Search engine leader Google has started offering a universal profile for any user of Google products, in its latest effort to become a social network.

Search engine leader Google has started offering a universal profile for any user of Google products, in its latest effort to become a social network.

However, the move is risky because the feature tries to define who your friends are for you, using data Google has collected about from your usage of various services — without giving full control over who gets to learn what about you.

In short, this is not social networking. It’s creepy. Creepy, because Google has so much information, and is encroaching in other parts of our lives in a awkward way — when many of us it mainly as a great research tool.

The profile is currently available on Google Reader, Google Maps and Shared Stuff (more here). It publicly displays your name, your photo, and other information that you can edit.

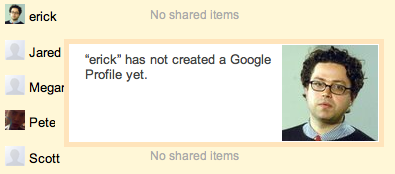

The profile also includes a list of people gleaned from Google Talk and Gmail Chat. Separately, people you chat in Gmail are automatically added to your Google IM list — then your “friends” list. Google’s calculation is that the people you chat with are your friends. (See screenshot below the article.)

These people can see more information about you, such as where you work.

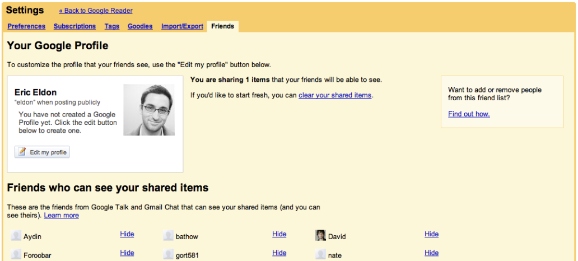

Last week, for example, Reader came out with a new social feature which lets you see articles that other people are reading (see screenshot). If you go to “settings” in Reader, you can click on a “Friends” tab and see your Google profile as well as your Google-defined friends.

These people aren’t necessarily my friends. For example, one Google “friend” is Erick Schonfeld, co-editor at Techcrunch (a rival blog). He and I have had an IM chat or two but I don’t even really know the guy. At least for the time being I don’t want him to know what stories I’m sharing via Google Reader. Of course, I can remove him from being a Google friend. But, what if I hadn’t noticed he was a friend, in the first place?

These people aren’t necessarily my friends. For example, one Google “friend” is Erick Schonfeld, co-editor at Techcrunch (a rival blog). He and I have had an IM chat or two but I don’t even really know the guy. At least for the time being I don’t want him to know what stories I’m sharing via Google Reader. Of course, I can remove him from being a Google friend. But, what if I hadn’t noticed he was a friend, in the first place?

Google is wrong to build in such assumptions about who is friends with whom.

The structure of relationships contained in social networks is what makes them valuable — not just the mass of data. Google can’t automate relationships. If it wants to build social networking into its applications, it should focus on helping people create those relationships.

Otherwise, the evidence suggests Google is headed for trouble. Even though many people are becoming less concerned about online privacy, as illustrated in this new study by the Pew Internet Project, 85 percent of adults still say it is as important as ever to control who has access to your personal information. The report notes that this statistic has held steady for many years.

Currently, the company doesn’t clearly explain how it knows all this stuff about you in your Google profile, or why it connects you to certain people. The only two Q&A’s currently in its FAQ are:

Who can see my Google Profile? Anyone can see your Google Profile. When you post publicly, your nickname (and not your full name) is shown to people viewing your content.

Can people do a Google search for my name and find this profile? It depends. If you put your full name in the “Nickname” field, pages on which your profile appears may be returned as results by Google.

Wait, did I ask for a Google profile in the first place? Do I want people to see this information about me in Reader, Maps, or wherever? Why can’t I just opt out of all of this?

Nevertheless, the company has apparently started implementing some of this information in Orkut, its social network that somehow got huge in Brazil and India but not many other places. If you want to invite friends from Gmail, you don’t just get an invite list — which is how every other social network invites people from your email accounts — you get to see their Gmail profiles.

Social networking is about giving users control over their relationships, then doing innovative things with that data.

With Facebook, for example, you get to decide who your friends are and what they know about you. Don’t want to be friends with somebody? Don’t accept their friend request. Don’t want to share all of your information with them, put them on a “limited profile” setting, that restricts them to basic information about you.

The site carefully massages your sense of relationships. For example, only people in a physically oriented network of your choosing (such as “Silicon Valley,” “San Francisco” or “Oregon State University”) automatically get to see your full profile.

Its a difference of founding roots, and philosophy, maybe. Myspace, the largest social network in the world, grew out of the LA cultural ferment. It started by bringing together demi-celebrities like goth bands, professional wrestlers and pornstars, and their fans. Then it became a place for those fans to hang out with each other. Facebook grew out of college dorms. As Jamie Zawinski famously said: “Your ‘use case’ should be, there’s a 22-year-old college student living in the dorms. How will this software get him laid?”

Google, however, doesn’t seem interested in helping 22 year old college students meet their idols or get laid. It just seems to want your data. Why?

It needs massive amounts of data to analyze, to help it deliver more contextually relevant information to you in search results and advertising. The blog Google Operating System has a post that goes into more detail on this.

Marissa Mayer, Google’s vice president of Search Products & User Experience, in this interview:

People should be able to ask questions, and we should understand their meaning, or they should be able to talk about things at a conceptual level. We see a lot of concept-based questions — not about what words will appear on the page but more like “what is this about?” A lot of people will turn to things like the semantic Web as a possible answer to that. But what we’re seeing actually is that with a lot of data, you ultimately see things that seem intelligent even though they’re done through brute force.

Peter Norvig, Google’s Director of Research, in this interview:

I have always believed (well, at least for the past 15 years) that the way to get better understanding of text is through statistics rather than through hand-crafted grammars and lexicons. The statistical approach is cheaper, faster, more robust, easier to internationalize, and so far more effective.

Dear Google: You may be the best engineers in the world, but it will take a feat of social engineering for your social networking efforts to work. Please be more sensitive.

[Reader,] I know what you’re thinking: “Andy, what’s the big deal? This is information that you’re already sharing anyway!” I know, and I’m really not looking to opt-out….yet! But, do you know what Google has planned for Google Profiles or shared items? Do any of us know? All I know is that it’s a little worrying that a company that has access to all of my data, won’t give me an off switch. [ Give it another ten years, and this is what will play out…

Andy: Google, I’d like to stop sharing my information with the world.

Google: I’m afraid I can’t let you do that, Andy.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More