When the world shifted from desktop to smartphones, one thing didn’t change: the existence of a screen on both devices.

The screen shrank, but it remained the medium through which we interact with computers.

For Google, that meant its core online advertising business — visible search ads on a webpage — remained intact and lucrative.

Today, Google may be at the beginning of a new shift — one toward artificially intelligent virtual assistants, in which we use our voice to interact with technology instead of our eyes.

The problem with voice assistants is they don’t have a screen on which to display ads.

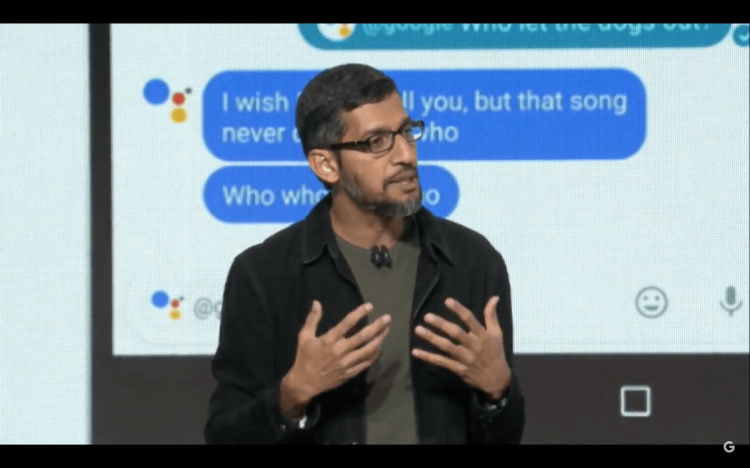

And analysts have noticed. On the last earnings call for Alphabet, Google’s parent company, analysts repeatedly asked Google CEO Sundar Pichai whether voice searches would be harder for the company to monetize with ads. Pichai didn’ have a specific answer, although he reassured investors that he believed the new medium would expand Google’s business.

Virtual assistants, which are basically voice-activated mini computers, are becoming increasingly intelligent and accessible. A spokesperson for Google told Business Insider that its mobile voice searches tripled between 2014 and 2015.

Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortana, and Google’s Assistant are competing to become the most intelligent digital helpers in the virtual assistant race.

The hardware surrounding this technology is expanding, too — Amazon and Google have each released a mini Wi-Fi speaker for the home. You can tell the Amazon Echo or Google Home to play music, look up recipe ideas, find local restaurants, and do a variety of other tasks.

The side effect of all of this is that in the short term, the available real estate for ads will shrink. You could insert sponsored suggestions into a voice assistant’s answers, but it would never offer as many ads as a Google search results page.

It’s a side effect that analysts want to know more about.

Brian Nowak, Morgan Stanley’s internet analyst, asked Pichai on the earnings call to talk about what the company might need to put in place to “monetize search in a voice world as well as you do in a phone or desktop world.”

Pichai responded without directly answering the question, saying “we are in very early days,” that one team “talked about” ways to integrate third parties, and that he thinks “we will evolve it a lot in the coming years.”

Peter Stabler, a senior research analyst at Wells Fargo, asked Pichai if voice queries are “much more skewed to less commercial activity”?

Pichai said that instead of replacing search on desktop and mobile, voice search provides an additional way for people to interact with Google. “The sum total of all of this: It expanded the pie,” he said.

While voice search might indeed expand the pie, history shows that legacy media businesses are often vulnerable to new media tech.

The newspaper business has struggled to adapt to the internet. Many newspapers have closed, and entirely new digital news organizations have flourished in a business once dominated by paper products. Similarly, the television business is fighting fiercely against video-on-demand over the internet.

From that perspective, screen-based search starts to look like a legacy media business, and voice-based search like a vast, open arena with no dominant players. That is exactly the kind of market that new tech startups seek to disrupt.

Google, of course, has a track record of solving complex problems and monetizing products. Four years ago, there were worries it might stumble on the transition from desktop search to mobile search. In 2012, the company actually warned that mobile was hurting revenue growth. Since then, Google has gone from strength to strength, and it remains the dominant search engine on mobile screens.

Google is no doubt thinking about these issues already and developing plans to enhance its dominance. But until those plans are unveiled, these are the three questions analysts would really like Pichai to answer:

- How big a slice of consumers’ internet time will voice search take?

- Will that slice be big enough to significantly reduce the number of searches done on mobile and desktop screens?

- How easy is it to generate revenue from voice assistants?

Disclosure: This author used to be a Google employee and currently owns Alphabet stock.

This story originally appeared on Www.businessinsider.com. Copyright 2016

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More