Once upon a time, Rubicon Development had been scratching a living doing contract work for various clients for several years. It put food on the table, but it was hardly a commercial easy street, and the work itself was usually uninteresting jobs we wouldn’t have picked given the choice. Such is the life of contract developers – you take what’s offered because that’s all there is.

Great Little War Game

Developer: Rubicon Development

Publisher: Rubicon Development

Release date: April 27, 2011

Platforms: iOS, Android, PlayBook, PC, Chrome OS

Number of developers: 5

Budget: £120,000 [about $190,000] (Game and tech)

Length of development:

About 12 months

However, one hot summer’s morning back in 2009, I realized I just didn’t want to go to the office that day — or for the rest of the year, for that matter. OK, everyone gets days like those, but you know there’s a real problem when you don’t want to go and work at your own company. I mentioned this to my business partner and found he felt exactly the same.

Just having that brief conversation polarized us. We would finish the current job, which Murphy’s Law of course dictated would be our biggest and longest, and then we would stop taking new work in and go indie — no matter what.

We didn’t make a business plan; we didn’t even decide right then and there what we’d make or for what platforms or any of that stuff. We simply knew we had to go indie or shrivel up and die (of boredom).

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

As we reached the end of that last work-for-hire gig around February 2010, Apple’s App Store was becoming a serious draw for us, and by the time we were ready to make a start, we’d decided that’s what we’d specialize in. Android gaming showed imminent promise, too.

That just left picking a game to make. This was actually pretty simple, as my favorite handheld game of all time was Advance Wars for the Gameboy Advance. It became a classic, so obviously there was a market for those sorts of games, and because I’d played it to death I knew where I could make a bunch of solid improvements to the formula.

And that was that. We hoisted the indie flag one day and never looked back.

What went right:

Independence

There is only one piece of program code in the entirety of Great Little War Game that’s not written by us, and that’s a public domain ZIP file loader.

In my view, to be truly independent, you have to not just get out from under the thumb of a publisher or other controlling body but also avoid being beholden in other areas, too, such as tools and technology. To that end we wrote all our own game-specific tools and tech: renderers, animation systems, sound engine — the works.

In the indie world where time really is money, this probably sounds like madness to a lot of people, but because of this ethos, we can write games quicker than most, as our tools have been designed to work the way we do and we understand them forward and backward. We can also fix bugs the same hour we hear about them, without waiting for a middleware provider to “get back to you.” As you’ll see later, this was important.

But most of all it just feels like it’s all our own work. When I point at Great Little War Game and say “our studio made that,” I really mean all of it. This may not have any importance from a business perspective, but it’s why I write games and not banking software — it’s important to me.

App Store spotlights

We released Great Little War Game on iOS only to begin with. Back then, the whole Android scene was pretty new, and we didn’t have the staff for two major jobs at once regardless.

Anyway, within a few days of release we got a front page New and Noteworthy feature from Apple. We didn’t know anyone there or any of that stuff; they just plucked us out of nowhere. As a new nobody studio with an unknown brand and zero track record, we hadn’t even had that “what if” conversation in the office, so you can imagine we were ecstatic to see the feature show up when it did.

I’m sure this was more luck than judgment (probably 100/0), but this feature turned out to be vital to our company, as those first few days of sales beforehand were looking truly grim. Had we not had that feature, I’d probably be keeping my nose down in Barclays’ IT department by now and not writing this.

We’d designed our tech to work in a platform independent manner, but we’d still not gotten around to making the game run on Android yet, so this was our next task. A few months later we had that box ticked and rolled out our first ever Android game.

And boom, another featured spot. We couldn’t believe it.

And then some time later, Google hit their magic 10 billion downloads milestone and included Great Little War Game in its big promotion for that as well. If anyone wants to know the true power of PR, get Google to do an announcement with your name on it. Although we were only making 10 cents gross on every sale, we were shifting about 400 copies a minute for almost 24 hours. That netted us about £20,000 [about $32,000] in a single day. If only they were all like that!

At some point later on, we ported the game to Blackberry Playbook. And sure enough … you get the picture.

I think in the whole history of everything, the attention Great Little War Game got from the platform holders was beyond our wildest dreams, and we’re eternally grateful to them. We would not be in business today without them.

Look and Feel

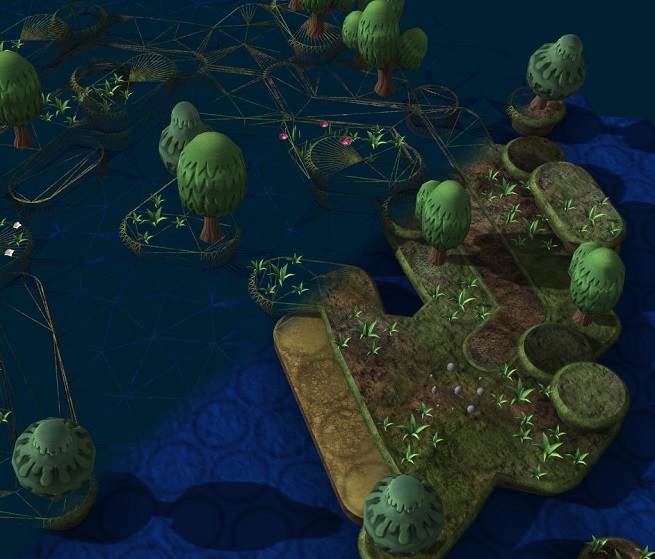

It will come as a surprise to nobody that Advance Wars was our main inspiration. We had a bunch of new ideas to put in, but the first difference anyone sees is in the display, so we had to bring that up to modern standards.

Maps: We wanted to go with hexagons for gameplay, as diagonal movement in square grid-based games just doesn’t work properly. The problem here, though, was that this is much harder to make map geometry for – you can’t just line up a load of squares or cubes because the hex shapes intersect with each other and it looks awful. We solved this by writing our own tool to extrude 3D meshes from height-difference contours found on a 2D tile map that the designer could lay out quickly.

Performance in-game was also a key issue, so we had to ensure these meshes were uniform manifolds without intersections and overdraw. This processing takes ages even on a beefy PC and is the sole reason we’ve not put a map editor into the actual game, despite many requests for it. (The reason we didn’t supply the PC tool to do it is that it’s buggy and not written with the player in mind. I still feel guilty about not addressing this.)

Men and machines: We needed a fairly unique style to make the game stand out and we discussed many ways to go with drawing the units. The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker was the aesthetic I had in my head from the beginning, but then our artist showed us “Choro Q,” a Japanese toy line sold in the West as “Takara Penny Racers.” We were all instantly sold on the big rounded look and took that styling to the world of tanks and armor.

Game controls: We thought long and hard about how the game controls should work – or more specifically how the viewpoint should work. The control method was always going to be “tap and drag,” as that’s what touchscreens were invented for.

We tried putting the camera down among the action, like you see in a first-person shooter, and this made for some excellent-looking screenshots. The problem with that though was it made the game much harder control. Gameplay always comes first, so we binned this idea completely and went with a bird’s-eye view for the main display. Later on, we made the camera zoom in on fights as they play out which gave us the best of both worlds.

Presentation

If you’ve played it (if no, why not?), you’ll see right away that we went for a quirky and irreverent air throughout, as we didn’t want the game to be taken too seriously.

We pick up some occasional flak for the thinness of the unfolding “story” running through the game, but most players realize this was deliberate. I have a particular dislike for games trying to cram a story in where none is needed, so this was our jibe at all that. I think on balance we got it right — but we didn’t clearly 100 percent nail it.

Also key to this irreverence was the music. We had to keep this upbeat and jaunty whilst still sounding like a military march, and again that went perfectly. We have no in-house audio capability, so we had to contract this out. Luckily, the very first person we tried turned out to be extremely good and understood our needs perfectly. Most of the audio in the whole game was done in one take.

Show me the money

Great Little War Game has been out on various platforms for a little over two years now. The Android and iOS versions are by far and away the best performers, and between those two formats they’ve earned us about half a million dollars. It might surprise many to see that Android isn’t that far behind iOS, which goes against the grain of much perceived wisdom in the trade. Android is great!

- Total earnings to date, iOS: $283,760.53

- Total earnings to date, Android: $216,424.23

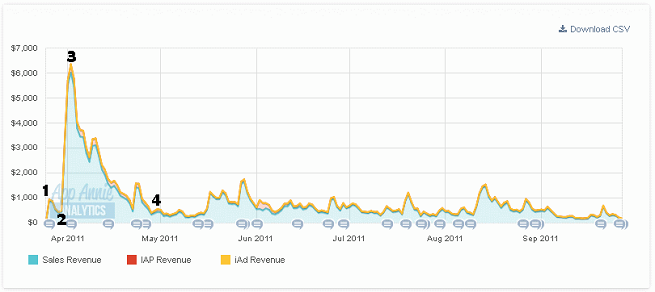

You can clearly see the effect of our New and Noteworthy and the rather telling figures just before it. I didn’t include more time in this image as the remainder of the sales graph just looks like a cut and paste of the rightmost inch of this one, but even less high. The “long tail” on mobile seems long indeed.

I put some interesting labels on for you.

- Launch day

- When we nearly quit mobile development and filed. Just two days in, initial sales had more than halved to about $400, with no indication of putting the brakes on by tomorrow.

- Salvation! Can you spot when the new and noteworthy started?

- Interestingly, this is where it ended. Back then you got a month in the spotlight, losing prominence each week along. To be frank, I do find it a bit depressing that most of our sales are based not on game quality but on how easy it is to find and tap an icon.

The bad news for us is that before we switched to mobile development and began Great Little War Game, we had been stitched up by a former client we did a lot of that contracting work for. We’d lost our personal savings and got into some debt and had even got to the point of phoning the tax man for clemency on our mounting unpaid bills.

When that first mammoth post-feature paycheck came in from Apple, my biz partner and I took most of it straight back out and used the money to dig ourselves out of our respective financial holes. It saved our business, and our homes, but we were left in a state where there still wasn’t much new money coming in after the feature period had expired and sales settled down to a background level.

There were five people to pay out of all this, three of us in the office and two contractors on a backend royalty deal, and the income just about managed to pay us all a living wage, barely. Not exactly an auspicious start to our new business, but we’d basically made it and decided to continue onward to see what the future would bring.

After we’d launched on Android, we got to the point where we actually had a workable income and didn’t live in permanent fear of having to close next month. And that’s about where we’ve stayed right up until time of postmortem. There are no Ferraris in our car park, but we can at least stand proud and say we operate a viable small business in a very challenging marketplace. That makes me happy.

What went wrong

Poor budget planning

As I hinted at above, we were in a financial mess when we started development of Great Little War Game. Not only did we not have a budget for the development itself, we actually owed other people money, mainly the tax man. I’ll bet not many developers start a project with negative capital!

So we did what we had to do, decided to get hung for a sheep instead of a lamb and went further into debt. Our company wasn’t worth a dime as collateral for a loan, so this involved us staking our very livelihoods on the line by remortgaging our homes. That’s not to be recommended and is hardly sound business advice, but it certainly brings a level of focus that you can’t get any other way!

I’d make a clichéd analogy about a tightrope walker without a safety net at this point, but a more accurate description would involve also throwing away the balance beam and the tightrope!

So, that’s us — we at least had what we thought was enough money to get the game done and dived right in to make it happen. We all had a very clear vision of what we were making and things went fine for a while, but by the time we got to halfway through our budget, we realized we’d not gotten halfway through the development.

Due to how we got the first lot, there was going to be no more money, period. That led to a few crisis meetings where the inevitable decision finally got taken – cut unstarted features, rush the remainder, and just ship the game before we all starve. This is never a good thing, but it was a double blow for us because one of the reasons we wanted to go full indie was to get away from compromising our creations and doing silly crunch development at the end.

Buggy, rushed launch

Leading on from the above panic sprint finish, I’m sure it will come as no surprise that the game we initially shipped had almost no QA (Quality Assurance) work done and was therefore extremely buggy. Even our Apple feature became a double-edged sword because the public was buying the game in droves, which meant a day or so later all the Internet forums started lighting up with delightful stories about what a crap game we’d made.

And there were some real howlers in there, too, things you’d think the developers should spot even without a dedicated QA focus. Like the fact that the only iPad the game ran on was ours. Or the fact that you had to do level five in one sitting else it would autosave itself with an immovable obstacle stuck in your path.

These were not good times, especially for someone like myself with decades of experience making games. Of course with the beauty of digital distribution, we got all of this stuff fixed and updated in fairly short order, but the damage to our reputation had been done. We looked like rank amateurs.

We’d also made another fatal mistake related to the product launch and that was not budgeting any time or money to do some marketing. Even when we acknowledged that the pot was running dry, that budget was always designed to last just until we pressed the button on the store.

We should have been pushing the game in the press and forums and such long before we shipped it, but we just didn’t have the time. After shipping, when some advertising might have helped, we didn’t have the money. In fact it’s fair to say that Great Little War Game wasn’t actually launched at all but simply cut loose.

No multiplayer

This one isn’t really a mistake of its own because when we got to that feature-cutting stage, this is the main one we had to cut. We did so because it just wasn’t physically possible to get it done in time, even if we stopped everything else, so it was never going to happen whether we wanted it to or not.

But having said that, you can’t release a war game with no online component, either. People expect it, and we doubtless lost a lot of sales because we didn’t provide it.

We actually started adding this back in for our first big product update, but it got so complicated with needing our own cross-platform servers and such,that we took the decision to save it for the sequel and a fresh budget – more on that next week.

No marketing or PR

The five core people who made Great Little War Game are all seasoned professional developers, able to boast about a hundred years of experience between them. That’s frankly ridiculous.

However, as a publishing company we have all the marketing skills you’d expect of five nerdy developers: i.e., none at all. Even despite the fact that we ran out of time and money to make some inroads here, I’ve so far glossed over the fact that we wouldn’t have been able to anyway through utter lack of knowledge.

If you want a classic example, this postmortem can be considered a PR activity, and it’s taken me over two years to get around to writing it. If any more PR-savvy person can point to something we did right during our launch — and I can’t think of anything offhand — I can assure them it was a complete accident!

We’re fully aware that we should have a little black book full of magazine editors’ contact info and so on, but I just don’t know how to go about getting them. I don’t feel comfortable making these kinds of cold contacts, as any advance I might make is going to be blatantly transparent and self-serving, and I’m just not pushy enough. Here’s what I’d read if someone did it to me, right before I pressed the add-to-spam button.

“Hello <database_entry>. You don’t know me, but can you give me your details so that I can abuse you in future and get you to sell my stuff for me?”

Hands up anyone reading this who hasn’t thought the same? I know it’s wrong, but I just can’t get past it. Which means this is a mistake we’re bound to repeat over and over. (I do hope game consultant Brian Baglow isn’t reading this.)

We plugged this hole in the future by retaining a PR consultant to handle our game launches, which is the best we can do. If nothing else, first do no harm!

Other format time-wasters

We wasted a lot of time trying to get the game out on PlayStation Vita. It took about four months of development time to get the game running, which seemed reasonable, but then the paperwork and other expenses started.

Four months after that, we realized we weren’t even close to meeting all these pointless hurdles and just gave it up. We simply didn’t see the benefit of making a video of an uninterrupted play session through our 20 hour game or to pay to get the Finnish review board to give us a censorship rating, or for that matter to pay a translation service to do the Flemish upsell page. (I can’t remember the actual details offhand, but that’s indicative.) Oh, and now you’ve done all this guys, you can’t sell it in America because there’s no multiplayer. Thank you and goodnight.

In hindsight it was a smart move to stop when we did, but better still to not have wasted eight months of precious development time at all.

We also got involved in the proto-Chrome Web Store that was just opening at the time. Google covered the cost of us getting the game working in JavaScript by a third party, who did very well out of it. However, we haven’t seen a penny in profit, so this was another time-waster.

Because we had a PC build working, we tried to sell that also. Steam wouldn’t even return our e-mail, so we ended up placing the game with a few well-known portals such as Arcade Town and Big Fish. Those sites are great in their own spheres, but Great Little War Game just isn’t the sort of game their typical customers want, so this proved another waste of time for us.

Conclusion

Despite those many “opportunities to improve” at the start, we’re pretty proud of what we did here. We didn’t make it big, and we needed some luck to make it at all, but we did at least make it. And given the crippled start we gave ourselves, that’s no mean feat. I think we even learned from some of those mistakes. …

Paul Johnson is the managing director and cofounder of Rubicon Development and was also the project and programming lead for Great Little War Game. Since his games industry debut in the 1980s, Johnson has spent the intervening years predominantly getting wider.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More