One thing that some of the biggest games in esports share in common is that they don’t change that much. Sure, they have updates and new characters, but the basic gameplay stays the same, and that allows for the cultivation of celebrity teams and athletes over time.

That means you have to get the design right the first time, as happened with games like Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and League of Legends. And if you’re going to change your title every year, as Activision does with Call of Duty, then you have to carefully consider the impact on esports.

I recently attended the Intel Buzz Workshop: The Future of esports in Los Angeles and moderated a couple of panels. One was on the evolution of esports, and the second was on designing for esports. My panelists included Rod Chong, chief operating officer at Slightly Mad Studios; Alessandro Avallone, cofounder of Faceit; and Michal Blicharz, vice president of pro gaming at ESL.

We talked about the trade-offs in designing for esports and general consumers. And we also went into the topic of retrofitting games so that they can be used in esports competitions. (The Intel Extreme Masters esports event is happening this weekend in Oakland, Calif.).

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

Above: (Left to right) Michael Blicharz, vice president of pro gaming at ESL; Alessandro Avallone, cofounder of Faceit;

Rod Chong, Slightly Mad Studios; and Dean Takahashi of GamesBeat.

Rod Chong: I’m from Slightly Mad Studios. We make Project CARS, a simulation game on PC, PlayStation, and Xbox. Our world is a bit different because it’s focused on sim racing. Some elements are unusual. Sim racers develop esports skill sets that can actually translate to professional car racing, which is a different pathway to what’s available, but we’ll get into that.

Alessandro Avallone: I’ve been in professional gaming for more than 15 years, playing many different titles. I’m one of the co-founders of Faceit. I’ve lived esports since back in 2000. I was very young back then, but I’m still here, 16 years later.

Michael Blicharz: I’m the VP for pro gaming at ESL. Chiefly responsible for the Intel Extreme Masters circuit, which is in its 11th year of running. We run stadium esports events around the world. ESL organizes competitions from casual online events all the way up to very large events with thousands of people in the stadium and large cash prizes.

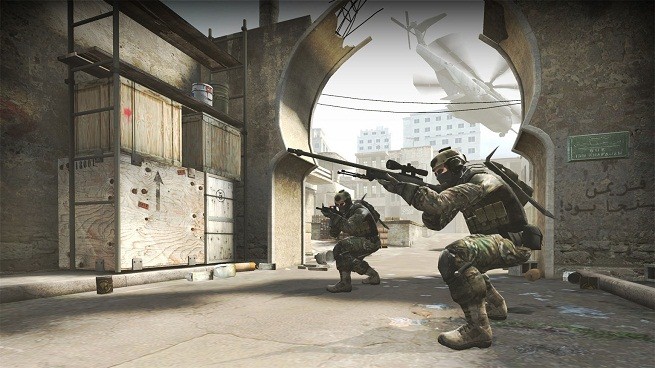

Above: Counter-Strike: Global Offensive.

GamesBeat: I interviewed Minh Le, who created Counter-Strike 18 years ago. He explained that the beauty of Counter-Strike is that it hasn’t changed. People who played it then know how to play it now. It’s had time to create people who have really refined skills. The challenge for a franchise like Call of Duty is that they’re trying to change the game every year, so fans keep playing it. Call of Duty could have a group of really talented esports players one year, but those players might fall behind and disappear the next year. You never develop the celebrities that are out there. What do you think of that particular challenge?

Avallone: I think it’s correct to some degree and untrue to some degree. If you look at League of Legends, theoretically, it’s the same game, but it’s changed dramatically from what it was to what it is today. Multiple patches, multiple balance changes, multiple new champions, things like that.

It’s good for esports overall if the game is built to have longevity, certainly. It’s never good to have a brand new title that feels completely different. If you want to build a good game, it needs to change a little bit. It doesn’t need to change dramatically, but it needs to evolve. In Korea, in the first StarCraft: Brood War leagues, they’d constantly change the maps the game was played on. That changed the players’ strategies and approach to competition on those maps. The same thing is going on in Counter-Strike these days. Counter-Strike is tweaked a bit, with maps that are swapped out. That keeps the game fresh. It’s still the same physics, but the strategies have to develop all the time for new maps. That keeps it interesting.

Blicharz: When it comes to Counter-Strike, a game we’ve seen since early 2000 — in terms of mechanics and gameplay, yes, it’s almost the same. It’s changed a bit, but the changes have come over time. Players have been able to adapt. Some of the maps that came out in those days are still used today. They’ve had small changes. The graphics have changed and gotten better, but the mechanics are almost the same. That’s given longevity to the game, the ability to build stars.

Chong: At game studios, you have a lot of people in control of games, whether they’re creative directors or executive producers and so forth. They may think about games from a single-player perspective, career flow, and so forth, which is a traditional way of looking at game design. Then we have all this buzz around esports in the industry. Esports this and esports that is right up there with VR this and VR that. You have this wider trend where everyone’s interested. But within that you need a creative team developing your game that understands how to design a game from the ground up that’s going to work with the needs of esports.

Above: Note the way the car on the right is nudging off the road entirely to avoid contact.

With Project Cars, we started designing the game about three years ago. Our creative director is very bullish on esports. He made sure we had a reasonably good feature set, but still, when we launched the game last May, it was missing some features that we needed. The main thing we were missing were broadcast tools, so you could send an exciting feed out to Twitch and so forth that people would want to watch. The default setup was OK, but some major things were missing.

If we look at a higher level now, at game publishers and game developers and so forth, a lot of them know that they should do something with esports. I’d imagine every publisher and marketing team and creative team out there is racking their brains, thinking about how to make their game esports-friendly. But culturally, you need to design a game from the ground up. That may mean setting aside some traditional single-player thinking.

Right now, I see a lot of legacy thinking within marketing teams. We work with Bandai Namco. Some people in our publishers understand this stuff, and some people are thinking completely differently. It’s a moment of transition right now.

GamesBeat: What do you think about the beginning of the process, designing for esports?

Avallone: It does need to start from the beginning. Whenever you build a game, you need a vision of the gameplay you want. It’s very important to develop mechanics for players in a way such that you can make sure that whenever players compete at their best, they can show it off. But at the same time, it needs to be accessible for those who want to start. You have to look at a bigger picture there.

A big question related to mechanics is what skill set you’re going to require for a particular game. It doesn’t matter what the genre is. It could be FPS or racing or RTS. Whatever game you build, you need to understand the mechanics behind it and make sure that players can start from the bottom to become stars. And when they do, they need to be able to show that off. If you have a game that doesn’t let players improve, there’s something wrong with your mechanics.

At the top, esports is what you see in the stadiums and on the streams. But you need to make a competitive game first, a very competitive title. People need to be able to have fun playing solo or playing with friends. You need to think about an ecosystem. You need to build a strong competitive community that can follow the game, watch other players, learn the mechanics, play together, and work their way to the top.

Above: Battlefield 1’s flamethrower in action.

Blicharz: Number one, before anything, you need to build a game that’s fun to play and fun to watch other people play. It doesn’t necessarily have to be fun for a complete outsider to watch. If you watch Dota for the first time, you’re not going to understand what’s going on, but that doesn’t make it a bad esports game. If you look at, say, BlizzCon as an example and the events there, the relationship between how understandable a game may be and the viewership for that game is quite random. One of the biggest games is Hearthstone, which isn’t enjoyable to watch at all if you don’t play it.

But the interesting thing right now about building a good esports game — all the game developers I’ve talked to, I’ve learned a lot from them that I didn’t know, but I’ve never met one that I didn’t think had something to learn from me as a player. I used to be a competitive player — not quite as good as Ale here, but I picked up a lot of knowledge and understanding. In the industry, the magical formula of how to build an amazing game title is still unknown, still somewhat random. To use Quake as an example, the earliest iteration was probably a better competitive game than the later ones. Publishers, developers, and players themselves still don’t necessarily know how to make that perfect competitive game. We still don’t have the perfect esports game out there yet.

Chong: We’re partnered with ESL for our weekly races. We spend a lot of time talking to our account manager at ESL, learning about what’s working and what’s not working, looking at the analytics with them. It’s definitely informing the design decisions we’re taking for Project Cars 2.

One other thing I’ll say, you have to set up your organization — not only the dev team but community management team, esports community team, and social media team. They all have to work together as a single unit. You have to put people in place who will run point with players. You have to have a very clear, professionally published set of rules, especially when disputes come up. This is a highly competitive environment.

You have to look seriously at anti-cheat systems. We run into that a fair amount with racing titles. Sometimes, people will pick up exploits to make their cars faster. Teams may have one driver that’s better than others, so they’ll do all the lap times in a time-trial event. A fair amount of policing has to go on. We have to update our esports rule set from season to season and change things as we go on. It’s an organic process.

The design team on the game should be reasonably humble. This is a growing area. The goalposts are continually moving and changing. You have to be able to take feedback from players, esports organizers, and everyone in the field that you work with.