Many of Kabam‘s social mobile gamers play for three hours a day, seven days a week. But sometimes, they can complain for just as long.

That’s the blessing and the curse of Kabam’s success in the strategy-gaming niche, where it has published titles like The Hobbit: Kingdoms of Middle-earth. These games have landed Kabam in the top-10 grossing games on mobile platforms, and they’re just part of a larger portfolio of titles that are spreading the company’s risks and creating opportunities for breakout successes.

But success comes at a price. In Kabam’s free-to-play games, only a small percentage of players pay for things. And those folk are very demanding, particularly when they see changes in the games that they don’t like. Andrew Sheppard, the president of Kabam Studios, has to think about this design challenge as he takes the games of the $300 million company to the next level.

I interviewed Sheppard onstage at the Mobile Gaming USA event this week in San Francisco. Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

GamesBeat: Andrew, since you’ve been there four years, can you tell us what it was like when Kabam got started?

Andrew Sheppard: I joined Kabam about four years ago, as you say. At that time Kabam was about 30 folks. The kind of legend that we talk about is, the original Kabam was a company called Water Cooler. They built social and community apps for Facebook. They had significant success early on, when the platform was a very open space, getting up to 60 million uniques off just community apps that went viral.

Then the ad markets hit a difficult patch, and Kevin, our CEO, realized the opportunity to produce a kind of content where consumers would pay you directly to participate in the experience, and ideally – in the context of free-to-play – pay only when they felt the content was good enough to warrant paying for it. He felt that was a path for the company that would align it more with the consumer, and give the company much more durability.

In 2009 they started building Kingdoms of Camelot. I joined in December of 2009, when the game was still in beta. It was a small office on Castro Street in Mountain View, right above a dim sum shop, which you couldn’t avoid. You had to take the elevator up and be locked in the car with dim sum. But over the next four years, we grew substantially, from a 30-person shop in Mountain View to a 100-person team in Redwood City, and then to a 350-person team in San Francisco and Redwood City, and then today an 800-person company.

GamesBeat: How quickly did you know that Kingdoms of Camelot was your big hit?

Sheppard: In all honesty, when Kevin and I were talking about the role—I took the role more on instinct than I would have historically. But I had a feeling, when I first looked at the game and Kevin and I discussed the early high-level metrics, that it would be really successful. But at that time we didn’t really know.

I could see right away that the community was alive. Not only were there lots of blogs about the game, but inside all of our games, we have—We were the first company to push what would be typically classified as MMO features – alliances, chat, group messaging – into a browser and now a mobile game. The confluence of, this is a game built by a group of passionate developers who love these games, and the users inside the game are telling me it’s great, and it’s on this Facebook platform that doesn’t have any core games currently and is growing like a juggernaut, it felt like the right intersection of forces. We had the platform, the right alignment with the consumer, and developers who love this type of strategy game.

When I joined, I remember my revenue chart for the year was $2 million. We beat that by 16 times the next year.

GamesBeat: You had an interesting dynamic in Kingdoms of Camelot, where you had these 100-person clans back then. Somebody would cause trouble, and then everybody would attack that one person. All 100 would pile in at the exact same moment and you’d have a giant battle. But there was no animation. It’d be over in an instant. You’d get these spreadsheet results back. And people loved it.

Sheppard: My arc through gaming has gone from working on publications like Gamespot, then moving to traditional triple-A companies like Electronic Arts, and then ending up in web and now mobile. I remember a lot of my friends who were still working at traditional game companies fell into the camp of just being opposed to social games. Our game, although a core game, was classified as such.

Certainly web technology wasn’t at the point where you could visualize combat to the degree that we wanted, or battle resolutions, or even the way that players made consequential choices in their universe. But speaking to the power of the core gameplay mechanic, especially for strategy gamers—Strategy gamers care enormously about being able to set up a number of configurations for how they want to participate in the world and then seeing how those actions play out, either in a turn-based fashion or an incidence-based fashion. People were able to develop quite complex emergent gameplay patterns with their alliances to take down competitors or, in the case you described, encourage people to act in socially constructive ways.

Games do go through, over the life cycle of a server, these different states of being in complete chaos – almost like Wolf Run, or an early Automata type of thing – to being in a steady state. It’s fun to see that play out and change over time.

GamesBeat: And you’re able to reskin these games – the same game – with different themes like Rome or Atlantis.

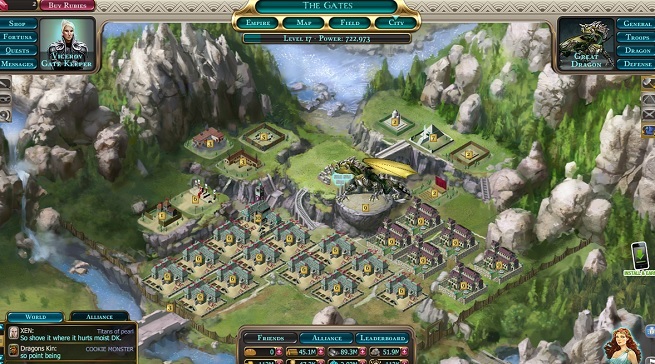

Sheppard: Early on, we went down the path—on the Facebook web, we had a couple games that were very similar. We had Kingdoms of Camelot, Glory of Rome, and Global Warfare. What we learned by doing that was, there wasn’t enough difference in the core gameplay to justify these latter games existing at scale. What you’ve seen with Dragons of Atlantis and Kingdoms of Camelot for mobile and The Hobbit is, we’ve gone much more heavily into adding differentiating gameplay. Although it’s very subtle, we’re changing the configuration of how the battles work and the way the universe coexists to drive a different type of emergent behavior that’s targeted toward the audience.

The Hobbit is a strategy game, and we classify it in the subgenre of empire strategy game. But it has factions, and it increasingly has a feature set that’s more appropriate to a mass market audience. Kingdoms of Camelot is much more hardcore. It’s kind of a ren faire audience. They’re looking for a lot more lore about Camelot or Avalon or Arthur. We try to invoke that in that universe.

GamesBeat: And then what you get out of this is loyal users. They’re playing six days a week sometimes.

Sheppard: Absolutely. Across Web and mobile, although the stats are somewhat different, we find that our average paying user plays three hours a day, six days a week. It’s astounding, because when you think about the battery life on some phones, they don’t get three hours if you’re using them constantly.