Jackson: One of the things I noticed at the conference here—I think we’re talking about two industries a lot of the time. There’s the traditional industry and then the digital industry, which is mobile, Facebook-oriented, driven by the analytics equation.

I just urge entrepreneurs to take on the lean startup culture. Try to seek out those methods. I truly believe the legacy industry doesn’t have a lot more going for it, unless you’re at a big studio. Most big studios are internal. It’s very hard to take entrepreneurial action in that area. If you’re specialized as an artist or a game designer, you can get hired into a large studio structure, but if you really want to participate in the newest wave, bringing in the startup culture, the culture of early stage company development — a very holistic approach to having all the pillars of good management and good business sense and good advisors – is important.

It was said many times these two days – are you making a product or making a company? I think you need to focus on making a company. This comes from 20 years in the industry, nearly 20 years.

Buttler: The real buzzword in Silicon Valley these days is not “big data” or anything like that. It’s actually “pivot.” Whenever things don’t work so well at a company in some way, it’s still cool, because they’ll pivot. It used to be, “Oh, I was wrong.” Now it’s, “Oh, we’ve decided to pivot.” That happens all the time. It’s a positive word now. I’m glad that’s the mindset, because it means, “We’re trying things. We don’t believe our own story, necessarily.”

If you look at Kabam, or even Zynga, and all these other guys, they did pivot and pivot and pivot. They didn’t even come from the gaming space. They let opportunity drive them, not their own story. That’s a tremendous strength an entrepreneur should have, to be able to pivot and find new opportunities, new things that people who have their knowledge from the old world won’t find, because they’re not listening carefully to opportunity.

Baverstock: On a related note in terms of understanding your business, a lot of games developers come at it from the point of view that they’re making a piece of art. They’re making something they care about. They’re passionate about it. They believe that if they make something great, people will share it and enjoy it with them.

There’s a fundamental fallacy there. People have to know about your product. I would encourage all small companies, all entrepreneurial teams in the industry, to engage with marketing as a function. Your marketing team and your game design team should be almost the same thing, and marketing should be as important to you, as a concept, as the game design you’re working on. There are very few developers who are that happy to engage with marketing in that way, but I think it’s very important that they do.

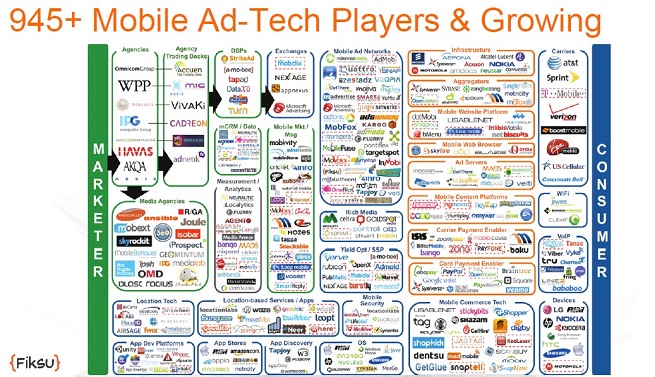

GamesBeat: Somebody had that slide elsewhere with all the ad tech companies. They showed that there are 945 mobile ad tech companies now. That seems a little nuts, but it also seems to address the twin problems of monetization and discovery that everyone is trying to solve. What do you think about the opportunities in that space? How should people sort through 945 companies?

Baverstock: I don’t think there are any easy ways of solving it right now. One of the most interesting things to watch in the industry is that discovery problem. If it starts to be solved, our industry will change dramatically again.

One of the core features of our industry right now is that nobody outside of the old-school console/retail space has a good discovery solution that works reliably, repeatably, and scalably. If we do come across that, that will tend to empower the big existing players with deep pockets against the currently disruptive small creative teams. The industry will change dramatically if a reliable, repeatable, scalable solution to discovery comes about. Today there isn’t one. It’s the Wild West. Try some stuff and see what happens.

Buttler: I completely agree. One of the reasons the mobile messenger companies get these tremendous valuations—If you look at Line, or WeChat in China, or even Facebook, which is now working on mobile as a marketing platform, it all has to do with app discovery being completely broken. The App Store and Google Play are similar to Yahoo in the old days of the internet, where the entire search engine portal was basically just listing links of the cool sites on the web. That was the initial discovery model, before Google and others came in, and now we have a completely different paradigm.

Once we have a better app discovery paradigm for the mobile web, we’ll have a mega-revolution. We’ll also take off this other 30 percent, which you never had to pay on the web. The fact that Google and Apple can control this entire environment today—HTML5 and other tools for the mobile web haven’t really taken off. It’s a pity. But nothing in the history of technology ever lasts forever. This situation where you have two gatekeepers for the entire market facing all the disruptive forces in the world has never sustained itself. Things will change. We’ll have a mobile internet eventually and that will catalyze a lot more creativity again.

GamesBeat: What do you recommend as far as the size of a mobile game studio these days? How many people should it have? How many people should be on a team? How much money should it initially raise?

Audience: This is a question to sort of answer Dean’s question about the size of mobile game studios, which is something I think about quite a lot. I think there’s a size that’s the right size for the current industry, which is something like 10 or 12 people. There’s a size that’s huge, which also works well. I worry that there’s not a good way for mid-size studios to exist right now, because 30 people tend not to make a game — Double Fine is probably an exception to the rule – that’s three or four times better, or monetizes three or four times better, than a game from a 10-person studio. The burn just tends to be much higher. I’d be curious to hear, along the lines of Dean’s question, if there’s any way to solve that problem in the long term.

Jackson: There’s the Supercell example, at a conceptual level, which is that you have to look at yourself as an incubator that’s working on multiple titles. If you’re a 30-person studio, you have to see that as five or six small teams that work quickly, that fail fast, and that you can move people around so you’re not losing a company culture, not losing investment in people. We haven’t exploited the incubator/accelerator model. It’s not necessarily about incubating small companies, in the same way that it’s done in other parts of tech. But I think there’s an application for creating games that hasn’t been found yet.

Baverstock: To pick up on that question of scale, 10 or 12 is great if you’re talking about a real startup, taking risks, trying something out. If you have an existing business with a reasonably successful game and you’re trying to make sure it’s a resilient longer-term business, you don’t want to keep those kinds of risks. Having 30 or 40 people in your studio might not make you a game that’s four times as valuable, but it will make you much more likely to deliver a good game. If you can afford that higher burn rate, you are trying to get yourself to a more reliable, longer-term situations.

It’s all about that difficult second album, right? It’s all about trying to go from something that worked – being as small as possible and doing as many games as possible – to locking it in and starting to build your audience and your community, and not continuing to take those same risks, if you can afford it.

Editor: The following is some introductory material about each investor:

GamesBeat: Please introduce yourselves.

Guillaume Lautour: I’m a partner at a VC firm based in Paris, IDinvest Partners. We’re investing around Europe, and we’ve recently invested in some companies based in the U.S., on the west coast. I’m a steady investor in two game studios. I’ve founded seven game studios up until now, all based in Europe. Some of them are still very tiny, seed-stage stuff. We do seed investments as well, as little as half a million, up to later-stage investments in companies we’ve seeded already.

We have companies like Social Point, for instance, 200 people based in Barcelona and France — they’re successful on Facebook – as well as four or five other different studios. Most of them were originally working on Facebook games and switched to mobile about a year ago.

Lars Buttler: I’ve been a serial entrepreneur and investor. I’ve started three companies in my life. I think I can relate to anyone who’s trying to raise money and build something. Before my last startup, I was at the Carlyle Group, which is the world’s largest private equity firm. Now I’m at Madison Sandhill, which is a VC in Silicon Valley, on Sandhill Road.

Right before this I actually started a gaming company and raised almost $500 million in a combination of equity and co-development and debt. That, for gaming, is not too easy. Then I started this VC company.

I’m very happy right now to look at many different things — big data, gambling even – but gaming is still a big passion. I’ve already made my first few investments in gaming. I’m very interested to see what’s going on in Europe as well, since I grew up in Europe. I have a special interest in what’s happening here.

Marc Jackson: In my current iteration I’m an angel investor and one-man incubator. I’ve set up six companies in the video game industry in the last five years, where I invest a small amount of money and provide advisory services. They’ve all been in games. One of them is Big Red Button Entertainment, which is doing the current Sonic Boom title. That took about four years to incubate, and is now a very large 70-person studio doing a console game in Los Angeles. I also helped incubate a company called Fearless Studios, set up in late 2010, which got sold to Kabam in 2012.

I advise investors, and I’ve been a specialty structured project finance risk manager and evangelist, bringing film and television style financing to games, which worked quite well in the mid-2000s. It may have a resurgence now with new business models, and I’m looking at doing some of that. I’ve also been involved in spearheading and setting up two gamification-type projects, one addressing e-learning and another addressing energy efficiency.

I have a diverse set of interests, and I’ve worked very closely with founding teams at a very early stage to set up primarily game-focused companies. I’m also a French citizen. I earned my MBA at HEC in Paris, and I have a great love for France. I hope to be doing a lot more business here.

Ian Baverstock: I’m at Tenshi Ventures in the U.K. My background is very much as a games developer. I started as a developer in 1989, with my colleague Jonathan Newth. We built that company up into a 300-man U.K.-listed company, sold it a couple of times, and did very well.

We’re now very much interested in helping other small companies get off the ground. We’re seed investors. We’re looking at the angel space, rather than large amounts of money. We like to get involved with the companies we work with and add advice as well as cash, in fact particularly the advice. You need their passion and energy, but sometimes you need the wise old gray-haired person in the corner saying, “No, don’t do that. Do something else instead.”

I also do some work with the U.K. government on the innovation side and in creative industry strategy. But here I work with my games background. That’s all.

John Stokes: Prior to being a venture capitalist I was a moderately successful entrepreneur in Asia Pacific for about 12 years. I had experience in mobile, in startups starting mobile, and then starting in internet and finally in media. Our fund is based out of Montreal, primarily investing in Canada, but doing a few North American investments, and we’re not averse to looking at European opportunities.

We are really a web/mobile investment firm, but we have been dipping our toe in the gaming industry, and because of our base in Montreal, we’re doing more. So far we’ve invested in one studio out of Toronto called Massive Damage. We’ve invested in an accelerator/incubator out of Montreal, Execution Labs. We’ve also invested in a couple of peripheral gaming companies. One is a player acquisition company out of Vancouver, and we’ve also invested in a hardware Oculus Rift competitor as well.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More