“If advertisers can convince people to smoke and eat Micky D’s, they can convince them to disable Do Not Track.”

So says Christopher Soghoian, a security and privacy researcher at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) who argues that one of the biggest problems advertisers face with Do Not Track is convincing web surfers that they don’t need to use it.

For advertisers, behavioral tracking is an effective way to develop a strong profile on web users so they can better target ads. But for privacy groups and web users, it’s a massive breach in privacy that goes against the most basic tenets of the web. Originally proposed in 2009, Do Not Track is the “Do not call” of the digital age, a way for users to tell advertising companies that they want to opt out of behavioral tracking. (Even Microsoft’s jumped onboard of the Do Not Track effort.)

But in order to prevent an increasing number of people from opting out of behavioral tracking, advertisers have had to use an effective, if controversial, trump card: Opt out of behavioral tracking, they warn, and you could destroy the free Internet that you’ve grown to love so much.

The thinking goes like this: If advertisers suffer, so, too, do online publications and websites that rely on advertising for revenue. The idea is to show that the relationship between advertising and the Internet is symbiotic, not parasitic, and that Do Not Track would have an effect more like a guillotine than a privacy curtain.

It’s an argument that the advertising industry has been making for over 10 years, as Abine privacy analyst Sarah Downey points out. Downey cites Michael Tchong, the editor of now-defunct ad industry newsletter Iconoclast: “All this free content isn’t going to continue to be free unless users pay for it somehow, and the payment is advertising,” Tchong said in 20o0. But here’s the thing: Tchong was talking about pop-up advertisements, not behavioral tracking.

“Advertisers need to be more creative with their arguments,” Downey said in an interview with VentureBeat. “It’s a weak connection and they keep making it.”

The extent of this weak connection is evident in the ad industry’s own revenue numbers. According to figures from the Interactive Advertising Bureau, online advertisers made $31.7 billion in 2011. Of that, $4.9 billion — just 15 percent — came from behavioral advertising. This, Downey says, makes it hard to argue that behavioral tracking is something that advertisers desperately need.

ACLU legislative counsel Chris Calabrese agrees. “This idea that we suddenly need to track everyone, and that that’s an integral part of providing content, doesn’t pass the sniff test for me,” he said. “I have a hard time seeing how taking this one small slice away is going to harm the ad people very much.”

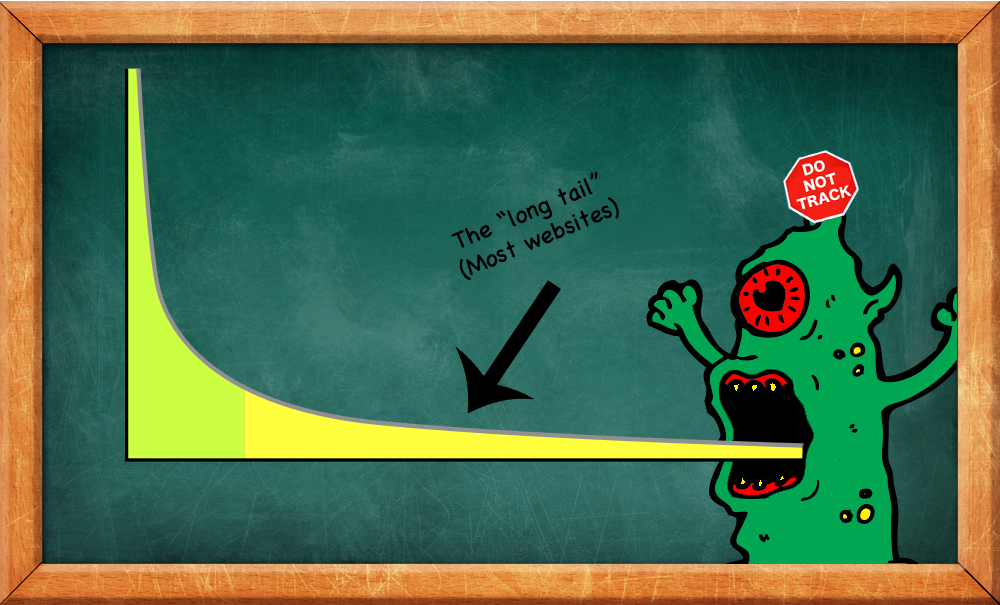

But if you ask the ad industry where the damage will be, it doesn’t point to its own bottom line. The real danger, it says, will be to the majority of ad-fueled websites online — the so-called “long tail.”

“Behavior-based advertising is absolutely critical to the long tail,” says Marc Groman, the director of the Networking Advertising Initiative. “And if that goes away, I don’t know how most websites are going to monetize their content.”

To understand the concerns, it’s worth thinking of two Internets rather than just one. One Internet consists of established sites like the New York Times and CNN, which rely more on the sort of banner-based advertisements you see around the web. Unlike behavior-based ads, these appear based on what advertisers know about a website’s readership. How old are they? What are their interests? Where do they live? It’s the classic advertising model.

But that system breaks down when you start looking at less significant sites with smaller, more fragmented audiences. How can sites like these sell ad space when they know almost nothing about the people who are visiting?

“Behavioral advertising is useful when the contextual ads are not worth very much,” says Soghoian. “Banner ads aren’t going to help your stamp-collecting blog.”

So is there a chance that the advertisers are — gulp — right about this on some level? It certainly looks that way.

“What Do Not Track may do is separate the strong from the weak on the web,” Soghoian says. “Sites with low value content could struggle while larger sites keep on going.”

This is largely the same reason why sites like the New York Times and Wall Street Journal can still thrive behind a paywall: They offer high-value content that readers are willing to pay for. A similar effort wouldn’t work for less-established sites.

But all of this is, again, hypothetical. No one on either side of the issue knows which way things could go, which is a part of the reason why those in the advertising industry want to err on the side of caution and stop Do Not Tracks in its, well, tracks.

“Nobody has any idea if this is going to impact the free Internet,” said Alan Chapell, an attorney and member of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). “It’s telling that we are three years into this discussion yet we still don’t have any idea how things are going to look,” he said.

But for people like ACLU’s Calabrese, one thing is certain: The harms of behavioral tracking far outstrip the potential benefits of getting free content.

“The tracking comes with a lot of harms to the basic ways that people use the web,” Calabrese said. “If you are worried about tracking you may think twice about going to sites like Wikileaks. These fears have very real effects on how people use the Internet.”

So we end up right where we started. While behavioral advertising may be vital to the current makeup of the web, the question worth answering now is this: Is that really the kind of Internet that we want to use in the first place?

Photo, chalkboard/ Shutterstock

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More