Andrew “Bunnie” Huang lists a bunch of reasons why you’ll want his open-source laptop, the Novena. You can modify it yourself so that its battery will last however long you want it to. You can inspect the software to see if there’s any present from the National Security Agency. And you don’t have to pay a tax to any big corporation just because you want to do some computing.

It’s all part of the do-it-yourself hardware movement that is giving us things like 3D printing, cool robots, and virtual reality headsets. Huang recently unveiled his ARM-based quad-core Novena laptop, which has air-pump hinges so you can easily get under the hood and modify it. He is raising $250,000 on Crowd Supply so that he can build and ship initial units to crowdfunding contributors. The machine costs about $1,995 now, but that price could come down over time if volume sales are good.

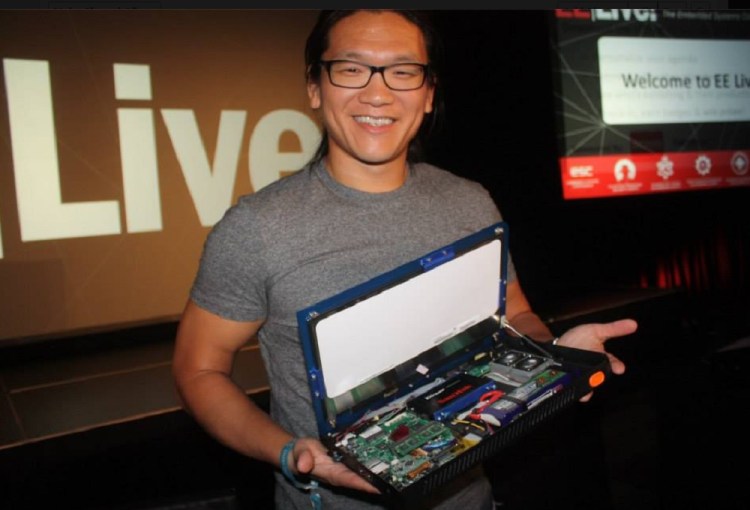

Huang, a Singapore resident who gained fame for hacking the original Microsoft Xbox game console, introduced the machine as a “labor of love” at the recent Embedded Systems Conference in San Jose, Calif. He hopes that a community of hardware hackers will rally around the machine and contribute all sorts of modifications. We interviewed him at the ESC. Here’s our edited transcript of our talk.

VentureBeat: Did some of the ideas for this go back as far as Chumby (the maker of embedded Internet computers that shut down in 2011)?

Huang: Chumby was open source and hardware. We had been doing a lot of embedded systems using Linux. Definitely, there’s a thread with it. But part of the motivation behind this is also lessons we learned from Chumby and things we wanted to do differently.

VB: Is there anything else out there doing something similar with an open-source laptop?

Huang: There was a move by one company – I think Asus or someone – to build an open case. They released all the plans and so forth. They didn’t manage the community quite right. There’s a lot of community involvement and outreach you have to do. You can’t just put the plans out there and expect it to happen. It’s a lot of work.

VB: Your choice of processor, did that involve the fact that it didn’t have a non-disclosure agreement involved?

Huang: Yes, absolutely. That was very important.

VB: I imagine that must have been a problem with a lot of other processors.

Huang: Yes – actually, almost every other processor choice out there wasn’t feasible. Don’t get me wrong. The Freescale processor is really good. It does a lot of things exactly right for our target market. But there’s also some pretty tasty silicon out there that’s just totally locked up with non-disclosure agreements. I couldn’t even get a meeting to discuss it. My volume expectation wouldn’t be big enough.

VB: What’s the significance of this for you? Why do we need open source hardware?

Huang: There’s a number of threads to pull on there. Just from an ideological standpoint, the idea that we can share and learn more about the things that we’re using is enabling in a lot of areas – education, research. People who are doing industrial designs, also, controllers and so forth, need to have access to documentation. There’s a number of areas where this is important.

There are more practical, immediate concerns, like the whole issue of security and tampering with machines that’s come up recently. We know that’s happening these days.

VB: You’re trying to make something NSA-proof?

Huang: Not NSA-proof, but you have some recourse.

VB: It would be much easier to spot any snooping.

Huang: Yeah. You can find the bug. In other designs, it’s hard to find the bug. In this one, it’s easy. So there’s a number of reasons. But for me it’s primarily ideological, to be able to get something out there that’s open and fully enabling.

The thesis is that as you build a community on it, you get this long tail of innovation. Things we never expected to happen start coming out, things we couldn’t do. That adds back into the pool and we all start playing with each other’s work and riffing off each other. You get a rich ecosystem.

VB: The prices are a little higher than the commercial equivalent. Can you explain why it’s more costly?

Huang: It is a little more expensive than your low-end feature laptop. It’s comparable to the Macbook Pro kind of lines. Of course, the heirloom one is astronomical. But these are not totally out of line. They’re just not on the discount rack.

Part of it is we’re targeting a more niche market. We don’t have a volume expectation at the level that you would need to amortize a run selling at a few hundred dollars apiece. In running the campaign, we want to make absolutely sure we can deliver a product if we fund at a reasonable expectation. We’re only, or “only,” looking to raise a quarter million dollars, which is big for a crowdfunding project, but in the context of a laptop, it’s actually quite small. The price is a little higher because we’re trying to amortize a lot of the up-front costs of doing the tooling and machining and so forth across a relatively small number of units.

VB: So if you start getting volumes in the thousands or something…

Huang: If we got to those kinds of volumes — that’s well beyond the expectation of the campaign. We didn’t want to set a minimum bar of like $2 million or $5 million before we started. We wanted to be able to serve a small community of enthusiasts. If it goes bigger than that, great. But we’re realistic.

VB: This case here, it seems like something you just wouldn’t do or couldn’t do on a commercial laptop.

Huang: No, it’s wacky. The air piston isn’t cheap. We do use a blend of fairly premium parts in this design. The machined aluminum is unusual, because machining is expensive when it comes to mass production. Usually it’s stamped or injection-molded. We made a few decisions that increased the per-unit costs a bit but drastically decreased the amount of money we had to raise.

VB: Could you explain the version of Linux you’re using?

Huang: We’re using Debian. Debian in particular, they have an ARM HF build for all of their packages, so you can apt-get install basically anything. You don’t have to build it yourself. It was down to choosing between Debian and Ubuntu. Ubuntu is more about a solid user experience on an x86 system. The ARM support was a bit lacking. Debian is a more free and open distribution. They expect you to be able to customize. So Debian ended up being a better match for what we were doing. We had more flexibility to pick different window managers and other configurations.

VB: What was it like finding this processor? Was it easy to make that decision? Did it already have some open-source history?

Huang: I have a long history with Freescale. We had designed with Freescale CPUs at Chumby, and so we’re using the same network of contacts in sales from back then. They were always on the list of guys we were considering. We did a comprehensive survey across Samsung, Nvidia, Marvell, Freescale, Broadcom, and a couple of other guys. After looking along all the axes and all the things we considered, Freescale was the right choice for us. We had this kind of table of greens and reds. They had a lot of green in their column.

VB: Besides just the NDA thing, did they have a certain philosophy that matched with yours?

Huang: Their design point these days is more toward people who have — not necessarily pure consumer apps, but they’re strong in automotive, they’re strong in industrial controllers. They have an automotive temperature grade. If you need to do a ruggedized version, they have that. Their product cycles are long. If we need to support people for five or 10 years on this platform, we know we can buy the silicon from Freescale for a long time. That’s fairly important when you’re looking to do community growth over years and years.

VB: I wanted to ask, have you looked at the Xbox One’s security at all?

Huang: No, I haven’t. I’ve been too wrapped up with this.

VB: Are you retired from the Xbox hacking business?

Huang: Yeah… I mean, so many really good hackers are looking at this stuff now. I feel like my work is done. We have a community that looks at this stuff now. They’re strong at doing this sort of thing. There’s no need for me to keep on telling people, “Hey, this is hackable!” They’ve got it.

VB: Why does the laptop include a field-programmable gate array?

Huang: The FPGA was initially just something we included on a whim, but it turns out to be a really good idea. For people who want to extend and customize their own thing, the FPGA is an enormously useful feature. Particularly in this crowd, which is very technical, when I said there was an FPGA, people were nodding their heads out in the audience. With the FPGA, you can do a whole host of things as far as control systems and design that you can’t do without it.

VB: Intel and some other big companies are paying attention to the DIY hardware market now.

Huang: Yeah, they’re starting to take an interest. Galileo is coming and so forth.

VB: I don’t know what you’d think of Intel’s intentions these days, but are they moving in a direction that’s helpful?

Huang: I think so. I do like that there’s an ecosystem forming and that bigger players are starting to validate the model. It’s maybe not as open as I would like, but I think any move in the right direction is good. I’m pretty agnostic about that. As long as people hop on board, that’s great.

The traditional model, where you rely on the Asuses and the Acers to come up with your innovation is retiring a bit. They’re looking now for smaller teams of people with good ideas who don’t necessarily have the resources of big corporations, people who can keep cranking out smaller, faster, better on that Moore’s Law curve. The acknowledgment of the DIY community says, “Maybe there’s some low-hanging fruit we can go after now that we’re not constantly just keeping up with Moore’s Law.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More