Disclosure: The organizers of the Videogame Economics Forum paid my way to France, where I participated in a couple of sessions on the game business. Our coverage remains objective.

Game investments and acquisitions have exploded in the past few years, with billions of dollars at stake. The deals, IPOs, and investments that grab the headlines include the $2 billion Facebook acquisition of Oculus VR, the $1.53 billion SoftBank investment in Supercell, and the $7 billion IPO of King Digital Entertainment. Those deals reflect the potential of games to grow into a $100 billion business worldwide across all platforms by 2017, according to a forecast by game investment bank Digi-Capital.

With such huge deals, it’s easy to get overly excited about the opportunities in games. So we discussed the topic at the recent Videogame Economics Forum in Angoulême, France (which has a video game university and is home to a giant comic book festival). In our chat with a group of seasoned game investors, we tried to sort through the hot trends and the pitfalls to avoid when investing in games.

Our session included Guillaume Lautour, a partner at IDInvest Partners in France; Lars Buttler, managing director of Madison Sandhill Capital in Silicon Valley and former CEO of Trion Worlds; Marc Jackson, CEO and founder of Seahorn Capital Group in Los Angeles; John Stokes, venture capitalist at Real Ventures in Montreal and board member of the Quebec Venture Capital Association; and Ian Baverstock, founding partner of Tenshi Ventures in the United Kingdom.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

GamesBeat: What are some hot trends that you care about right now?

Lars Buttler: The smartphone is the winning platform at the moment. What you can do with it is the interesting question. One of the things I’m looking at is whether the smartphone could be the micro-console. Everyone makes games for the smartphone, but how about using the smartphone and still playing on a great monitor or TV with a controller, a keyboard, whatever you want? In my mind that’s one of the interesting next frontiers.

Lars Buttler: The smartphone is the winning platform at the moment. What you can do with it is the interesting question. One of the things I’m looking at is whether the smartphone could be the micro-console. Everyone makes games for the smartphone, but how about using the smartphone and still playing on a great monitor or TV with a controller, a keyboard, whatever you want? In my mind that’s one of the interesting next frontiers.

Also, anything that gets us out of the super-broken app discovery model that we’ve discussed already. Is the mobile web coming back in any way? How about messengers that allow you to find apps? That’s something I’m looking at. [For example, Kik is actually the largest messenger in North America now.] It’s bigger in the U.S. than WhatsApp.

I just put some money into an equity-based crowdfunding company. After Oculus Rift, everyone is much more interested in getting a little piece of the action, not just a T-shirt. At the end of the day, though, I’ll still only invest if it’s a fantastic team, if they know how to make great games and how to monetize and make all these other pieces come together.

Marc Jackson: One of the key trends that’s affecting the games industry, especially on the digital side, is data analytics. We’re only at the tip of the iceberg, the very beginning of seeing how powerful analytics can get. Even the biggest players – Google and Facebook and so on – haven’t found out what they can do with that special mix between humans and data and the way they’re interacting with new devices.

That has a big bearing on games, because games tend to be the type of media that can be adjusted the most quickly and monetized the most quickly. I’m following some companies. For instance, in L.A. there’s a company called Ninja Metrics that’s doing some very interesting things with predictive analytics around the social graph, especially with non-paying players, that then drive players into the whale/minnow/dolphin zone. I’ve heard of some other very interesting companies here that are experimenting with bringing cognitive analytics to games. That’s a huge trend.

A lot of people are hedging their bets and watching Facebook very closely. They seem to be the one to watch. Oculus Rift is clearly going to be something that could be a leader. There’s multiple potential competing platforms, but we’re going to see some very interesting content plays. Bringing that home to Angoulême is important. Angoulême in France could play a key role in developing some alternative types of content.

Ian Baverstock: I’ve heard quite a few developers recently starting to talk about automatically adjusting their game design and gameplay based on analytics. Suddenly there’s a whole conversation going on amongst developers about how to use analytics in a realtime way, to have the game adjust — obviously this is usually A-B testable live service games – in a way where you have automatic feedback. There’s some interesting tech in development there.

If you’re looking at investments you’re always trying to figure out how to get your money back out again. How are you going to realize this investment? One of the things that’s really hot right now is this money in Asia, looking for a way to take the businesses and the cash that are there and grow those businesses, often in Europe, as the place where there’s the least development intersections.

Those companies, more often than not, are looking for companies who’ve demonstrated expertise.They expect these companies to be profitable and well-run, but they’re focusing very much on companies that have an audience, a community, and know how to engage with them. That’s something you can buy and transfer into a bigger entity in a positive way. If you can build companies in that direction, in that particular area of interest and axis of expertise, that makes you very sellable.

John Stokes: There’s a couple of similarities with some things that other people are saying here. We’ve made, as I said, a wide range of investments across the internet space, and one area we’ve invested quite a lot in is also predictive analytics, as applied to some of our other companies. We’ve done a lot of e-commerce investing, also ad tech investing, and both of those businesses are very much driven by trying to build predictive models of who it is that you should be selling what products to, who you should be promoting what services to. Using predictive analytics and those types of engines and applying it to the gaming industry is something I’m quite interested in.

Oculus is an obvious example of this, but as there are new inputs and outputs, looking for companies in the gaming space, and not just the gaming space, that are looking to take advantage of these new inputs and outputs—Oculus is one, both in input and in output. But we’re also looking at motion as an input. Touch screens and these types of things have completely changed the way that gamers can think about playing and game developers can think about building stuff. Motion is one that we’re very focused on.

Looking at what children are doing, particularly in education, but not only just for that—There’s a whole new wave of people growing up with a new way of learning and a new way of experiencing. A lot of it is game-driven. We’re interested in that, but also looking, as these children move into young adulthood, at how this next generation of people is going to be different from the current generation in terms of how they interact and learn, particularly in a gaming environment.

Guillaume Lautour: To me, there are three key things that are interesting right now. I see the return of difficult games. Game studios always talk about mid-core and hardcore and so on, but most of these games are actually super easy. Games were originally very difficult, if you remember the games you guys were playing 10 or 20 years ago. I’ve seen too many easy games in the last five years, these kinds of social games. I think difficulty is coming back.

Second, I’d like to see more connections in the industry between the Asian gaming market and the western one. We’ve seen transactions like Softbank acquiring Supercell, but that’s just one step. For now, those two markets are very separate. Both of them are huge, especially the Asian one. We don’t see many European and American players taking too much of an interest in the Asian market. That’s difficult to tackle, but I’m trying to do that a little bit.

The third thing is, I meet many studios who are experiencing deep problems between their founders, who want to stick to premium games, and others who want to do free-to-play games only. In France I see several examples of studios that have split this way, not being able to adjust to two different types of game design at the same studio. Most of the successes we see in mobile free-to-play games today are published by very small studios. It’s still difficult for the big publishers to tackle these kinds of game designs. I’d love to see a stronger appetite for success from the large publishers toward free-to-play games.

GamesBeat: The games business has created more value in the last few years than we’ve seen in a long time. King went from not being worth very much to $6 billion in value in the stock market. Zynga, $3 billion. Nexon, another few billion. Supercell, from zero to $3 billion.

We’re finding that it is a global business after all. In the top 10 acquisitions last year, nine of the buyers were from Asia. What are some of your own observations about how quickly all of this value has been created? How do you feel about it? Are you comfortable with it? Is it about time that this value has been created, or are worried about it in some way?

Buttler: I think it’s just the tip of the iceberg. I think it’s about time, but it’s also the right time. A lot has to do with the fact that the world is getting flat. If you create a hit today, particularly on the smartphone, it can be a global hit. It’s not longer contained to a certain geography or the small installed base of a high-end console. You are now making games that a billion people on the smartphone can play. They can all play it in a similar way. Monetization is solved, monetization mechanisms and platforms, all these things are in place on a global basis.

That makes the highs higher and the lows lower. You have thousands that fail and ones that become big hits. Some manage the combination of quality, luck, timing, and everything else to be in the top 20 or the top 10 and basically print money on a global basis.

In Asia you had this move toward mobile and online much earlier than here. Nobody had to deal with legacy businesses. As a result of these better business models in mobile and online, which have much higher margins, the Asian players have this tremendous domestic strength. They have 40 to 60 percent margin businesses. It’s huge money generation, and that now allows them to have this appetite and have the muscle to go global.

Even the top western players in the traditional console business, compared to the margins of a Tencent or a Nexon or any of the top Asian players, it just doesn’t compare. You have zero to 10 percent margins here and 40 to 60 percent margins over there for comparable leading players. If you have all this excess capital, of course you want to grow even more and replicate this in different territories.

Together with the global marketplace you now have and the platforms that are global, in my mind that will continue to fuel this trend. Once you break through and you have a hit or a quality title that you’ll be able to sell globally, you’ll be able to attract enormous amounts of money. $3 billion today is probably going to be $10 billion tomorrow, and so on. It will just continue in this way.

Baverstock: I’d very much agree with the first part of that. It’s the right time. It’s deserved. The money should be there. We’re seeing the fruits of a global business maturing.

I am slightly concerned about the western big market cap companies that have gone public recently. There’s a real danger that those are overvalued compared to their Asian compatriots, who have a much more solid business, much better diversified, and a very good stranglehold on their domestic market. There’s a risk that, at the top end, some of the western companies are not being correctly valued, and that will have a long-term negative impact on the investment climate for all of us trying to build businesses in this part of the world.

Overall, though, the global state of the industry is quite deserved. It’s a great place to be.

Jackson: I think the value creation we’re seeing right now is commensurate with the revolution in human communications, with the internet in its second or third iteration, however you want to count it. To your point, I’m concerned about the legacy publisher valuations, like Electronic Arts and others, which seem to be having a resurgence which is very short-term.

I also think that we’ve seen tremendous shifts in geography. Of course there’s Asia, but in my experience in the game industry, we’ve seen Germany come from being a consumer of games, not a creator of games, to being a key creator of games. There’s many examples. There’s Crytek on the engine and technology side, as well as the content side, but now you have this flourishing area in Berlin where you have all kinds of new mobile apps. To bring it home to France a bit here, one thing we can see is that France could have a tremendous resurgence itself.

Fear is a good thing. I’m definitely concerned and afraid of valuations. They’re crazy. They don’t make any sense. If you’re trained in finance at all, you can see that it’s very hard to predict where market valuations are going. I don’t think the motivations are there to really understand that. On a bigger, macroeconomic scale, we’re seeing the indication that the market continues to shift, both on a consumer level and on an enterprise level.

On that note, I’ll give a plug for one of the things that I think is a trend as well, and that’s what we generally call gamification – bringing game-like attributes to enterprise software and other types of software development or even old media efforts. Again, we’re at the tip of an iceberg there, where we could see the game industry transform into something we’ve never seen before, as it brings gaming formally into the workplace or the classroom.

Stokes: To throw a little bit of negativity in, just to mix it up a bit—I’ve done a lot of investments in the internet space. I’ve seen companies bought for a billion dollars that have zero revenues. When I see the sort of valuations you’re talking about here and I look at the revenues and the margins they’re generating, it can’t be that crazy relative to the craziness that you see in the world.

The thing that would be sitting in the back of my mind is, when I look at the internet companies, or to go back 20 years and even look at the Microsofts and the Apples, I don’t think there’s any brand affinity with King. I don’t think anyone has any brand affinity with King. The fact that these companies don’t have any brand affinity – it’s their products that have brand affinity – it’s a question of how far you can stretch that product affinity when there’s no real brand affinity.

I don’t think that’s what’s been pushed yet. That’s what we saw with Zynga. Zynga didn’t have any brand affinity with the public. It stretched its product affinity as far as it could, and then things collapsed. We’ll see what happens with King. That’s something that would concern me.

Baverstock: That’s very interesting. In the end, we’re a creative industry. Investors have to understand that you do need to make great product. You can’t just have a big business and turn out shit. People won’t buy it. It doesn’t work that way. There’s always a massive creative risk.

We’re in an industry where people often make comparisons with these other tech platforms, because we’re in the internet business, so it’s tech, right? It’s not. It’s a content business. That is a different perspective. It means valuations and profit margins have to be seen in a different light.

Stokes: Is it being valued as a content business? I don’t think it is, in the public markets.

Baverstock: No, and that’s one of my concerns about the current western valuations of companies like King and Zynga. I think they’re not being valued in the way that they should be.

GamesBeat: What do you mean by “valued as a content business”?

Baverstock: As I say when I’m talking about the old publishers—On the one hand it’s very hard to say that a company like EA, with properties like FIFA, isn’t a tremendously valuable company. But on the other hand, we can see today that they’re struggling badly to move their existing, very valuable, very well-known IP in to the markets that are growing. So it doesn’t matter who you are today. We’re in a very fast-changing environment and you have to recognize that that IP might not transfer to wherever we’re going to be tomorrow.

Buttler: I didn’t say it’s particularly easy to invest in gaming. I think it’s actually very hard. I also think it’s virtually impossible to predict which company will create the next worldwide megahit. It’s much easier to predict what will fail. It’s much easier to see when a team doesn’t jell or when an idea’s not great. To predict where a new Supercell will come from is virtually impossible. It makes early stage investing in games very difficult.

If you look at valuations across the board, they’re not high. The valuations are high for the ones that really break out. I think the only question is a question of timing. If you can invest in a Supercell when it’s just broken out and taking off, it’s a fantastic investment. When you come in after they’ve peaked – when they’ve gone through all this and you expect their next few games will be global megahits again, with these totally breakaway economics – of course you’re at the wrong side of history, basically.

That happened to Zynga, Supercell, it’s probably happening to King. But if you can come in after they’ve broken through and they’re in this upswing – League of Legends, many other examples – then you can have a fantastic investment. The trick is to find those that are just coming out of the soup, basically, where thousands fail, and haven’t peaked yet with that global megahit. If you invest at the absolute top, then you’ll have a problem, because the next game, or the next 10 games even, will have a very hard time following that.

GamesBeat: Guillaume, what’s your view of this sort of macro environment?

Lautour: The difficulty is in trying to value creative media businesses and compare them to what VCs and investors usually do, which is internet stuff or technology companies that build up recoverable businesses. The problem with media is that there is this production race. You can make a hit and nobody knows whether you’ll ever make another hit again. If King ends up being Candy Crush and nothing else, obviously $5 billion is too high a valuation.

Somebody said it’s super difficult to invest in gaming. I don’t think it is, in fact, if it’s something you specialize in as a media investment. People who succeed with their games are talented, but they’re also very hardworking. They have to equip themselves with the proper analytical platforms we talked about. They have to understand the platforms they work on. Many people talk about multiplatforming versus being specialized in one or another platform, switching from Facebook to Android or iOS without really changing the games themselves, even though behaviors on each platform are very different.

If you’re really hardworking and well-equipped and from the right generation, it should work. Maybe not for every title, but it should work for the long term. That’s what I believe. To come back to your question, I’m looking for entrepreneurs who stick to a platform, understand it from the bottom up. There’s a pace, a rhythm, a tone you need to make a successful Facebook game. There’s a speed and difficulty level. There’s a UI specificity to publish when you do something on iOS. It’s the same for console games, the same for PC games.

You can’t adapt every single thing. If you look at shooting games on tablets, every title still has some kind of control problem. How do you control a game with your fingers with such intensity? Some genres will adapt to some platforms, some will not. The platform has to be involved in that.

Coming back to a general macro view of the market, for me, gaming is looking fantastic as an opportunity. I was an investor in technology for 15 years. I’ve never seen such a thing. We have a revolution on three different fronts. If you look at Spotify and all these other platforms, they changed music on the distribution side, but they didn’t change the production. They didn’t change the business model for the entire industry. You can look at Netflix and everything that’s changing TV today. It’s not changing production. Netflix still has to invest $100 million or more to produce House of Cards. The only thing that has changed is distribution. When you’re only changing distribution, it needs to be a big game. You need to have a critical size before you’re successful.

In gaming it’s the opposite. We’re not only seeing a revolution in distribution thanks to platforms like iOS and Android and Facebook, but we also have a revolution in business models, thanks to free-to-play, and a revolution in production costs, which have been divided by 10. All of these combined, along with the fact that Facebook evangelized for games to hundreds of millions of people who never played games before, makes it a fantastic opportunity today. We’re just at the beginning.

When you think about it, a platform like Facebook or iOS will take 30 percent of your revenues. But if you sell at retail, they’d take more than 50 percent. The business model in gaming on mobile improves the gross margin by that 20 percent, right away. This is very profitable as an industry. I’m positive on the outlook. Yes, it’s difficult to price a single hit company, but I’m convinced that the quality of the teams and the professionalism that you can find within King will eventually allow them to publish additional successes.

GamesBeat: What’s a good micro strategy for entrepreneurs in this heady environment?

Jackson: One of the things I noticed at the conference here—I think we’re talking about two industries a lot of the time. There’s the traditional industry and then the digital industry, which is mobile, Facebook-oriented, driven by the analytics equation.

I just urge entrepreneurs to take on the lean startup culture. Try to seek out those methods. I truly believe the legacy industry doesn’t have a lot more going for it, unless you’re at a big studio. Most big studios are internal. It’s very hard to take entrepreneurial action in that area. If you’re specialized as an artist or a game designer, you can get hired into a large studio structure, but if you really want to participate in the newest wave, bringing in the startup culture, the culture of early stage company development — a very holistic approach to having all the pillars of good management and good business sense and good advisors – is important.

It was said many times these two days – are you making a product or making a company? I think you need to focus on making a company. This comes from 20 years in the industry, nearly 20 years.

Buttler: The real buzzword in Silicon Valley these days is not “big data” or anything like that. It’s actually “pivot.” Whenever things don’t work so well at a company in some way, it’s still cool, because they’ll pivot. It used to be, “Oh, I was wrong.” Now it’s, “Oh, we’ve decided to pivot.” That happens all the time. It’s a positive word now. I’m glad that’s the mindset, because it means, “We’re trying things. We don’t believe our own story, necessarily.”

If you look at Kabam, or even Zynga, and all these other guys, they did pivot and pivot and pivot. They didn’t even come from the gaming space. They let opportunity drive them, not their own story. That’s a tremendous strength an entrepreneur should have, to be able to pivot and find new opportunities, new things that people who have their knowledge from the old world won’t find, because they’re not listening carefully to opportunity.

Baverstock: On a related note in terms of understanding your business, a lot of games developers come at it from the point of view that they’re making a piece of art. They’re making something they care about. They’re passionate about it. They believe that if they make something great, people will share it and enjoy it with them.

There’s a fundamental fallacy there. People have to know about your product. I would encourage all small companies, all entrepreneurial teams in the industry, to engage with marketing as a function. Your marketing team and your game design team should be almost the same thing, and marketing should be as important to you, as a concept, as the game design you’re working on. There are very few developers who are that happy to engage with marketing in that way, but I think it’s very important that they do.

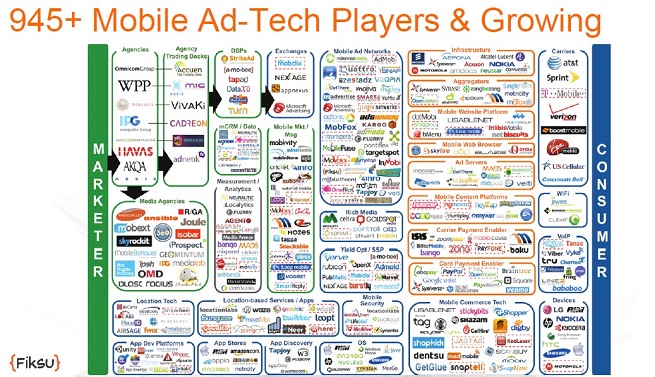

GamesBeat: Somebody had that slide elsewhere with all the ad tech companies. They showed that there are 945 mobile ad tech companies now. That seems a little nuts, but it also seems to address the twin problems of monetization and discovery that everyone is trying to solve. What do you think about the opportunities in that space? How should people sort through 945 companies?

Baverstock: I don’t think there are any easy ways of solving it right now. One of the most interesting things to watch in the industry is that discovery problem. If it starts to be solved, our industry will change dramatically again.

One of the core features of our industry right now is that nobody outside of the old-school console/retail space has a good discovery solution that works reliably, repeatably, and scalably. If we do come across that, that will tend to empower the big existing players with deep pockets against the currently disruptive small creative teams. The industry will change dramatically if a reliable, repeatable, scalable solution to discovery comes about. Today there isn’t one. It’s the Wild West. Try some stuff and see what happens.

Buttler: I completely agree. One of the reasons the mobile messenger companies get these tremendous valuations—If you look at Line, or WeChat in China, or even Facebook, which is now working on mobile as a marketing platform, it all has to do with app discovery being completely broken. The App Store and Google Play are similar to Yahoo in the old days of the internet, where the entire search engine portal was basically just listing links of the cool sites on the web. That was the initial discovery model, before Google and others came in, and now we have a completely different paradigm.

Once we have a better app discovery paradigm for the mobile web, we’ll have a mega-revolution. We’ll also take off this other 30 percent, which you never had to pay on the web. The fact that Google and Apple can control this entire environment today—HTML5 and other tools for the mobile web haven’t really taken off. It’s a pity. But nothing in the history of technology ever lasts forever. This situation where you have two gatekeepers for the entire market facing all the disruptive forces in the world has never sustained itself. Things will change. We’ll have a mobile internet eventually and that will catalyze a lot more creativity again.

GamesBeat: What do you recommend as far as the size of a mobile game studio these days? How many people should it have? How many people should be on a team? How much money should it initially raise?

Audience: This is a question to sort of answer Dean’s question about the size of mobile game studios, which is something I think about quite a lot. I think there’s a size that’s the right size for the current industry, which is something like 10 or 12 people. There’s a size that’s huge, which also works well. I worry that there’s not a good way for mid-size studios to exist right now, because 30 people tend not to make a game — Double Fine is probably an exception to the rule – that’s three or four times better, or monetizes three or four times better, than a game from a 10-person studio. The burn just tends to be much higher. I’d be curious to hear, along the lines of Dean’s question, if there’s any way to solve that problem in the long term.

Jackson: There’s the Supercell example, at a conceptual level, which is that you have to look at yourself as an incubator that’s working on multiple titles. If you’re a 30-person studio, you have to see that as five or six small teams that work quickly, that fail fast, and that you can move people around so you’re not losing a company culture, not losing investment in people. We haven’t exploited the incubator/accelerator model. It’s not necessarily about incubating small companies, in the same way that it’s done in other parts of tech. But I think there’s an application for creating games that hasn’t been found yet.

Baverstock: To pick up on that question of scale, 10 or 12 is great if you’re talking about a real startup, taking risks, trying something out. If you have an existing business with a reasonably successful game and you’re trying to make sure it’s a resilient longer-term business, you don’t want to keep those kinds of risks. Having 30 or 40 people in your studio might not make you a game that’s four times as valuable, but it will make you much more likely to deliver a good game. If you can afford that higher burn rate, you are trying to get yourself to a more reliable, longer-term situations.

It’s all about that difficult second album, right? It’s all about trying to go from something that worked – being as small as possible and doing as many games as possible – to locking it in and starting to build your audience and your community, and not continuing to take those same risks, if you can afford it.

Editor: The following is some introductory material about each investor:

GamesBeat: Please introduce yourselves.

Guillaume Lautour: I’m a partner at a VC firm based in Paris, IDinvest Partners. We’re investing around Europe, and we’ve recently invested in some companies based in the U.S., on the west coast. I’m a steady investor in two game studios. I’ve founded seven game studios up until now, all based in Europe. Some of them are still very tiny, seed-stage stuff. We do seed investments as well, as little as half a million, up to later-stage investments in companies we’ve seeded already.

We have companies like Social Point, for instance, 200 people based in Barcelona and France — they’re successful on Facebook – as well as four or five other different studios. Most of them were originally working on Facebook games and switched to mobile about a year ago.

Lars Buttler: I’ve been a serial entrepreneur and investor. I’ve started three companies in my life. I think I can relate to anyone who’s trying to raise money and build something. Before my last startup, I was at the Carlyle Group, which is the world’s largest private equity firm. Now I’m at Madison Sandhill, which is a VC in Silicon Valley, on Sandhill Road.

Right before this I actually started a gaming company and raised almost $500 million in a combination of equity and co-development and debt. That, for gaming, is not too easy. Then I started this VC company.

I’m very happy right now to look at many different things — big data, gambling even – but gaming is still a big passion. I’ve already made my first few investments in gaming. I’m very interested to see what’s going on in Europe as well, since I grew up in Europe. I have a special interest in what’s happening here.

Marc Jackson: In my current iteration I’m an angel investor and one-man incubator. I’ve set up six companies in the video game industry in the last five years, where I invest a small amount of money and provide advisory services. They’ve all been in games. One of them is Big Red Button Entertainment, which is doing the current Sonic Boom title. That took about four years to incubate, and is now a very large 70-person studio doing a console game in Los Angeles. I also helped incubate a company called Fearless Studios, set up in late 2010, which got sold to Kabam in 2012.

I advise investors, and I’ve been a specialty structured project finance risk manager and evangelist, bringing film and television style financing to games, which worked quite well in the mid-2000s. It may have a resurgence now with new business models, and I’m looking at doing some of that. I’ve also been involved in spearheading and setting up two gamification-type projects, one addressing e-learning and another addressing energy efficiency.

I have a diverse set of interests, and I’ve worked very closely with founding teams at a very early stage to set up primarily game-focused companies. I’m also a French citizen. I earned my MBA at HEC in Paris, and I have a great love for France. I hope to be doing a lot more business here.

Ian Baverstock: I’m at Tenshi Ventures in the U.K. My background is very much as a games developer. I started as a developer in 1989, with my colleague Jonathan Newth. We built that company up into a 300-man U.K.-listed company, sold it a couple of times, and did very well.

We’re now very much interested in helping other small companies get off the ground. We’re seed investors. We’re looking at the angel space, rather than large amounts of money. We like to get involved with the companies we work with and add advice as well as cash, in fact particularly the advice. You need their passion and energy, but sometimes you need the wise old gray-haired person in the corner saying, “No, don’t do that. Do something else instead.”

I also do some work with the U.K. government on the innovation side and in creative industry strategy. But here I work with my games background. That’s all.

John Stokes: Prior to being a venture capitalist I was a moderately successful entrepreneur in Asia Pacific for about 12 years. I had experience in mobile, in startups starting mobile, and then starting in internet and finally in media. Our fund is based out of Montreal, primarily investing in Canada, but doing a few North American investments, and we’re not averse to looking at European opportunities.

We are really a web/mobile investment firm, but we have been dipping our toe in the gaming industry, and because of our base in Montreal, we’re doing more. So far we’ve invested in one studio out of Toronto called Massive Damage. We’ve invested in an accelerator/incubator out of Montreal, Execution Labs. We’ve also invested in a couple of peripheral gaming companies. One is a player acquisition company out of Vancouver, and we’ve also invested in a hardware Oculus Rift competitor as well.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More