — everything from the embarrassing drunk pictures to their stellar accomplishments. Perhaps we will become more forgiving and accepting. Society as a whole becomes more tolerant of people’s faults and inconsistencies. And in a benevolent world, data mining helps companies better anticipate and serve our needs.

This is a more benign view, but it also involves a radical redefinition of privacy. Privacy becomes less about what people know, and more about about their ability to act upon that information. A reckless photo from 10 years ago? Social norms evolve so that it becomes a faux pas to fire you on the back of them. More health data becomes shared? Laws arise so that insurance companies have less power to discriminate against you based on genetic misfortunes or maladies.

[aditude-amp id="medium3" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":153357,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,social,","session":"C"}']

We’re seeing elements of these changes already. The Federal Trade Commission has been holding hearings about behaviorally-targeted advertising and weighing whether interest-based ads should be labeled online. Google and Yahoo have also both released dashboards showing how they target you. (Their conclusions that I’m interested in ‘Technology’ and ‘Finance’ almost seem too innocuous to believe given how much data they have.)

The Panopticon is now used as a metaphor for power by those who can gaze over those who are watched. In a new era of ubiquitous cellphone cameras and sensors, people are aware that they can be monitored at any time. Ironically, the web could end up being more of a conformist force because we moderate our behaviors knowing that our lives can be recorded and searched.

The web also ends up reinforcing old power structures as those with the financial and technical resources to do intensive data mining (the Ivy- and Stanford-bred management, workforce and investors of tech companies) hold power over those who casually share data. Behavioral tracking and constant optimization of user interface design and advertising not only allows these companies to satisfy our desires, but influence them.

[aditude-amp id="medium4" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":153357,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,social,","session":"C"}']

Although I think social norms will also become more lax, I lean toward the pessimistic view. We’ve only seen the beginning of what machine learning and data mining techniques can make possible from what we share.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More