The fashion industry has its own Sherlock Holmes, and thanks to him, one of the Internet’s largest traffickers in counterfeit goods is going to pay.

And that Sherlock is a PI from Plano, Texas. Named Holmes.

Rob Holmes is a private investigator and owner of IPCybercrime in Plano, and he blew the lid on one of the world’s biggest counterfeit goods sales sites with a year-long undercover operation. In doing so, he may have helped give brands a new legal tool in their attempt to stamp out billions of dollars in sales lost to counterfeiting each year.

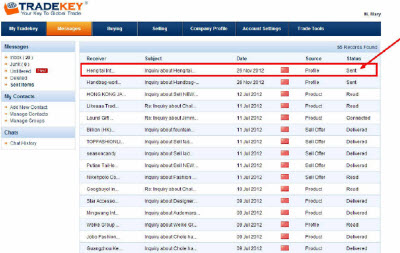

In an interview with VentureBeat, Holmes said his work helped unearth evidence that the Pakistani e-commerce vendor TradeKey helped enable wholesale trading of thousands of counterfeit goods over the Internet by setting up a “virtual swap meet” where vendors could sell fake goods with impunity. A federal judge ruled on Oct. 8 that TradeKey had violated copyright law and contributed to the counterfeiting of goods made by companies, including Holmes’ client, Richemont, the owner of six luxury fashion brands including Mont Blanc-Simplo, Cartier, Chloe, Alfred Dunhill, Officine Panerai, and Lange Uhren. Holmes said he found thousands of cases of large-scale counterfeit listings during his undercover work.

Above: TradeKey counterfeit listings.

Holmes told us how, at the request of Richemont’s lawyers, he organized the undercover investigation with luxury brand company’s legal team as it pursued TradeKey, a site that had more than 5 million members at the time of the investigation. The tale is a case study in how big brands are going after shadowy counterfeiters and how tricky it can be to collect evidence that will bring those counterfeiters down.

The case could set a new legal precedent, since an earlier ruling in 2010 put the burden of stamping out counterfeiting on e-commerce sites on the brand claiming to be a victim. In the case of Tiffany v. eBay, the U.S. courts ruled that eBay was not responsible for policing its market for counterfeits sold by third parties. That decision put the burden on brands to provide proof to eBay if they wanted it to take down a counterfeit sale.

But in the TradeKey case, the evidence of counterfeiting was so widespread throughout the site that a federal judge ruled that TradeKey was in fact responsible for curbing counterfeit sales. That ruling by U.S. District Court judge Gary Allen Feess in Los Angeles is the latest result of a one-year investigation and three-year legal case against TradeKey. The judge found that TradeKey had “actively promoted and facilitated the sale” of counterfeits. He ordered it to monitor its sales.

“This is the first case that holds an online marketplace liable for contributing to counterfeiting,” Holmes said in an interview with VentureBeat. “And they were the No. 1 counterfeiting site in the world. This was the big, bad one.”

It’s hard to verify if TradeKey was the biggest counterfeiting site, but Holmes does work for about 50 brands, and the lawyer for Richemont agrees it was a big one.

“We believe the case is groundbreaking in the magnitude of the counterfeiting on TradeKey.com,” said Susan Kayser, legal counsel for Richemont at the law firm Jones Day, in an interview. “Rob Holmes’ investigation was essential to the case. The court relied heavily on the investigation’s findings in its ruling.”

TradeKey’s attorney, Erik Syverson of Miller Barondess, said in an e-mail, “We completely disagree with the court’s ruling, factual findings and application of the law, particularly with respect to contributory liability principles. Followed to its logical conclusion, this ruling requires web sites that permit user-generated advertising to proactively screen for infringing or counterfeit items listed for sale. That is not the law.”

He added, “The law has always required that trademark owners perform such a function. Furthermore, the ruling impermissibly restricts the legal use of trademarks in meta data and adwords, even by third parties not connected to this lawsuit. For example, under this ruling, I cannot list for sale on my client’s website my own collection of authentic Mont Blanc pens, or even mention Mont Blanc for comparative advertising purposes.”

He said TradeKey is considering its options. He did not elaborate.

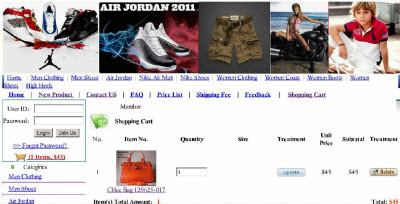

Richemont identified TradeKey as a significant purveyor of counterfeit goods in 2010, according to Holmes and Kayser. Posing as Ray West (an evil alter ego that Holmes used as a fake identity), Holmes opened a free account and began making purchases on the web site. He was able to make high-dollar purchases of lots of counterfeit goods. The shipments confirmed to Holmes that counterfeit goods, such as the Chloe purse pictured at the top, were freely being sold on the TradeKey web site. He sold and bought counterfeit watches and jeans, Holmes said.

Once he built up his reputation on the site, Holmes, still posing undercover as West, asked if he could become a Gold Key member, Holmes said. He paid $3,000 and received access to his own personal TradeKey representative. The representative gave him tips on how to market products on the site. The rep also taught him how to sell counterfeit goods, known as “replicas,” Holmes said. The representative said that TradeKey relied on counterfeit sales as a large part of its revenues, Holmes said. As a Gold Key member, Holmes could take out special paid ads promoting his goods.

According to the court documents, Holmes found more than 6,000 sellers offering branded products on TradeKey.com, including more than 2,400 sellers with listings for Chloe-branded goods, 200 sellers of Dunhill-branded goods, 850 selles of Panerai-branded goods, 500 sellers of Mont Blanc-branded goods, and 1,900 sellers of Cartier branded goods. None of those sellers was authorized, Richemont asserted. Holmes himself bought eight Chloe handbags, which were listed at rock-bottom prices. He also bought an Alfred Dunhill belt, a Dunhill dress watch, five Panerai watches, two Mont Blanc watches, and four Cartier watches. Pictures of the goods proved they were fakes.

TradeKey did not make money from a cut of transactions, but it did make money through the ads and memberships, the court filings said. Using TradeKey, Holmes could contact customers about doing transactions with fake goods. He placed an ad on the TradeKey.com homepage. He used the word “replica” in that ad, but for the homepage, TradeKey.com took the precaution of removing the word from the listing. However, Kayser noted that TradeKey.com still permitted the ad to run on its homepage.

“We made a whole bunch of purchases first showing how easy it was,” Holmes said. “We extracted tens of thousands of listings with counterfeit marks. We made purchases from the biggest sellers. They would sell 1,000 or 10,000 at a time.”

Above: TradeKey counterfeit listings.

The TradeKey representatives didn’t ask Holmes to meet them in person. TradeKey’s sales department had “replica products” and “replica retention” divisions, according to the court’s order.

Kayser said, “TradeKey was operating a virtual swap meet for counterfeits.”

The investigation lasted for a year. Prior to the investigation, Holmes made a name for himself as one of the investigators who tracked down pirates of Call of Duty games.

IPCybercrime went to TradeKey’s U.S. Internet service provider, Liquid Web in Michigan, with an order to seize servers. The investigators seized data from 42 servers and more than 100 hard drives. The court found that TradeKey.com operated mirror sites, saudicommerce.com and b2bfreezone.com.

Holmes said that TradeKey had found a way to steer internet searches toward its handbags and other replica goods via inserting the word “replica” into the meta field for a search. While most of the undercover work was plain gumshoe tactics, Holmes said he has to incorporate technology into all of his investigations. The fact that TradeKey used an ISP in the U.S. made the investigation easier. But that also gave TradeKey much better search engine optimization on Google.

At one point, Holmes said he was worried about whether he was being followed. His team is relatively small, and he investigates counterfeiting and piracy for brands in fashion and gaming.

Holmes said Richemont’s legal team played a big role.

“They had a strategy and it was brilliant,” he said. “They took it nice and slow, not missing anything.”

The downside for Holmes? He has had to retire his alter ego, Ray West, from duty. He grew emotionally attached to that false identity over the years.

“He was my evil twin,” he joked.