Nokia has been searching for new businesses to break into ever since it retreated from the smartphone business. And after a few years of research, the Finnish company decided to move into virtual reality 360-degree capture cameras.

The company launched its groundbreaking Ozo in March for $60,000, and then it cut the price to $45,000 in August. It is now shipping the devices in a number of markets, and it is rolling out software and services to stoke the fledgling market for VR cameras.

We talked with Guido Voltolina, head of presence capture Ozo at Nokia Technologies, at the company’s research facility in Silicon Valley in Sunnyvale, California. Voltolina talked about the advantage the Ozo has in capturing and processing a lot of data at once, and he talked about the company’s plans for expansion in VR.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

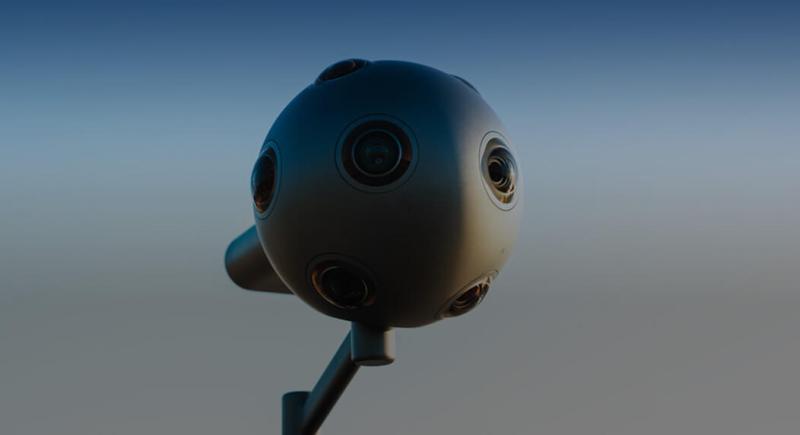

Above: Ozo in action

VentureBeat: Tell me why you moved into making the Ozo VR cameras.

Guido Voltolina: The whole project and division is called Presence Capture. The idea is that, as soon as we identified VR was coming — this was before the Oculus acquisition by Facebook — it was clear that one part of VR would be computer-generated experiences, games being the major example. But as we looked at it, we said, “Wait a minute. If this is a new medium, there will be more than just computer-generated experiences. People will want to capture something — themselves, their life, things happening in the world.”

We had to look at what would be the device that could capture as much data as possible in order to reproduce the sense of presence that VR allows you to have when you’re fully immersed. As a subset of VR, you also have 2D 360 images. That’s still happening. But that’s almost a side effect of solving the major problem we have to solve, these full three-dimensional audiovisual experiences that reproduce the sense of “being there.”

The team started thinking about a device purpose-built for that task. Instead of duct-taping different existing cameras into a rig — many people have done that — we designed a device specifically for the job. The Ozo is not a good 2D camera, but it’s an excellent VR camera. The shape ended up being the same as a skull, very similar dimensions, with the same interocular distance as a human being. It has eight cameras, and the distance is very close, with a huge overlap in the lens field of course. We’re capturing two layers of pixels to feed the right and left eye with the exact interocular distance you’d have yourself. Many rigs have a much wider distance. That creates a problem with objects that are very close to you in VR. The disparity is too great.

With this solution, we then integrated eight microphones, so the spatial audio is captured as the scene is happening. When I’m talking to you here, I have no reason to turn around. In most cases, the only reason we’d turn around is if we heard a loud sound, say from over in that corner. We’re very good at turning exactly at the angle that we thought the sound was coming from, even though we don’t have eyes in the back of our heads. Our ears are very good at perceiving the direction of sound. We integrated both 3D audio and 3D video because the full immersive experience needs both. We’re rarely moved to look around by an object moving around us. The best cue is always sound.

The way 2D movies tell you a story, they know you’re looking at the screen, and they can cut to a different image on the screen as they go, or zoom in and out as a conversation goes back and forth. In VR the audio is the part that has to make you turn to look at someone else or something else.

The concept is capturing live events. People can go to a place that’s normally not accessible to them for whatever reasons — financial reasons, distance, or maybe it doesn’t exist anymore. If something goes crazy and the pyramids in Egypt are destroyed, we’ll never see them again. But if there’s a VR experience of the pyramids, it would be like walking around and seeing the real thing. You can think of it like a time machine aimed at the past. You capture events and then you can go back and revisit them. In 20 years your son or daughter could revisit today’s Thanksgiving dinner, exactly as you did.

Above: Ozo in a box

VB: Why is this a good move?

Voltolina: It’s very similar to what happened with pictures and video. The first black and white photographs were only accessible to a few. Wealthy people would have family pictures once a year. Now we all have a high-resolution camera in our phones. Video came along and people would hire someone to film a wedding, maybe. Then VHS and digital cameras arrived. But the one doesn’t replace the other. Pictures didn’t replace words and video didn’t replace pictures. We still text. We still share pictures. We still post YouTube videos. Different media for different things.

VR is just another medium. Being a new medium, we focus on how to capture real life in VR. With that, we also have to consider the technology related to carrying and distributing data for playback. After the Ozo we created Ozo Live and Ozo Player. These are software packages we license to companies in order for them to build their own VR players with a higher quality, or to live stream the signal that’s captured by multiple Ozo cameras.

We were at the Austin City Limits concert, for example. A production company there had, I believe, eight Ozos distributed in various positions around the stage. It’s not just one camera. That’s what we were trying at the beginning — the front-row experience, which is great — but I want to go to places I can’t normally access, right? I want to be on stage up there next to Mick Jagger or whoever. I can squeeze thousands of people up there next to him now. In real life, you just couldn’t do that, no matter how much you pay.

Above: Ozo has eight different cameras for VR capture.

VB: How does it differ from the other 360 cameras out there? Facebook showed off a design for one as well.

Voltolina: The majority of the solutions you see announced are a combination of multiple camera modules. Either they have SSD cards or cables. But there’s one SSD card or one cable per camera. If a camera has 25 modules you’ll have 25 SSD cards. When you shoot, you don’t really see what you’re shooting through the camera. Then you have to export all the data, stitch it together, and see what comes out.

One of the big differences with Ozo is that, yes, there are eight cameras synchronized together, but we created a brain that takes all this data and combines it in real time. Ozo’s output is one single cable going into either your storage or a head-mounted display. You can visualize what the camera is seeing and direct from its point of view in real time. It’s like a normal viewfinder. For VR cameras, to be able to see what the camera is shooting in real time is key differentiator.

The other key characteristic is that it can operate as a self-contained device with a battery and just one internal SSD card. You can mount it on a drone, on a car, in different situations where you need flexibility and the size has to be compact. It’s about the size of a human head. The unobtrusive design is a big advantage. Some of these rigs with 16 or 25 cameras become quite invasive.

If you want to capture multiple points of view — let’s say you have a rig with 16 cameras, even small ones like GoPros. What if you need seven of those? What if you need to assemble a hundred and some cameras? One of them might malfunction or fail to synchronize or something. Once you start demanding large numbers of cameras, the delta becomes significant.

Above: Ozo at sunset

VB: How much does each one cost?

Voltolina: It’s $45,000. The development of components that didn’t already exist is what pushes up the price. Cameras, since day one, have been thought of as one lens and one sensor. All the components related to the electronics around it assume you’ll have very high resolution, but only one sensor. When you combine eight together, the SOC that has to coordinate all the sensors — that component didn’t exist. We were forced to create an FPGA to do something that hadn’t been done before. You’re synchronizing all those 2K by 2K sensors at 30 frames per second. The data rate is significant. There were no components that can encode, in real time, all eight streams in one SOC that’s produced at affordable volumes.

Also, the sensor itself — we use a square sensor, which is the best geometry for capturing the fisheye lens. Most sensors are rectangular. That leaves a lot of sensor cells that won’t be used. We also needed all the images to be fully synchronized. I don’t know if you’re familiar with a rolling shutter versus a global shutter, but if you have multiple rolling shutters, the exposure to light is never 100 percent synchronized for all of them. It creates eight images that all have slight differences, and when you stitch them together they don’t match. We had to introduce a global shutter, which has a smaller market and costs more.

The lenses are custom made, because the geometry of the camera didn’t exist before. All the components are pretty much designed for this new purpose. The fact that we don’t already have millions of cameras on the market using them makes those components more expensive.

VB: If it comes out at that price, what kind of users are attracted to it at this point?

Voltolina: We started selling the Ozo in February of this year, in North America. At this point we’ve reached most of the rest of the world, including Europe and China. Our main customers are studios, big and small, that are already producing VR content. People who’ve already tried to make professional VR content or 360 video. When they see the Ozo, they understand the benefit immediately. It’s more expensive, but the savings in time during production — particularly in the stitching and post-production — is so significant that it pays off rapidly.

You can imagine that when you set up with actors on location, you’re spending the most money per hour that you ever will during a video production. If you have one camera where you can see what’s happening and coordinate the actors accordingly — you move here, you move there — and then you have to shoot with another camera, you can’t review what’s happening until later. If you have to go back and shoot again that’s a huge amount of money.

Currently VR experiences are mainly additional marketing for movies, things like that. They’re not movies in their own right. It’s the VR experience of Pete’s Dragon or Jungle Book, features like that. Or a lot of commercials, of course. Live events are big. We’re seeing people experiment with live events almost every week. We just finished up in China for the Strawberry Festival, a music festival, streaming that to several countries.

Above: Ozo

VB: What’s proving the most popular so far? Is it the live streams, or produced recorded content?

Voltolina: It always depends on who’s in the movie. [laughs] It’s not so much about whether it’s live or not. It’s about who’s the star. There was a movie opening for Disney that we streamed, Alice Through the Looking Glass. Pink, the singer, did a concert live for the premiere. Of course that drove a lot of viewers. But we also did a music video with OneRepublic for a new single called “Kids.” They released a 2D music video and then a VR experience. That wasn’t live, but on social media all the fans were really intrigued by the fact that they could watch the video, and then see it from a different direction in VR. Fans would watch it again and again as they discovered new things in the experience. The flow, the story of the whole thing is much more than just the band gathered around the camera.

Another one that was very popular was Pete’s Dragon. In the VR experience you really get to fly on a dragon. You can look around at the wings and the tail. The video itself is like an airplane ride. You’re flying over New Zealand. But the fact that you’re on top of a dragon — for a lot of fans that was a big attraction. It’s always a combination of subject and story. And of course, it helps if you have a major star.

VB: What’s the next step for you? Do you have a road map going forward?

Voltolina: The next steps go in two directions. One is toward a more complete solution. If we’re capturing more and more data, we need to efficiently carry that data to viewing devices, which are getting better and better. Last year was the year of Cardboard. We started seeing the first Oculus and HTC headsets this year. Now we have PlayStation VR, Daydream. Many more devices will be released with higher resolution and better performance. The highest level of immersion keeps going up.

Also, the number of people who are at least familiar with 2D 360 video is going up. That gives more of an incentive to go for immersive VR. The technology to enable Ozo Live or Ozo Player for better immersive playback, that’s currently our next step.

VB: So that’s increasing resolution?

Voltolina: Definitely resolution, but it’s quality in general. Resolution is always mentioned because it’s an easy way to describe better quality, but at some point resolution gets to where you can’t even distinguish. Better visual quality in general is coming, including the quality of stitching. That’s already improved tremendously. With the camera, you get the Ozo Creator software, which does 3D stitching. We’ve released three new versions with significant improvements each time.

Another area is production with multiple Ozos for live streaming. We’ll support a way of producing a VR experience that doesn’t just use one camera. It’ll incorporate commentary, different locations, and so on.

VB: Will you be able to bring it down in price?

Voltolina: We started at $60,000 when we first announced it. By summertime we adjusted to $45,000. The reason is, the first few months we were producing the earliest units and we weren’t sure we could scale manufacturing up to serve the whole world. We started with one region, North America, to see if the product would be well-received, and then if we could scale manufacturing. That happened in August. That’s how we were able to bring the price down. Since it’s professional equipment, a lot of rental houses are carrying it now, too, just like high-end cameras from Sony or Panasonic.

VB: Are the components going to move to move to a application specific integrated circuit (ASIC) at some point, possibly? Do you think you’ll be able to reach economies of scale?

Voltolina: At some point, yes. The trade-off is always volume and time. As you know, for an ASIC to be efficient you need hundreds of thousands of units. You also need a product that doesn’t evolve very fast. If you look at digital cameras, yes, they’re evolving, but they’re not completely changing every generation. Maybe it was like that in the very beginning, but now the technology is stable, and the volume — hundreds of millions of phones with cameras are being produced every year now. The number of VR cameras in the marketplace today — we’re still at the very beginning. As soon as the economics justify the migration to SoCs or ASICs, that will happen.

VB: What’s a good way to measure growth? Can you measure how many hours of VR content are out there?

Voltolina: We keep track of three or four major areas. One is the installed base of the head-mounted displays. We include Cardboard in that, but we’re counting them in a separate category. Cardboard, you never know if someone’s using it. Maybe you give it to your kids and it ends up in the trash. But something like the Samsung Gear VR, we don’t know how much it gets used, but at least you have the capability. And when people start spending $500 or $700, those devices probably get used.

The installed base of high-performance head-mounted displays is important, then. Also, the amount of money going into VR productions. If it’s true that the majority of those experiences are for marketing purposes — marketing movies or products — marketing works if you have an audience. The bigger the audience, the more marketing is interested in addressing that audience. That’s another driving factor.

We also monitor the major VR content hubs, like the Oculus store, Little Star, Disney VR, and so on. How much is out there for you to watch? If you compare to a year ago the difference is astronomical. It’s gone from tens to hundreds, and pretty soon we’ll be hitting the thousands. A good chunk of it isn’t necessarily the most fantastic stuff, but you can see the quality level going up.

The quality of the top VR experiences is getting significantly better. I don’t know if you remember one of the first pieces of content that was popular, but it was a guy playing the piano with his dog. Everybody thought that was great at the time, but if you watch it now, you’ll be bored in less than a minute. So what? The new ones are real stories. It’s not just, “Oh, a 360 video.” Something is happening for you to follow.

A studio called Magnopus — they won an Oscar for Hugo — did a small experience called The Argos File. They won an award for it. That was shot with Ozo. It’s very much an action story, a crime drama. You see things through the eyes of the victim. It’s very fast. Watching that, you realize that this can be really intense. If you like the genre, it’s a fantastic experience.

Above: Ozo

VB: Does this look like it’s going to be a good business soon, or is it still more experimental?

Voltolina: We believe it’s going to be a good business. I don’t think we’re at a stage yet where it’s mature, by far. The best comparison I have is the brick phone, which a lot of people in the industry use. The first brick phones were fundamentally phones without wires. Comparing that to the iPhone, it’s night and day. The best you could do with that brick phone was dial a number and make a call, and the battery would last a couple of hours. Right now we’re at that stage.

Of course we’ll move rapidly to whatever will be the iPhone of VR, as far as integration and features and so on. But it’s hard to even imagine, to a certain extent. The concept that is fundamentally true is that — I grew up in a world where every picture, every video, was a rectangle. IMAX is still just a really big rectangle. The new generation, with Minecraft and other games, but also now with VR video, the rectangle is just laid over 360. All the kids growing up now won’t understand why were so limited before. Why did we never move that rectangle around?

For me, that concept is what will improve VR. Of course, we can’t stick with this form factor. Comparing a brick phone to an iPhone, the form factor is amazing. God knows what will transform this box, this mask on your head — the steps you need to take to go into VR right now are significant. But PlayStation VR is already a huge step forward. The setup is compatible to what’s already in your living room. It works immediately. A lot of the steps are getting smoother. That’s why we truly believe the industry is growing.

If we’re able to participate and remain a leader like we are now, well, that’s all up to us. We need to keep innovating and try things like Ozo. We don’t know everything yet. There’s some level of risk you have to take when you’re the first.

VB: The Sony Pictures deal is hopefully going to create more fresh content.

Voltolina: Absolutely, yeah. We did a deal with the Disney group, including all the studios owned by Disney — Marvel, Lucas, ABC, Disney Nature, there are 13 or 14 of them. That was already a huge step. And Sony Pictures also includes Sony Music. It’s going from movie features to TV shows to music videos. When we negotiate those agreements, we always look at a broader range of entertainment.

We also did a production with Warner Bros. for Major Crimes, the TV show. They used the OZO. But that was for a specific show. When the deal is done with a group, it’s much better, because we can go for many different kinds of entertainment.

VB: Are you seeing anybody start to do longer video productions?

Voltolina: We’re seeing things stretch over multiple episodes. The guy who directed Grease, Randal Kleiser, he created a series called Defrost. It’s 10 episodes in VR. The story is that you’re living the point of view of a person who’s been hibernating, and then he’s thawed out. Your family meets you again, but you don’t remember them. All the acting is around you. You’re in a wheelchair and things happen as they push you through the hospital. Each episode is probably 15 minutes? I can see things going in that direction before they go for 60 or 90 minute features. Live events are already at 60 minutes, though.

VB: What are some of the other ideas people have had for it? I’ve seen views from the top of the arena in a basketball game.

Voltolina: We had a guy climbing Mount Everest with an Ozo. We didn’t even sponsor it. This guy just bought an Ozo and climbed Everest. He re-created the experience of being at camp one and camp two and so on. Of course you have sports, putting the Ozo in the front row, behind the basket, on a race car. People have gone to fantastic locations, like inside a volcano in Guatemala.

The different compared to a normal documentary is that you have that freedom to look around. Of course, a story still has to be told. The experience has to be entertaining. If it’s just silent, it’s pretty boring. If you’re alone in the jungle, just walking around, after a while you lose interest. But if there’s somebody talking about things that you can look at, while you still have the freedom to look where you want, that’s much more entertaining.

For the news, you can imagine — if you’re in the middle of an event where even the journalist doesn’t know exactly what’s happening, having a document where you can look around without the limitation of a cameraman deciding where you can look, that’s huge. You can revisit an event and find so many things you never saw before. You have the whole set of data.

Above: A scene from Start VR’s Awake.

Red Bull is doing a lot of VR, of course, extreme sports and so on. Locations, news, live events, music — you name it. The VR experience isn’t a substitute for video, though, which is interesting. It’s complementary. Say you come to my house to watch a game. We’re watching the screen together, and then someone on social media says, “Check out the home team’s bench.” Then you can go in VR and see what’s happening there while we still watch the game on TV. It doesn’t always have to be a substitute.

VB: I like the way VR audio works, how audio draws you to a particular point of view.

Voltolina: Definitely. We believe that’s half of the feeling of being present, that it’s driven by audio. If you just use stereo audio, or a mix that’s not accurate, it’s not the same.

VB: I do wonder where the technology is going to settle. Some of the early cameras had something like 36 modules. Why not use that many? Is that necessarily better?

Voltolina: The compromise is always the amount of data versus the benefit you get from it. We have eight cameras with a lot of overlap to create two layers of pixels. But we stop at a certain amount of data, because we wanted the live monitoring. We want a work flow that’s doable in real time. It’s a bit like those cameras that can capture a really high number of megapixels, but then you need to transfer the data in a certain way before you can see the picture.

Also, it’s the number of seams. If you increase the number of cameras, it’s true that you’re capturing at a much higher resolution, but then the number of seams you have to stitch is much higher. If you look at the wall over there, at that panel with the seams, if I just had one big piece of glass it would look better. But of course the cost is a tradeoff, having a big piece of glass that’s hard to transport compared to a bunch of little ones. More seams adds much more heavy computation. And if the seam cuts through an interesting part of the video, my brain will pick up on it right away. I’ll look right at it, and after that I can’t ignore it.

We compromise with our number of cameras because we want some flexibility in where the seams go. If you have a very high overlap, I can choose to position the seam at different degrees. I can dynamically change it so that if a person’s face is right on the seam, I can shift it to the left or right to avoid that problem. But if there are too many seams, as soon as I shift it to the right it’ll impact the other ones nearby. This gives you more space for that flexibility.

Above: VR Days Europe attendees in demo mode

VB: What about the difference between applications? You have Hollywood cinematographers, consumers, GoPro enthusiasts. It seems like different cameras will be useful for different people.

Voltolina: If you start from the top of the market, that’s where money and time is available right now. If I’m at the top, I can shoot and perfect my product very well. But it also means the data I’m capturing has to be the best data possible. I can extract every single drop out of that data because I have time and money.

As soon as you become more limited in your budget — by which I mean both time and money — then the number of people operating in a smaller crew — it’s not that they don’t follow the same steps, but each person winds up with two or three roles. In a big production you have a cameraman, a lighting person, a sound person, assistants, and so on. A smaller team, maybe five people, one person will be the director and DP, another will do sound and light. That means that the product has to be able to do more things for more roles, all integrated.

Then you go all the way down to the one-man band. A news freelancer out there in a war zone, a guy who films weddings, or a guy who does educational videos for corporations. These might be $5,000 to $15,000 productions. Certainly not millions of dollars. But they need to work fast, because they need to make that money in a week, not over six months. The setup time becomes very important. Fast stitching and turnaround is very important, because they need to be able to show it to the customer, get an approval, and get paid.

Ozo, right now, is reaching the independent production stage. But for the one-man kind of production — it’s practically usable by one person, but the price is still significant. If I do weddings, I might rent an Ozo for one job. But most likely I wouldn’t own one yet. At some point I might line up enough jobs to make the investment and have that as a differentiator for my customers. Even if you’re not shopping for a VR experience, you might go to the guy who also does VR experiences because that shows that he’s the most technically advanced. It becomes a marketing hook for professionals.

The market for 2D 360 video and VR experiences is rapidly expanding. But they’re still nowhere close to regular video. Like I say, we’re still in the brick phone era.

VB: It sounds like a fun territory to be in right now.

Voltolina: It’s very interesting, yes. The part that’s most intriguing to me is this area where we can watch the same video and have a different experience. I can share something with you that, even if we both watched the video, you haven’t seen. A third person could come in with something we both haven’t seen. From a social exchange point of view, it’s fantastic. If we’ve all seen it once, that doesn’t mean we’ve any of us seen the same thing. Maybe I’ll try to watch the way you did a second time. It becomes a very interesting mechanism.

VB: Do you have any news coming up at CES?

Voltolina: We’ll keep you posted. [laughs] We’ll have some news. In general, we’ll have ongoing updates all year long, because we’re working on so many different fronts. We have the camera, the Ozo Live software, the Ozo Player, other technology to enable better viewing and stitching and live streaming. The last announcement on Ozo Live, for example, added support for multiple cameras. That’s a huge step.

VB: How big a part of Nokia is this? How many people are working on it?

Voltolina: A few hundred. Nokia Technologies overall is 800, 900 people. That includes digital health, digital media, and the licensing team. But we’re definitely expanding. If you visit our website, we’re hiring talent.

VB: Where is most of the work done? Is it Finland?

Voltolina: The majority of the R&D is in Finland. That’s where the project started. Now it’s maybe 65 percent Finland, 35 percent Sunnyvale. Sunnyvale is expanding. But it’s so competitive here. There’s a lot of VR expertise and a lot of VR investment. The expertise becomes a scarce resource. It’s like any wave of technology in Silicon Valley. As soon as everyone identifies a new wave, the highest concentration of investment is here and there’s a fight over the rock stars.

VB: What about augmented reality? Are you looking into that?

VB: What about augmented reality? Are you looking into that?

Voltolina: Definitely. AR is another area, though. AR has two meanings now. One is AR on your real surroundings, but there’s also AR video capture. As you can imagine, I can capture a video of a certain area and do AR not necessarily on what’s around me, but what’s been captured. That area is extremely interesting. It’s not just like subtitles or overlays, additional data that’s embedded in a video and it’s the same every time you watch it. With AR you can do it dynamically.

Again, you watch the same video, but depending on how you look at it or how you control it, different information can be overlaid. You can do that in a more interactive way. Every time you watch it you discover something new, extract different information. Up to a point of augmenting something that wasn’t there. What if something else was happening? But in an interactive way. What if I watched a recording of a meeting, but with different people there? Or the room was different somehow. All kinds of things.

You can see a convergence happening. There’s computer-generated VR and recorded VR. But you can easily imagine mixing those two together, in particular when the playback platform is the same.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More