Intel chief executive Paul Otellini addressed Wall Street analysts this morning with the message that Intel isn’t a dinosaur clinging to the PC chip market, but a fleet competitor expanding in all directions where computing can be found.

Intel chief executive Paul Otellini addressed Wall Street analysts this morning with the message that Intel isn’t a dinosaur clinging to the PC chip market, but a fleet competitor expanding in all directions where computing can be found.

The world’s biggest microchip maker is not only making faster chips. It is also making them more power efficient, and that is allowing Intel chips to move into mobile devices where low power usages yields longer battery life. It is also moving deeper into the data center and communications infrastructure, as well asinto cars and retail kiosks. For competitors, there is nowhere to hide.

“We’re delivering experiences across the compute continuum,” Otellini said.

In particular, Intel sees growth in thin laptops known as Ultrabooks, mobile devices, and data center chips. The annual Intel analyst day is useful for providing perspective on Intel’s operations. Last year, Intel generated $54 billion in revenue, up from $35 billion two years ago. Its operating income was $17.5 billion, up from $5.7 billion two years ago. Otellini noted that Intel now gives a dividend of 90 cents a share each quarter. Over the past 10 years, Intel has given back $80 billion to shareholders. And while Intel focused on a 100-million unit PC market in 1995, it now focuses on a broader computing market with the potential for billions of units.

Web-connected data centers are creating huge demand for Intel’s server chips. One of the inexorable trends helping Intel is the huge growth of data that is uploaded to the cloud. Seven exabytes of data are created every day, Otellini said. That’s equal to 17,000 high-definition movies uploaded every second. In one minute, 60 hours of data are uploaded to YouTube.

The tectonic plates are changing around computing. In 2011, the U.S. was the No. 1 market for PCs, followed by China, Germany, Japan and Brazil. In 2011, China surpassed the U.S. and Brazil passed Germany and Japan. By 2016, the top five will be China, the U.S., Brazil, Russia and India.

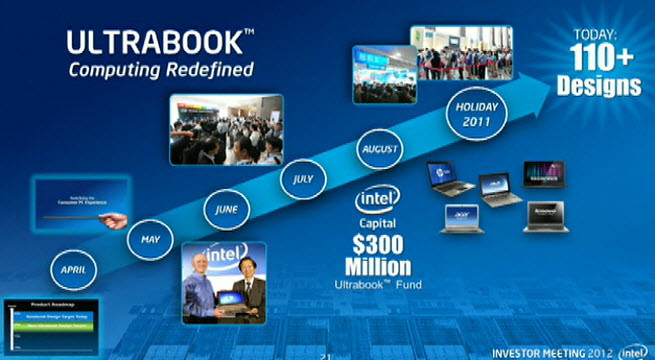

Otellini noted how fast Intel has moved on Ultrabooks, or the high-performance, thin laptops that resemble Apple’s MacBook Air. In the middle of last year, Intel set up a $300 million investment fund for Ultrabooks. It is now kicking into high gear shipping chips based on its code-named Ivy Bridge design, which combines graphics and a microprocessor in the same chip.

Otellini noted how fast Intel has moved on Ultrabooks, or the high-performance, thin laptops that resemble Apple’s MacBook Air. In the middle of last year, Intel set up a $300 million investment fund for Ultrabooks. It is now kicking into high gear shipping chips based on its code-named Ivy Bridge design, which combines graphics and a microprocessor in the same chip.

Those 22-nanometer Ivy Bridge chips are the heart of the new Ultrabooks and enable them to operate on low-power levels that give the laptops all-day battery life. Intel is expecting 110 Ultrabook designs coming to the market by the end of 2011.

“We are on track to meet our goal of 40 percent of the consumer notebooks this fall being Ultrabooks,” Otellini said.

The Ivy Bridge chips will be shipping at 2 million chips a week by the end of this quarter, and they will exceed the predecessor Sandy Bridge chips by the end of this year.

Otellini said in mobile that “we’re just getting started here.” Intel has been criticized for failing in mobile device chips before, leaving the market to ARM-based rivals.

Intel’s first chip for the new generation of smartphones, the Intel Atom Z2460, is getting good reviews. Intel partnered with Google last fall on Android, and it followed that up by scoring deals with Orange, Lenovo, ZTE, and Motorola. All of those partners will use Intel’s chips, and Intel has a mobile payments deal in place with Visa. Otellini said that Intel-based tablets will take off with the launch of Microsoft’s Windows 8 operating system this fall.

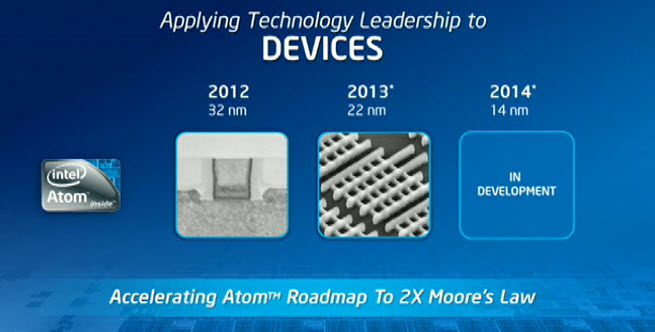

Over time, Intel will move at twice the rate of Moore’s Law (the idea that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every couple of years or so) as it improves its Atom chips. It will move further with miniaturization of its Atom chips as it does with all of its product lines, but it will also move them from older manufacturing processes to the most advanced ones. By 2014, Intel will move to 14 nanometer chips where the circuits are 14 nanometers apart (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter).

Over time, Intel will move at twice the rate of Moore’s Law (the idea that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every couple of years or so) as it improves its Atom chips. It will move further with miniaturization of its Atom chips as it does with all of its product lines, but it will also move them from older manufacturing processes to the most advanced ones. By 2014, Intel will move to 14 nanometer chips where the circuits are 14 nanometers apart (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter).

Moore’s Law, articulated by Intel chairman emeritus Gordon Moore in 1965, has delivered chips that are 4,000 times more powerful than Intel’s first 4004 microprocessor in 1971. The chips use 5,000 times less energy per transistor and are 50,000 times cheaper per transistor. Meanwhile, the cost of factories are skyrocketing. With 200 millimeter wafers (the pizza-dish-size disks that are processed and then sliced into chips), factories cost $1 billion. Now they cost $5 billion. By the time the industry shifts to 450 millimeter wafers, they will cost $10 billion.

With the costs rising, inventions for new ways of making chips are becoming more important. Intel launched such an innovation with “tri-gate” transistors that make use of vertical space. Otellini argues that its rivals will become less competitive in terms of manufacturing chips with economic and volume scale. Otellini foresees a “golden age” for companies that can afford to make their own chips.

Otellini said that chips that are embedded in kiosks or robots or terminals will become smarter, so Intel is labeling this $2 billion a year business as “intelligent systems.” Intel is moving its chips into cars with dashboard entertainment systems, retail kiosks, and communications infrastructure. In the latter, Intel has deals with Huawei, China Telecom and Verizon.

“The world is moving to client-aware computing,” where the network understands the computing device and exploits it if it is based on Intel architecture, Otellini said.

Intel’s acquisition of McAfee and Wind River have contributed about $4 billion a year in revenues. McAfee is now embedding its security functions inside Intel chips.

“We’ll continue to deliver shareholder value through” chip manufacturing, architecture, and new markets, Otellini said.

Speaking about Intel’s overall strategy, Patrick Moorhead, analyst at Moor Insights & Strategy, said, “This makes a lot of sense for Intel because it leverages their strength in the data center. If Intel can tie client processor features to server features like security, this will create in a sense, a ‘lock-in’ that would be difficult to break apart. Intel’s competition knows this and will do everything they can to block these advances.”

As for Intel’s manufacturing advances, Moorhead said that the company is typically years ahead of rivals, but smaller companies such as TSMC and Globalfoundries have found ways to be competitive in the past, even with rising factory costs.

“Regardless, it will be tougher to stay close to Intel on process technology and manufacturing,” Moorhead said.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More