Supercell has outstanding mobile games, but it’s also known for killing off the projects that don’t work.

The Helsinki, Finland-based company is known for games such as Clash Royale, Boom Beach, Clash of Clans, and Helsinki. These games have generated more than 100 million daily active players, and that track record is why Tencent bought 84 percent of Supercell at a $10.2 billion valuation.

But Supercell has just 210 workers, and it is trying hard to recruit talented people to Finland. So that is why Timur Haussila, game lead at Supercell, gave a talk about how the company runs at the Montreal International Game Summit today.

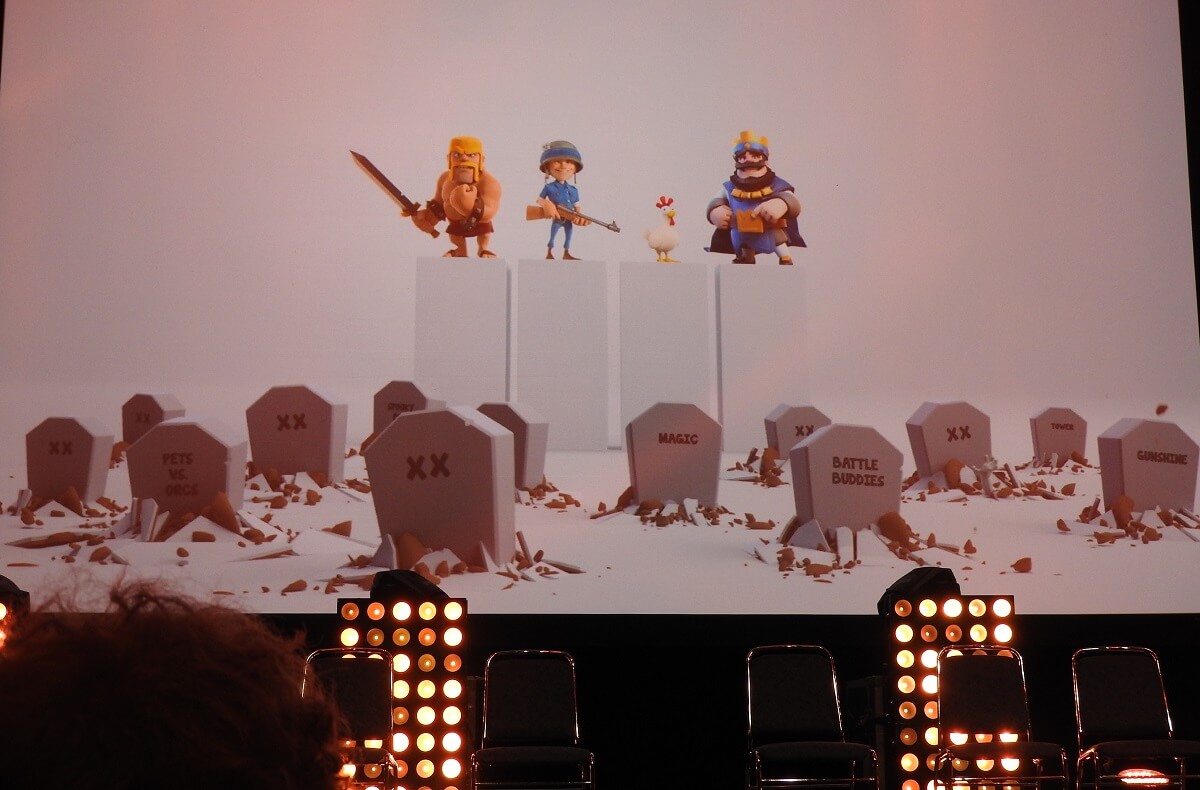

Haussila described how the company’s structure puts control of decisions, such as whether to publish a game, in the hands of its small teams, or cells. While Supercell has four published games, it has killed 14 in various stages of development. One game, Smash Land, died after nine months of work and an early release in beta form.

Above: Supercell has killed 14 games and published four.

That may seem like agonizing decision-making, but it’s hard to argue with the results. Haussila has managed to get two of the company’s games out. He worked on Hay Day, and later Boom Beach. Both are enduring hits.

Haussila joined Supercell five years ago. Prior to that, he worked under a more traditional structure for building games at Digital Chocolate. There, the creative process worked from a top-down perspective, where a leader or executive had a vision for a game and translated it downward. The executive team plans its portfolio and directs the teams to work on its directives. If the work is good, the executives greenlight the games, or they kill the work done by the developers.

“We started to game the system,” Haussila said. “The goal was not to make the best game, but to play the system. The goal was to get the product through the review. When the review was happening, you sold your idea to the people in the group. That was a distraction.”

One of Haussila’s teams, working on Zombie Land, managed to get a game out because there were executive changes and, while the team wasn’t really trusted, no one was really supervising it closely. When it started generating revenue, the executive attention returned and killed the creativity, Haussila said.

Above: Traditional game design.

Supercell set itself up differently. Under CEO Ilkka Paananen, the company organized itself by cells of five people or so, with major decisions staying within the cell. The game leads and CEO were there to serve the game developers, helping them succeed and deal with tasks such as hiring.

“I decided to join the company even though I didn’t enjoy the game they were working on,” Haussila said. “It was upside-down, from the bottom up. The vision holders are the game developers. The CEO at the bottom is the enabler. The superstars are the ones that take the risks and lead the company.”

But the self-regulation of the cells means that the teams are responsible for killing their own ideas. Many games are prototyped and killed at that stage. Fewer make it to company-wide testing, and another culling limits what goes into beta tests in limited countries.

Above: Supercell’s team structure.

Haussila believes that Supercell’s method can scale. The cells could be in Helsinki, or they could be in other countries. The only rule governing them is they need to be self-sustained. Some teams are led by an artist, others by programmers, product managers, or designers.

To make the cells work, management has to trust he team. The teams operate independently, and they are responsible for their own work. They focus, and they emphasize speed and quality.

“Trust has to be mutual,” Haussila said. “If you take a risk, fail, and get fired, then the system doesn’t work. We don’t micromanage what you’re supposed to do.”

Above: Where Supercell kills its games.

For a time, Supercell created what it called a “safety net.” If a team canceled a game, and they had no project for a while, they could go work on prototypes in the safety net. But some developers stayed in the safety net too long. And those developers felt uncomfortable. Supercell found ways to get them on teams.

During the development of Boom Beach, Haussila felt the team was lost. It was funny, but systems were confusing and some wanted to kill the game. The team believed in the title and kept working on it. Smash Land, by contrast, was killed after the team honestly decided if they wanted to keep working on the game for the next two years. But teams often have to take the responsibility of thinking of what is good for the company. The company salves the wound by celebrating its failures with talks about the lessons learned.

“You don’t need to be afraid of failing,” Hausilla. “You put your heart and soul into it for a year. You find out you were wrong. That feels tough. You can’t blame anybody.”

Disclosure: The organizers of MIGS 2016 paid my way to Montreal. My coverage remains objective.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More