There’s a reason Intel executive Kirk Skaugen showed off his company’s latest server chips inside a bank vault yesterday. He wants to create the impression that the 29 new chips being introduced today are as secure and reliable as they come.

There’s a reason Intel executive Kirk Skaugen showed off his company’s latest server chips inside a bank vault yesterday. He wants to create the impression that the 29 new chips being introduced today are as secure and reliable as they come.

The new Xeon processor E3 and E7 families of chips are aimed at providing a big boost in performance, reliability, security and energy efficiency. Intel says that buying servers with the new chips could pay off in less than a year, especially for all of those recession-weary companies that are still relying on old servers. A single rack of these new servers could replace 18 dual-core Intel servers from five years ago and run on 93 percent less energy. If this pitch succeeds, Intel could fuel a recovery in enterprise tech spending.

The sheer number of chip designs shows that Intel can blanket the entire market for servers, from the low-end models to the high-end supercomputers, leaving very little room to maneuver for rivals such as Advanced Micro Devices, Oracle and IBM.

Intel has been on a roll in server chips since it launched its improved designs, code-named Nehalem, more than two years ago. Last year, it launched the Intel Xeon processor 5600 family, where one 5600 chip could do the work of 15 single-core servers from five years ago. On its “tick-tock” cadence, Intel is introducing a new kind of server chip every year.

Intel has been on a roll in server chips since it launched its improved designs, code-named Nehalem, more than two years ago. Last year, it launched the Intel Xeon processor 5600 family, where one 5600 chip could do the work of 15 single-core servers from five years ago. On its “tick-tock” cadence, Intel is introducing a new kind of server chip every year.

The new E7 chips have as many as 2.6 billion transistors, or basic electronic components. By comparison, Intel’s original 4004 microprocessor from 1971 had just 2,300 transistors, and the Nehalem chips has more than 731 million transistors. Skaugen says you could put one transistor per foot and go all the way to the moon and back and you’d have 2.4 billion transistors used, with 200 million more to spare.

Intel can put more transistors on the same-size chip thanks to Moore’s Law (predicted in 1965 by Intel chairman emeritus Gordon Moore), which holds that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years. Intel is more than matching that prediction now, thanks to the increasing density of memory on each chip. Each chip is built with 32-nanometer manufacturing, compared to 45-nanometer chips that Intel fabricated two years ago.

“We are moving into mission-critical computing, thanks to Moore’s Law,” Skaugen said.

In other news, Intel rival AMD said yesterday that its first 32-nanometer quad-core microprocessors, code-named Llano, are now shipping to customers who will start selling them in the second quarter. The Llano processors are accelerated processor units, (APUs), which combine a processor and graphics in the same chip.

These new server chips are sisters to the family of consumer chips Intel introduced earlier in the year. They feature as many as 10 cores, or computing brains, on a single chip and deliver 40 percent greater performance than predecessor chips. They contain two new security features that ensure high levels of data integrity and server uptime. Each core can process two threads, or sets of instructions, at once.

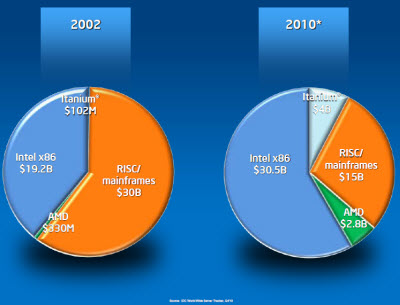

As much as Intel touts the performance and energy savings of its new chips, the company is really hoping that the ability to do tasks that mainframe chips handle — such as virtualization, high-end database functions, encryption and real-time analytics — will help Intel attack the $18 billion market for RISC-based mainframe systems (reduced instruction set computing) that Intel doesn’t yet dominate.

More than 35 systems using the new E3 and E7 chips are ready to ship from 19 computer makers today, ranging from two chips in a server to up to 256 chips in a supercomputer. Those computer makers are leading the charge into “mission critical” computing for internet data centers, scientific supercomputers, and stock market computers.

More than 35 systems using the new E3 and E7 chips are ready to ship from 19 computer makers today, ranging from two chips in a server to up to 256 chips in a supercomputer. Those computer makers are leading the charge into “mission critical” computing for internet data centers, scientific supercomputers, and stock market computers.

Those systems were once solely the domain of RISC chips from IBM and Oracle’s Sun Microsystems business. RISC systems were a $30 billion market in 2002, but have now shrunk to $15 billion, according to market researcher IDC. Meanwhile, systems based on Intel’s Xeon server chips have grown from $19.2 billion to $30.5 billion.

SGI is making the server with 256 chips. It is among the dozen different systems being launched today that Intel says are setting new world records in performance, based on third-party benchmarks. Numerous enterprise software vendors are supporting the Intel chip, including IBM, Microsoft, Oracle, Red Hat, SAP, and VMware. Prices for the E7 series range from $774 to $4,616 in quantities of 1,000. The E3 ranges from $189 a chip to $612. The systems are available now, and 60 products will be ready by year end.

Intel said the E7 chip has about 160 percent of the performance of Oracle-Sun’s t5440 microprocessor and 50 percent of the system cost. And it says the E7 has 600 percent of the performance of the Oracle-Fujitsu m4000 system and 50 percent of the system cost (based on list prices from those vendors). Skaugen said Oracle’s 11g database can run 10 times faster at encryption tasks using the E7 series chips.

Skaugen said the Intel-based systems with the newest chips could pay for themselves within a year, given factors such as lower energy costs and the ability to get rid of a bunch of servers. He noted that 20 percent of the server base in the world runs on single-core chips and 50 percent run on five-year-old dual core chips. An E7 chip could do the work of 29 single-core servers.

Intel had three server customers ready to endorse the new chips. David Kennedy, director of infrastructure for NCH, said his company would adopt the new E7 family because it saw a 300 percent improvement on Oracle database applications. With lower maintenance costs, Kennedy said his firm could avoid $5 million in costs by switching 150 servers from IBM to Intel.

Vishal Mehra, senior manager for IT at chip maker Texas Instruments, said his company operates 12 data centers with more than 12,000 computing cores. Over time, he said TI would switch over to Intel-based systems.

And Bernie O’Connor, director of information technology at global distributor Anixter, said his company would switch to Intel’s new server chips because of the higher average availability time before failures. His company has more than 1,000 servers.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More