It’s rare to get a chance to meet someone truly different. Phil Tippett is one of those people. He has been creating monsters for the movies — including the memorable Holochess game in the original Star Wars film — for more than three decades. He reprised that work for Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens. And that inspired him to make monsters for a new augmented reality mobile game, HoloGrid: Monster Battle.

I traveled to Tippett Studio in Berkeley, Calif., last week to view a demo, which is unlike anything I’ve seen before. It is a hybrid of a board game, a collectible card game, a mobile game, and an augmented reality game — all in one. The game from HappyGiant features monsters designed by Tippett himself, a two-time Academy Award winner for Star Wars: Return of the Jedi and Jurassic Park.

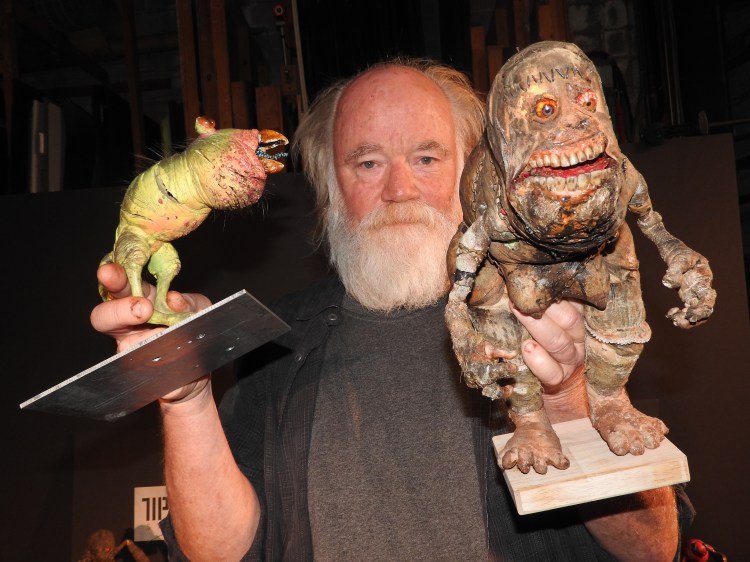

Tippett created sculptures of the creatures, which his team then captured through a technique dubbed “photogrammetry” and converted into digital form. Then computer animators took over and made it so they could move. The results are some highly original, realistic creatures that don’t look like they were designed for a video game. HoloGrid is on display this weekend at the Google Play Indie Games Festival. I caught up with Tippett at his zany workshop.

Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

Above: Tippett Studio and HappyGiant are using handcrafted monsters in HoloGrid: Monster Battle.

GamesBeat: Quite a playground you have here.

Phil Tippett: Yeah! Our demented Santa’s toy shop.

GamesBeat: The creatures you created for this, can you talk a little more about them? Did you have anything in mind for a long time?

Tippett: Some of them I made more than 30 years ago, starting with the Mad God project. Some of them were also ideas I had for feature films. I’d come up with some designs and work with writers and go to Hollywood pitching ideas for things. They’d say, “Nah, we don’t want to make that movie,” so I have a bunch of these things on the shelf that I’ve collected over the years.

That’s what gave the impetus for Mike. What he needed to do to get his Kickstarter going was have a proof of concept. He said, “Have you got anything?” I said, “I’ve got a lot of things. Come on in. It’ll be like shopping at Safeway.” It goes back so far. Some things I made for movies that never got made. Some things I made for Mad God. Some things I’d just do on a rainy afternoon with my kids. We’d do little sculpting projects. I’d make something and they’d see how I did it. It runs the gamut. A lot of this stuff was just in boxes in my attic.

GamesBeat: What convinced you to get more involved?

Tippett: We’d been talking a year earlier. I’m very interested in the whole VR thing. Other forms of technology, like the photogrammetry that we use to create these characters—we use real physical objects, but we use photogrammetry to turn that into the digital objects. We were both playing with that stuff. He had another idea that we were working around for about a year, and then he came up with this idea, so he said, “Hey, you got any monsters?” The proof of concept led to—it wasn’t a protracted design thing. We had all the characters.

Above: Sculptures galore adorn the workshop at Tippett Studios.

GamesBeat: How long does it take you to come up with one new creature, one new idea?

Tippett: It really depends. I tend to work pretty fast. Usually it’ll start with a very vague concept. The stuff I do for myself is very different than what I do in my day job, where I’m working with producers, directors, writers, developing something very specific that has to fulfill the functions of a script and the director’s objectives and all that stuff. It’s a different way of making things.

The stuff I do for myself comes from an unconscious sphere. It’s not production-driven. If I’m working on a movie, you start here and the release date’s there. You have to do it all in between there. The kinds of things I’m interested in making, I’m interested in making them over a long period of time, where I have a great deal of time to make mistakes and let mistakes guide me as far as how I approach the subject matter.

In fact, I’ll consciously set up scenarios where I have an image for something, but I don’t know how to do it. I’ve always been interested in things, in materials. Not that interested in the digital side. It’s almost an animistic point of view. Without getting too spiritual or anything, it’s like the objects and materials talk to you. They tell you what they want. You’re operating a bit more like an interpreter, not imposing your intention totally on stuff.

You go back and look at a lot of writings on creativity, back to Bach or Mozart or even Picasso, they’ll be talking about their creative process and a lot of times—Mozart would say it came to him from God. “All I did was interpret it. I didn’t do anything. I just wrote it down.” In some ways it’s like that, like channeling this other thing. What I’m interested in are things I haven’t seen before, experiences I haven’t had, as opposed to a franchise kind of thing.

Above: Phil Tippett’s creatures.

GamesBeat: When did it start occurring to you that the things you build with your hands could be used for some of these other things, besides the movies?

Tippett: I was always interested in movies as a kid. That’s why I taught myself to draw and sculpt and learn about filmmaking. As technology changed, we moved from the photographic era into the digital era, with different tools and different things we could do. Now we’re on the cusp of a whole new world. It’s the wild west. Nobody knows where this stuff is going to go, how to monetize it, even how to get the money to make it. On a creative level, there’s so much room to play.

When we were making Star Wars with George, he didn’t know how that was going to go. Maybe nobody was going to like this thing. Now it’s at this point where it’s created all these franchises. On a creative level the audience has expectations you have to fulfill. That wasn’t something he had to think about with Star Wars.

GamesBeat: You’ve stayed with physical objects a lot longer than some others. Do you feel like something that’s created digitally first kind of looks computerized, versus something physical?

Tippett: Not really? For me personally I just don’t work on a computer. I don’t. I can manage Microsoft Word or Photoshop. Sometimes I do stuff there. But I just don’t like the experience. I don’t like sitting down. I don’t like focusing on one thing. I like to be able to move in the world. That’s a lot of what drives me.

Initially, when we were doing Jurassic Park and Starship Troopers, we built a lot of 3D hand-sculped maquettes. Back then the technology required it. That was the best way to build stuff, because the talent pool wasn’t to a level where you could do it from the start in the computer. But now it is. There are a bunch of really talented, skilled people doing that.

GamesBeat: It seems like if you create it physically, you wind up with something that looks more …organic, maybe?

Tippett: It really depends on the skill level of the artists working with the tools that they’re familiar with. I’ve seen some people do amazing things with computer graphics.

Above: Tippett Studio has handcrafted creatures from lots of movies.

GamesBeat: If the game is successful and they say, “Hey, we need 15 more monsters,” where are they going to come from?

Tippett: Oh, I’ll figure that out. [Laughs] It has to be successful first. I don’t worry about things until I have to worry about them. But I’ve got a lot of stuff. We’re kind of thinking ahead with some of that stuff, thinking about, “What’ll we do if…?” We’ve got some ideas.

GamesBeat: Did the chess set stay with you the entire time, that game from the original Star Wars? Did you ever think that would be a real game?

Tippett: Oh, no. Absolutely no idea. Even when we were making it. It was an afterthought. I got hired to work on the cantina scene with a bunch of other people. We were doing masks and characters for that. George would come over once a week to check our progress. While he was there one time, he saw a stop-motion puppet I’d made when I was a teenager. He said, “Oh, you do stop-motion?” Previously he was going to do the chess scene with actors in makeup and masks. That gave him the idea to do it as a stop-motion thing. It was right at the end of the schedule. My partner Jon Berg and I just banged these things out, really quickly. We went over to the studio and shot it over a few days.

We got on the set and there were no rules for the game at all. It was just for a movie. We said, “George, what do we do?” He says, “Well, this guy jumps in and this guy picks him up and throws him on the ground.” And that was it.

GamesBeat: So you had to build the game and its rules with a whole new set of creatures.

Tippett: That’s Mike’s problem. I have no experience with games. I play checkers with my kids and that’s about as far as I go. I’ve never worked on a game project until now. But it can be a lot of fun.

Above: The workshop at Tippett Studios

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More