Grant funding versus the market

White told me that Filament is actually starting to move away from the grant model of funding, where it’s so easy to get caught up in the application process that studios can forget the needs they should be fulfilling.

“We probably won’t be applying for any more grants in the immediate future,” said White. “Like any funding, when you focus your efforts on that source of funding, you craft all your thinking about why you will succeed around what you think that fund wants to hear. It’s important that we start to do products that are extremely market driven.”

So Filament has been listening to teachers about what they want from educational tech. As a result, it’s currently building a creative tool called Discussion Maker that supports classroom discussions, making them easier and more fun for kids. By actively listening to the market — in this case, teachers — White says Filament has not only made discussion more engaging for kids, but it’s also solved a problem that teachers had in trying to implement “21st Century pedagogy.”

But even with this market-driven approach, making money in the educational arena is still damn hard, especially if you need to make it quickly.

“If you were Venture Capital funded, and you had a short runway, and you had a to make a profit out of something quickly,” said White, “I think you’d be in trouble.” Turning a quick profit in the educational space is “frankly impossible,” he reckons.

Part of the problem is that teachers are usually the biggest advocates for your games, but they rarely hold any buying power themselves. “I think the landscape would be different if teachers had a bunch of money they could spend on things they think are interesting,” said White.

The distribution dilemma

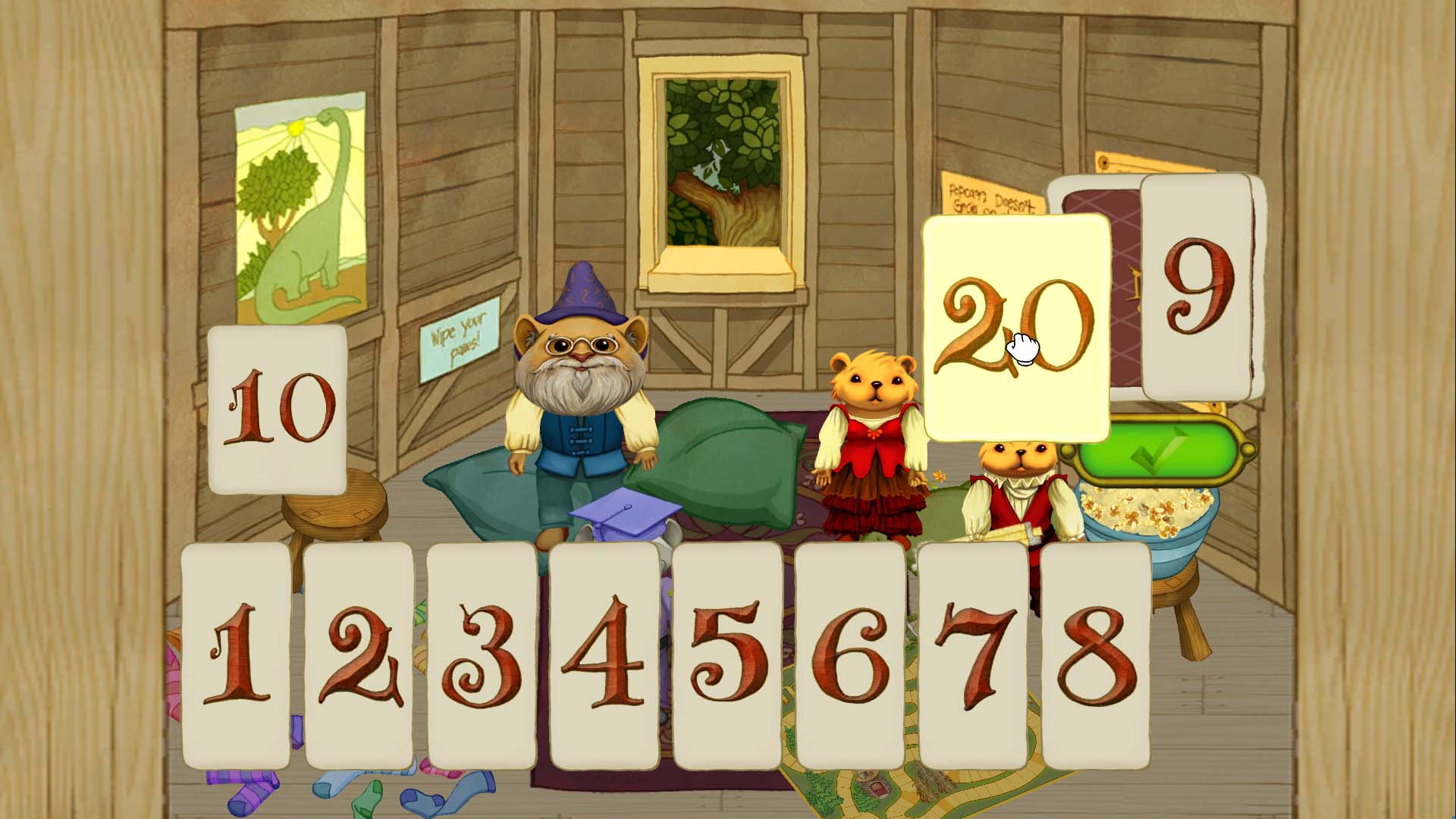

Marshall Gause came to the educational scene from a console background, via social games. Back in the day, he made games for the Nintendo 64, PlayStation, and Sega Dreamcast. More recently, Gause, the president and creative director of Oregon-based studio Thought Cycle, has helped create the PC and tablet game NumberShire, an educational title for kids in K-2 who are struggling with basic number concepts.

Also a recipient of Department of Education funding, Thought Cycle has found that sales and distribution are the two toughest hurdles for educational studios, particularly those that are new to the scene.

“The education market is a long, slow cycle,” said Gause in a Skype chat. “It takes them a while to make decisions on what they’re going to use and to adopt them. We’re hopeful that the 60 districts that are using NumberShire now are going to, in the fall, re-up and have more schools within their districts using it. Schools by their nature are risk-averse in terms of purchasing; they have to be.”

The trickiest part of the sales process, says Gause, is that you’re so far removed from your user. The student, who’s the person you’re trying to engage with the game, has no buying power, and often neither does the teacher. “Then you have your superintendent or administrator who has the purchasing power but is three layers removed,” he said.

“There’s money there,” said Gause. “But there’s this three layer or more purchasing structure. That’s why so many of the big publishers still dominate.”

Thought Cycle partnered with the University of Oregon to research and create NumberShire, and it’s now using the University’s online marketplace to help sell to schools. It’s just one of numerous ways that schools and districts can buy educational software, including the Filament Games store which will soon be selling “high quality” third-party games alongside its own titles. As Gause puts it: “Everyone’s trying to be the Steam for educational games.”

The government perspective

I reached out to Edward Metz, the SBIR program manager at the Department of Education to ask why the government’s putting such stock in educational games and investing so heavily in their development.

“From my perspective, the discussion on games for learning has shifted,” said Metz via email. “10 years ago, the question was, ‘Are games appropriate for education?’ Now, that question has been replaced by, ‘How can games be optimized to impact learning — both in providing individualized learning opportunities for students and in being integrated into classroom practice and providing real-time data that teachers can use to guide instruction.’”

Metz pointed out that the quality of game proposals has increased tremendously over recent years, and this is partly why more gaming projects are getting grant approval. “More game developers are now basing their gaming concepts in learning theory,” he said. “And more developers are partnering with education researchers to iteratively develop the games based on feedback from initial student and teacher users.”

All developers that get funding approval have to commit to a pilot study that shows their game prototype is working as intended,and that teachers and students would find it useful. They then need to complete a second research phase during full development in order to secure the bulk of the funding. This again involves testing the game with a group of students to see how well it’s working.

Above: Schools are starting to get devices like iPads that they need to figure out how to best use.

Thought Cycle went through this process with NumberShire, and kids using it showed good improvements in basic number skills over the research period. Gause said it was something they had to do, but it was still a somewhat nervous testing period. “We were going to have to live with the outcomes,” he said. “We really had to make sure we were building something that would be effective. We had to do it, we felt it was the right thing to do, and we felt it added value to [the game] as well.”

Gause thinks that such empirical testing is going to be more standard for educational games going forward. With more and more titles out there, he says that “some measure of efficacy is going to be important.”

The future of educational games

Speaking to Jean-Baptiste Huynh, it was clear he considers the learning games market to be something very new. He was keen to differentiate games that actually teach kids something from those that are simply used for assessment or practice. “There is no learning industry, almost, in games,” he said.

Gause also sees educational games’ future being very different to its present, but he says it’s going to be a tough journey ahead and will require a different way of thinking.

“It needs to be a holistic thing,” he said. “There are games like DragonBox which I think is really great. They’re out there, but they’re sort of the perfect storm: Building something that’s engaging and has educational value.”

And Dan White thinks that developers will start to make money from educational games, just not yet. “I do think it’s possible,” he said. “I don’t think it’s possible quite yet; I think it’s a long game.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More