Sometimes, the advantages of a new technology are unclear because people are evaluating it with an outdated metric.

Case in point: miles-per-gallon-equivalent (MPGe) ratings for alternative-power cars, including hybrids, plug-in hybrids, and electric cars.

This has become clear to me over the past few months since my family started driving a plug-in hybrid. We’re saving an enormous amount of money by driving on electricity instead of gas, but none of that savings was obvious before we bought the car.

Traditional miles-per-gallon ratings have been a key part of automobile marketing for decades. Indeed, it’s one of the things that dealers are required to put on the window stickers for new cars.

But how do you handle a car that consumes fuel by the kilowatt, not the gallon?

The misguided MPGe

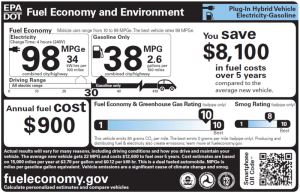

The Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Transportation addressed this with the MPGe figure, which has been mandatory on window stickers since 2011. But this rating is artificial, and it doesn’t actually help buyers estimate the true impact of buying an electric or plug-in hybrid car.

What does it mean that an electric car like the Nissan Leaf has an MPGe of 126 city/101 highway or that the Tesla Model S gets 95? These cars never consume gasoline at all, so those figures are purely imaginary. It’s hard to translate these numbers into a measure of what the economics of the cars really are.

More helpful are the figures in smaller print next to the MPG ratings: kilowatt-hours (kWh) per 100 miles on electricity and gallons of gas per 100 miles on gas. But few consumers know this data exists, let alone where to look for it or how to use it. (Complicating things: The fact that this is stated in amounts per 100 miles instead of per mile.)

In my case, my family’s new car is a 2014 Toyota Prius Plug-In. In the past few months, we’ve seen an average fuel economy of about 45 mpg, a little off the official efficiency of 50 mpg in hybrid mode. Our driving includes a combination of around-town trips (taking the kids to school, shopping, errands, and so forth) and one long-distance jaunt for a total of about 3,500 miles.

In its plug-in, electric vehicle mode, the Prius has an official MPGe rating of 95. Sounds pretty good, right? But what that actually means depends on your use case.

Its range on purely plug-in electric power is small: just 10 or 11 miles. That’s not much for most American consumers, but it’s plenty for us most weeks. I commute via bike and train, and my wife works at home, so the car’s main uses are for taking the kids to school and running errands.

The upshot: Many days we burn no gas at all, or almost none. We plug in the car overnight, using a standard 110-volt outlet on the porch (as with most electric cars, the Prius charges just fine on household current). Using the Prius’s capability to schedule its recharge for specific hours, we have it recharge in the early-morning hours, before 6 a.m., when the rates are the lowest.

What driving on electricity actually costs

It takes about 3 kWh to recharge the Prius. At PG&E’s early-morning rates on our tiered plan, that’s about 20 cents to 25 cents’ worth of electricity. (Hint for northern California readers: PG&E offers a special plan for electric car owners, but the rates aren’t actually that good. Its best rates are available through its Time of Use plan, which charges higher rates during the day but very low rates overnight.)

As a result, the economic impact is substantial. Ten miles in our old car, a 6-cylinder Mazda minivan that gets 20 mpg at best, takes about half a gallon of gas, which at California’s current gas rates costs us about $2.10, or 21 cents a mile.

In the Prius, burning gas, 10 miles costs us about $1.05, or a little more than 10 cents a mile.

But on electricity, that 10-mile all-electric range costs no more than 25 cents, or under 2.5 cents a mile.

In other words, on a cost-per-mile basis, electricity is roughly one-tenth the cost of gasoline.

Clearly, this gives us an enormous incentive to run the car on electricity instead of gas. We’ve been able to save about $60 per month this way. Add in the savings from the increased efficiency on gas-powered driving (compared to our old car) and our savings are over $100 per month, or almost half the cost of the car’s lease.

The savings would be less if our daily driving range was longer, as it is for most American families, because the cost of electricity would become a smaller proportion of our overall driving cost.

As a result, enhancing the plug-in range will be critical for Toyota if it really wants to sell more plug-in hybrids.

Regardless, none of these economic advantages are obvious to most car buyers, since the MPGe rating obscures them.

Complexity and opacity rule

Adding to the complexity are fluctuating gas prices, introducing uncertainty into the cost-per-mile calculation for internal-combustion driving. And electricity prices are not only variable, they are not at all transparent. You can’t look them up on PG&E’s website. So it is almost impossible to make this calculation until you actually drive the car home and try it out for a while and then look at your utility bill.

No wonder electric cars and plug-in hybrids are not taking over. As long as outdated means of measurement obscure their true economic impact, and as long as the market for electricity remains so opaque, few people will be able to figure out whether they’re worth it.

If the EPA wanted to make a meaningful difference, it would force some transparency into electricity pricing and mandate estimated cost-per-mile calculations on window stickers instead of MPGe.

Better yet, it could create an app that people could use to perform their own calculations based on their location, utility company, and the current price of gas in their area.

Or, even better, car manufacturers like Toyota, Nissan, and Tesla could make their own apps to simplify these calculations easier for would-be purchasers.

The good news is that electricity-powered driving is very much worth it — if you can buy a car whose range fits your needs.