Editors note: We’ve tried to remove most of the story spoilers in this interview.

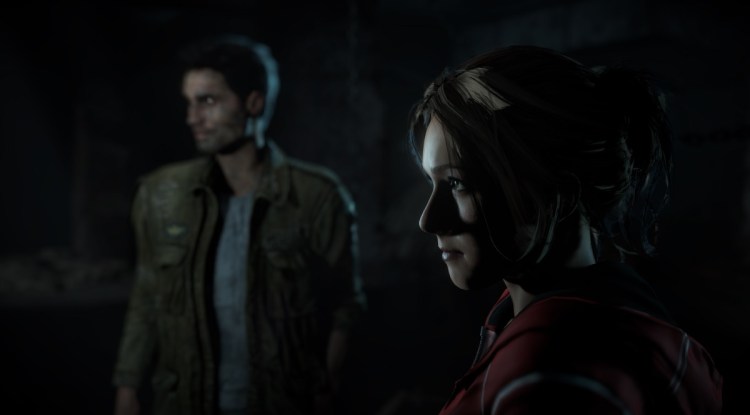

In Until Dawn, the interactive horror game is what you make of it. Based on the chaos theory of the butterfly effect, where a small change or decision can have a very large downstream impact, Until Dawn forces you to make split-second life-or-death decisions about eight young adults who are trapped at a mountain lodge.

The title debuts in North America today as an exclusive on the Sony PlayStation 4. We think that it’s one of the best collaborations of Hollywood and video games to date, with a lot of different branching stories about each of the main characters. Your job in the game is to make decisions that enable each character to survive the night. It is a very different kind of horror tale than you’ll see at the movies on a Saturday evening.

Hollywood writers and directors Larry Fessenden and Graham Reznick wrote the story of Until Dawn, with more than 10,000 pages of dialogue. It took that much writing because any of the eight characters can die. That means each character’s part of the story has to be like a main storyline. We played the game all the way through a couple of times and interviewed Reznick about how he and Fessenden approached the writing and worked with the video game designers at Supermassive Games.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview. Read our review here.

GamesBeat: One thing I didn’t know about was your background in writing game narratives. Can you talk about that, as it compares to Hollywood work?

Graham Reznick: This is actually the first game I’ve written. We started this project in 2011. Technically the Until Dawn that’s being released is the second game I’ve written. The first one was the Until Dawn for the PS3, which wasn’t released. We started it as a PlayStation Move project, wrote it, and worked on it for about two years. Then it was decided that we’d scrap that version and go to PS4, and we decided to rewrite everything from scratch. The technology allowed us to do far better facial animation, which meant the acting could be more nuanced. We could tell the story through a more cinematic style of dialogue.

My background is primarily film. I’m a writer and director. I’ve done a lot of sound design, music, and so on.

GamesBeat: What was attractive to you about the project? It seems like one of the unique things about this is the butterfly effect. I’d imagine that causes a lot of branching in the narrative that you have to write around.

Reznick: Definitely. That was a big draw for me. This came about because my co-writer on the project, Larry Fessenden – the head of Glass Eye Pix, which is the company myself and a lot of my friends make movie for – had been approached by Supermassive. Larry doesn’t have a history with games. He didn’t grow up a gamer. But he knew I did, so he brought me on.

We wrote a bunch of tests, sample sections of the game. We didn’t know anything about it or what it was going to be. We just had some test specs, assignments to write. We were immediately attracted to the approach Supermassive had, what Will Byles and Pete Samuels had come up with. It was very similar to a cinematic approach, and similar to the Glass Eye Pix ethos. They weren’t making this type of horror game for cynical reasons. They wanted to make the best stories they could in the best way.

As far as the butterfly effect and the branching narrative, as a filmmaker and a screenwriter, you sit down with a character and a story, and then you immediately think of every possible version of that story at any given moment. You’re trying to find the best path for your screenplay. If a character has to go to the store and buy a loaf of bread, there’s a million ways that can happen. Who’s he gonna run into along the way? Does the store get held up when he gets there?

Writing the game is basically the same, but all those different weird little pathways suddenly become additional scenes that you have to write in tandem with the main story. Or what you hold onto as the main story for a little while, until you start realizing, “Oh my God, they’re all main stories.” It’s like writing parallel universes, which is—I’m a big science fiction fan, so that appealed to me.

GamesBeat: The combinations seem mind-boggling. If you have 16 characters, I imagine that the number of lines of dialogue you have to write just multiplies and multiplies.

Reznick: It’s insane. We have eight main characters, and they all can live or die at various points in the game. You can finish the game with them all alive, all dead, or any permutation in between. It’s not just whether they’re alive or dead that changes the narrative. Little choices you make change the personalities of the characters in interesting ways, which then has a ripple effect throughout the narrative. There’s all these things that can completely alter the path through the game.

I don’t know for sure how many pages are in the final PS4 version, but between the two versions there have been more than 10,000 pages of dialogue written. It’s been pretty intense.

GamesBeat: Now let’s bring up the analyst. At the end of each episode, you have a conversation. You don’t know who the analyst is talking to yet. He talks about how you’re playing the game. It made me think that he was talking directly to me, the player, rather than the psycho in the story. That ambiguity was very interesting. It made it suspenseful, but it also layered in different messages. I wonder if you could talk about that a little.

Reznick: The analyst in the game is an interesting device. It came later in the process, but it’s something we were always thinking about. In a sense, the analyst stands in for the video game designers and the writers, that part of our persona as we’re creating the game.

Last year, when the game was shown at Gamescom, or maybe it was more than a year ago, the developers put a little survey in front of the game asking about people’s fears. That was so the demo could get some information to help us understand what we should do as we were finishing the game. But it was so impactful for the player to feel like they were having an effect on the actual tonality of the game, more than just the narrative – as if it were catered to them. Will Byles realized that should be part of the game.

GamesBeat: There was a time, maybe in the beginning, that I felt as if I was the puppet master. And then you find that there’s another character who’s the puppet master. But at various times, especially when you’re doing something like a jump scare, I feel like you’re the puppet master. The writer is manipulating the player.

Reznick: Here’s an interesting way to look at it. When you’re making a movie, everything is very static. You show the audience one specific story, the story the filmmaker wants to show. That’s how the artform, the medium of film, works. It’s great, and there’s a million different ways to explore that.

What’s exciting about games, and specifically narrative-based games, is that you can take that approach from filmmaking, the curated narrative, and then explode it out so that the designers and writers of the game are curating a narrative environment for the player, but the player becomes a complicit collaborator. The interplay becomes very interesting when the player is not sure exactly what all the pieces are. It’s like you’re moving chess pieces around on a board, but one of those pieces can suddenly melt and turn acidic, or one of them can explode and blow up half the board.

It’s kind of like real life in that way. You move through life trying to make your way through your environment, and you think you know what’s going on sometimes, but people can surprise you. Little things you do have impacts on the environment and the milieu around you. Our biggest goal with this was to make sure the player could weave their own narrative through a larger meta-narrative that we created, but that it would always be satisfying, no matter what happened.

That was the biggest challenge. You can get to the end and all the characters will be dead, but it’s still a satisfying story. You’ll still get the full nine-plus hours of gameplay and narrative.

GamesBeat: There are parts where it seems like the choice is not always easy or clear. It almost seems random. How much choice is built in to the game? You could go left or right, and if you go left, you die, and if you go right, you live. That sort of thing.

Reznick: Part of it was we didn’t want it to be super cut and dried at any given point, so you could say, “I’ll be the good guy here. I’ll be the bad guy there.” You just have to make choices. Almost all the choices you can make should be informed, to an extent. There are some more or less random ones in there, but I don’t remember exactly what all the choice points are. The majority aren’t so black and white. Some of them are.