There’s an easy way to get your computer infected with a virus. You can click on the free antivirus software offer in your email and download it. Or get on a free tech support service chat session where you ask a security expert about how to protect your computer. The tech support expert then gives you a file to click upon and clean your computer.

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":203334,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,security,","session":"C"}']This kind of scam is around five years old, but it is becoming more and more sophisticated, according to a presentation given Tuesday in San Francisco by antivirus experts for Kaspersky Labs, a Moscow-based company whose software protects more than 300 million computers around the world. The presentation showed there are still plenty of things to worry about when it comes to protecting your computer from malware, or malicious software — a category that includes worms, viruses, and other hostile pieces of code.

The tech support scammers mentioned can talk to you in just about any language and are available to hold a conversation 24 hours a day. (If only real tech support were so reliable!) When they offer to help you protect your computer, they can give you a virus payload that appears to clean the malware off your machine but actually infects your computer with new malware.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

One problem is just the sheer volume of bad stuff available on the Internet. From 1992 to 2007, antivirus researchers found 2 million unique pieces of malware. But in 2008 alone, they saw 15 million and in 2009, the number was 33.9 million. And, as the scams mentioned suggest, the malware vendors are getting more clever about fooling people into installing the malware on their computers. The tools for creating viruses automatically are running ahead of the ability to stop them and get rid of them; just collecting “digital signatures” of viruses isn’t enough anymore.

Nicolas Brulez, a senior researcher at Kaspersky, said he has watched “scareware” — fake antivirus software which tricks people into downloading a virus disguised as antivirus software — evolve since 2006. It has sprouted variants such as fake spyware removal tools, fake registry clean-up software, and even fake technical support chat sessions. Social networks are now becoming great channels for spreading viruses among people who trust each other.

David Emm, U.K. security researcher for Kaspersky, said that the criminals are reaping huge bounties and they’re creating “drop zones,” or online storage caches on the Web that store the things the criminals steal. The average amount of data in the drop zones is 14 gigabytes of data across 31,000 files. That gives you a sense of how much data is being stolen through all of the viruses, worms, and trojan horses out there. The malware worms its way into users’ computers through vulnerabilities in their applications, rather than in the browser or operating system only.

All of the compromised computers are being turned into cyber weapons as well. These zombie computers have become parts of botnets with millions of computers. The cyber criminals control the botnets and rent them out to the highest bidder, who will often use them to shut down web sites that don’t pay extortion money.

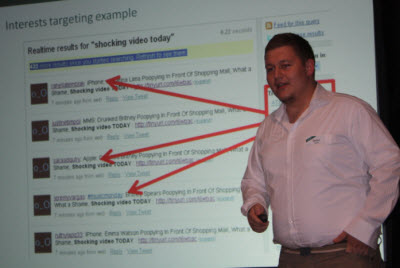

One of the newest forms of attacks is the “targeted attack,” like the Operation Aurora that targeted Google’s computer networks in December. In such attacks, the cyber criminals target employees who aren’t careful. They collect information on the employees via social networks. Then they target malware at the employee in a way that exploits that employee’s own social interests; then the employee unwittingly compromises the company’s network, said Stefan Tanase (pictured at top), a senior antivirus researcher for Kaspersky in Romania.

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":203334,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,security,","session":"C"}']

Targeting can exploit someone’s language ability or geographic location. For instance, when targeting victims in India, malware writers can create a fake Reuters story that says there were “explosions in Bangalore.”

One of the latest worms is Stuxnet, which targets industrial computer networks which use Siemens’ SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) software. The networks in places such as factories, chemical operations, or power plants are typically not connected to the internet. But Stuxnet spreads via a universal serial bus (USB) stick. Someone leaves a bunch of USB sticks in a company cafeteria and users then pick them up and put them in their machines. That leads to a network infection. Microsoft published a patch to help deal with this threat a couple of days ago, but Stuxnet has already spread far and wide. Some of the countries hit particularly hard are India, Iran and Indonesia.

One of the clever things about the Stuxnet malware is that it creates a fake digital signature. Digital signatures are certificates for web sites that verify that they are who they say they are and are malware free. Antivirus software tends to give a free pass to any software that shows it has a digital signature certificate. Realtek and Jmicron are a couple of companies that had their digital signatures compromised.

Digital signature certificates are part of a security system called “whitelisting,” or saying that a site is good rather than “blacklisting,” or saying that certain code is bad. With fake digital signatures, the malware writers erode the system of trust that whitelisting otherwise enables.

[aditude-amp id="medium2" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":203334,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,security,","session":"C"}']

“It makes us rethink the way we process files with antivirus checking,” Schouwenberg said.

Stuxnet is so sophisticated that Kaspersky believes that a “nation state” is responsible for its creation, not just an underground mob, Schouwenberg said. Sounds depressing. Is there any hope that the cyber criminals can be defeated? I don’t think so.

But the antivirus companies such as Kaspersky keep trying. Kaspersky is introducing new antivirus software for sale on Aug. 16.

Kaspersky’s Peter Beardmore said, “It’s our job to out-innovate the bad guys and at the same time keep the software easier to use.”

[aditude-amp id="medium3" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":203334,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,security,","session":"C"}']

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More