King disclosed its financial results today as part of a filing to raise $500 million in an initial public offering. The disclosure gives a real picture of the financial state of the European company behind the smash mobile gaming hit Candy Crush Saga.

King said that it had profits of $568 million on revenues of $1.884 billion for 2013, compared to profits of only $7.8 million on revenues of $164.4 million in 2012. The success of one game and the huge growth of casual gaming on smartphones and tablets are largely responsible for this huge difference. The ability to play games anytime and anywhere is causing rapid expansion of the gaming audience.

“At King, our core mission is to make everyday life more fun,” wrote Riccardo Zacconi, chief executive of King, in a letter to potential shareholders in the filing. “This is what gets us up in the morning and, ultimately, what has driven us towards this point in the company’s development. We have strong titles, a proven game development and business model, and a keen focus on building a substantial business over the long term.”

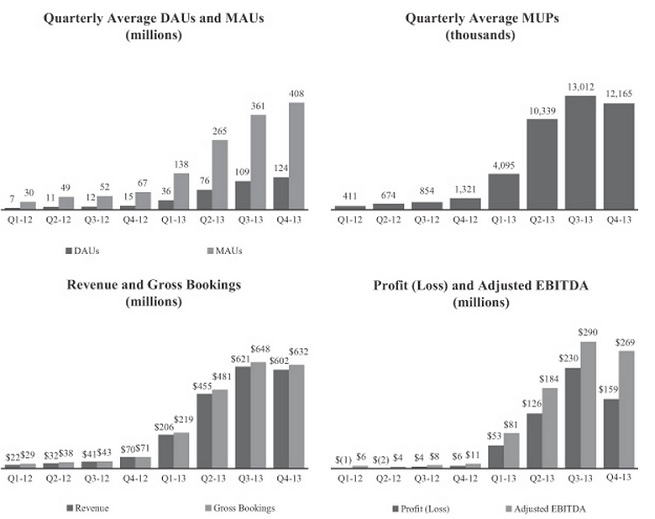

Some observers have said that King is a one-hit wonder, with 78 percent of its revenues dependent on one free-to-play mobile title. As you can see from the chart at the bottom of the page, many of King’s key metrics hit a plateau in the fourth quarter of 2013. Its strategy is to outrun the laws of gravity by riding the mobile wave and producing a continuous and broad pipeline of diversified casual gaming hits.

Adam Krejcik, an analyst at Eilers Research, called King’s growth in 2013 “staggering” and comparable only to rivals Supercell, maker of Clash of Clans, and GungHo Online Entertainment, maker of Puzzle & Dragons.

“Candy Crush Saga has set the bar in terms of what a successful free-to-play game can now generate in revenues and profitability,” Krejcik said.

Zacconi has been trying for a long time to adapt King’s casual gaming business from the web to Facebook and mobile. Because he has succeeded so far in that transition, he is enjoying a huge financial windfall. Zynga, the company’s chief rival in social games, stumbled in the transition to mobile and has had a hard slog for almost two years now. King’s financials may be built on a single game, but many game companies would kill to have its business and its chance to go public right now.

If it continues to prosper, King could go public and give investors a desperately needed option among digital gaming plays. We’ve looked through the filing and have learned some interesting things that will be useful to investors trying to determine whether King is a good investment or not.

Eric Goldberg, managing director at Crossover Technologies and a longtime game-industry consultant, said that a lot of the calculations come down to speculation over how valuable Candy Crush Saga is, its ability to point users to new King games, and how long it will last. Of course, if these risks scare you, or if they scared King, the gaming industry would be pointless. Games are hit-driven entertainment. Risk is part of the game.

King is based in London, and it has its major studios in Stockholm, Sweden. For filing purposes, however, the company has classified itself as an Irish company, based in Dublin. During its rise, King has seen many industry-changing events such as the shift to social gaming, the rise of mobile, games as a service, the growth of the casual audience, and the free-to-play business model.

The company has been patient and methodical since its founding as Midasplayer in 2002. It first became profitable in 2005 on casual games that often involve puzzles and are easy to learn but hard to master. King published hundreds of casual games on its King.com website and attracted about 10 million users. Once Zynga started making a splash on Facebook in 2008 and got hundreds of millions of users, King turned its focus to social games to join in on the action. Zacconi watched Zynga’s growth closely and wanted to capture some of the magic it had in getting large numbers of users so quickly.

King’s earlier games were modest when it came to social features. The company was publishing about 15 games a year on its website, but it was slow to shift to Facebook at first. When it launched Bubble Witch Saga and later Candy Crush Saga on the social network, the games shot to the top and gave Zynga some serious competition for the first time. King captured a shift that was happening on Facebook and on mobile as players shifted from simulation games like FarmVille toward faster, arcade-like games with shorter playing cycles. Those games were easier to play while waiting in line at the coffee house, and Zacconi says his company is focused on creating “bitesize brilliance.”

Zacconi’s teams, led by seasoned leaders like Tommy Palm in Stockholm, created and debugged Facebook games one at a time. Then, once they were ready, they launched them on mobile platforms such as iOS. They did it that way because it wasn’t as easy to quickly debug and update games on mobile. Once the teams had the virality and monetization figured out, they launched the titles on mobile. So King had a big funnel of a few hundred web games, a smaller number of Facebook games, and a handful of mobile titles.

King kept its teams small. Palm led a team of three that worked on a mobile version of Candy Crush Saga, which took advantage of the rapid adoption of smartphones and tablets by the hundreds of millions. The Candy Crush designers created hundreds of levels, so players would never run out of something to play. They continuously updated the game. Other titles in the Saga series are similar, with hundreds of levels and plenty of social hooks to keep gamers playing with their friends. King’s games are cross-platform, allowing players to stop on one device and pick up the game on another.

In its filing, King said this process was “repeatable and scalable,” and that King has 180 game properties that it owns. It’s not clear how many of those game properties will lead to repeat hits on mobile.

For investors, that’s the crux of the question. Will it keep on producing the hits? By comparison, King has more mobile revenues than Electronic Arts, which has more than 900 mobile games. EA has hits such as The Simpsons: Tapped Out, but it just hasn’t come up with a game with staying power to occupy the No. 1 or No. 2 position for a year like Candy Crush Saga has.

King describes its game as an “entertainment franchise,” but John Riccitiello, former chief executive of EA, questioned last fall at our GamesBeat 2013 game conference about whether such new titles could really be considered franchises alongside EA’s Madden Football or Nintendo’s Mario. He asked whether such “franchises” would be around in five years. By comparison, on the consoles, games like Call of Duty dominate the charts year after year.

The King that matters to investors has been in existence for a short time. The company offered its first virtual currency to players on Facebook in September 2012. That turned into its primary source of revenue. In October 2012, King launched Candy Crush Saga. The title became one of the most downloaded apps in the world in 2013, and it remains in the top ranks.

King reported that Candy Crush Saga has 93 million daily active users who play the game 1.085 billion times a day. Its next most popular game is Pet Rescue Saga, with 15 million daily active users and 129 million daily game plays. Farm Heroes Saga, Papa Pear Saga, and Bubble Witch Saga are also popular, but not nearly as popular as the other two. The point that King naturally wants to make is that it has multiple top-ranked hits, not just one. It also notes that Bubble Witch Saga is a long-term hit and that 73 percent of its revenues in the fourth quarter came from mobile platforms.

King also gets more installs of its new games because it can advertise them inexpensively via its network of 324 million monthly unique users. The enormous revenues from Candy Crush Saga also allow King to spend more money than its rivals on paid advertising, so it can replenish the Candy Crush Saga users who leave the game with fresh players. Social game companies who engage in such tactics have to be careful about their advertising spending, since it’s easy to spend too much money on users who won’t become loyal players or spenders. King says it runs thousands of discrete, targeted ad campaigns that are aimed at individual users it believes will be likely Candy Crush Saga players. King also targets existing players, prompting them to make purchases of virtual goods with real money — the primary source of revenue in its games where users can start playing for free.

Krejcik of Eilers Research noted that King’s percentage of players who pay for virtual goods is 4 percent of the total base, which is higher than a number of other companies in the space. Zynga’s conversion rate is around 2 percent.

Zynga also thought it had huge franchises that would never end, but its dreams of a gaming empire fell apart in the past couple of years as its brands proved that they had limited staying power. But King can argue that it is different in some respects. King spent only $110 million on research and development last year, compared to $28.6 million the year before. That’s a small amount, compared to other game companies. King’s sales and marketing costs, on the other hand, were pretty high at $376.8 million in 2013, up from $55 million the year before.

Revenue per employee is a good measure of a company’s efficiency in generating revenues. King had 665 employees as of Dec. 31. With $1.884 billion in revenues in 2013, King had $2.83 million in revenue per employee. When Zynga went public, it had roughly 3,000 employees and $1 billion in revenue, or about $333,000 in revenue per employee. So King appears to be much more efficient in that respect, and it has been cautious about hiring too many people. Zynga, by comparison, has had to cut back by about a third on its headcount as its revenue stalled. GungHo Entertainment, with about 700 employees and $1.6 billion in revenue, has about $2.2 million in revenue per employee.

Another example is Supercell, which has about 190 employees and 2013 revenues of $892 million. That adds up to $4.69 million in revenue per employee. It doesn’t get much better than that. That is no doubt why SoftBank paid $1.5 billion to buy 50 percent of Supercell at a $3 billion valuation. King is so much bigger, though, it’s unclear who would really have the money and the will to buy King in the game business. So its best option is an IPO.

King has grown its staff dramatically, opening five studios in Europe since October 2011. But even at its size, King has huge rivals in gaming, including Activision Blizzard and Zynga itself, which is banking on a comeback under the leadership of new CEO Don Mattrick. In fact, Zynga’s acquisition of NaturalMotion for $527 million may have prompted King to make a strategic move of its own.

King was named the best company to work for in Sweden, but it may not have an easy time expanding a lot further, given its unpopularity among game developers at the moment. King started enforcing its copyright on terms like “Candy” and “Saga,” so much so that it even sued makers of unrelated games like The Banner Saga. A developer advocacy group, the International Game Developers Association, said today that King was “overreaching” by trying to enforce its copyrights so broadly. The copyright issue has earned King the wrath of the industry and has made it more unpopular as a company than any other time in its history.

Fortunately for King, it isn’t under huge pressure to go public, even though it has filed. Analysts expect King to raise $500 million in the IPO at a valuation that could hit $7 billion, but it doesn’t need a lot of cash to run operations. Krejcik estimated King would be valued at $5.4 billion to $6.7 billion.

As of Dec. 31, the company had $409 million in cash, up from $24.6 million a year earlier. During its existence, King only raised $9 million from Apax Partners and Index Ventures, while Zynga’s many investors were itching to cash out.

In the filing, King says its goal is to broaden and strengthen its unique model for developing hit games. It reportedly delayed its IPO earlier out of concerns that it was too dependent on Candy Crush Saga. Quarterly revenues and profits dipped in the fourth quarter, signaling some weakness in Candy Crush, but the company continued to add to its overall user base. Candy Crush Saga is so big that it won’t be easy to sustain the growth with a pipeline of new users, but that’s where King intends its other games to fill the gap.

If King can keep this machine going for at least a few quarters and continue the success post-IPO, then it will avoid the fate of Zynga, which is trading at about a third of its IPO price.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More