The freedom to be invisible

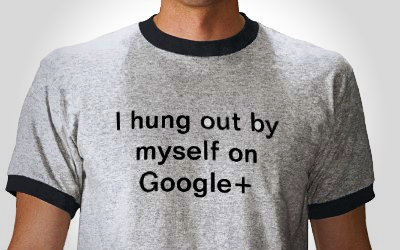

But what about those of us who lurk, who don’t want to be social, who prefer a web of information rather than interpersonal connection?

But what about those of us who lurk, who don’t want to be social, who prefer a web of information rather than interpersonal connection?

I count myself in that number. When I search, I don’t want to see links my friends liked. When I look at a map, I don’t really care where others have gone.

I ask Horowitz whether Google+ as part of all Google products means that I would be forced to be “social” whenever I use any of Google web services.

“Certainly, some products like Google search will support ‘incognito’ mode,” he tells me, outlining the three ways I could use any web product: unidentified, identified or pseudonymous.

“All three modes have different values to the user and different product implications,” says Horowitz. “Not every product will support all three modes. Something like Google Checkout is the highest bar, where financial processes are involved. And there’s a spectrum in between. Some products make sense to support in multiple modes, and it’s sort of a product-by-product decision.”

Ultimately, Horowitz says, the company’s goal is to give you the freedom to be who you want or need to be in any given moment.

“Blogging, for instance … is an important service on the Internet. That’s one that warrants having pseudonymity and having support for those use cases,” he says.

The issue of handles or pseudonyms is at the crux of Google’s approach to profiles and identity. In Google+’s infancy, your “common name,” that is, the name your mama gave you, was the only identifier you were allowed to use for the product. Your “StonerGuy420” username from YouTube wasn’t going to cut it; the company was insisting on real names for “real” identities.

However, Google has shifted its stance on pseudonymity and will be allowing users to flow between anonymous, pseudonymous, and identified use of its products.

And as far as sharing is concerned, Google is deliberately making sharing a little more difficult than it is on other services. “We think in contrast to existing solutions, we want to give you clarity, transparency and choice,” Horowitz says.

“We’ve introduced friction into sharing quite deliberately. We want people to see, who gets this? Is this the right decision? We want to bring that cognitive load to the foreground … We want users to be thoughtful and deliberate about these things, and we’ve made that trade-off.”

Google responds to critics

In the face of rampant criticism over waning usage of his product, Horowitz says, “I never thought I’d be sitting here after Halloween with the usage we have. It’s delightful; it’s an amazing situation.”

In the face of rampant criticism over waning usage of his product, Horowitz says, “I never thought I’d be sitting here after Halloween with the usage we have. It’s delightful; it’s an amazing situation.”

Is he reading the same Internet we’re reading?

A September study showed a 40 percent drop in public posting on Google+, while a widely circulated study from last month said that visits to the service peaked quickly then dropped by 60 percent.

Then there’s the anecdotal evidence: Users taking to Facebook and Twitter to throw stones at Plus.

But again, Horowitz et al. are not looking at the trees, a.k.a., public posts and hangout activity. They’re looking at the forest, and so far, they like what they see.

“When we look at engagement, we look at how often those users are coming back to Google, and they’re coming back all the time — for search, to look at maps, to read email,” Horowitz says.

“Our engagement is extremely high, and this isn’t rhetoric. This is going to manifest in the products themselves.”

The Google+ team isn’t too concerned with emotionally weighted keening from tech pundits. “It’s relatively easy to filter out the diatribes and rants,” says Horowitz. “What’s much more seductive are the accolades and the praise.”

In the service’s early days, after all, “We were lauded as the saviors of the open web,” Horowitz reminds us.

But now, he and the rest of the team choose to absorb words of praise and understand the relevant criticism. Horowitz here paraphrases a dictum from Google co-founder Sergei Brin: It’s not that you shouldn’t listen to what people say, you should also watch what they do.

“A lot of our decisions are based on the clickstream in addition to sentiment analysis,” Horowitz reveals. “You’ve got to have a little window for stuff to come in. You’ll miss a lot of great feedback if you slam the window shut.”

For example, Google originally required gender to be visible on users’ profiles for Google+, a decision Horowitz says was “a deliberate and pro-user choice” to make sure users had the best possible understanding of who was in a given space.

“What we heard back was that the right of users to decide for themselves trumped that need,” Horowitz says. “That came from a lot of user feedback, people said they didn’t want to share their gender with everyone. So we flopped and we reacted and we changed the product. If we had been tone-deaf, we wouldn’t have made that call.”

And as for the rest of the critics, Horowitz concludes our talk on an arch note: “Nothing I say is going to impact the immense curiosity about our products and the rampant speculation about our imminent success or failure. And that’s ok. We have a clear inner compass and long view.”