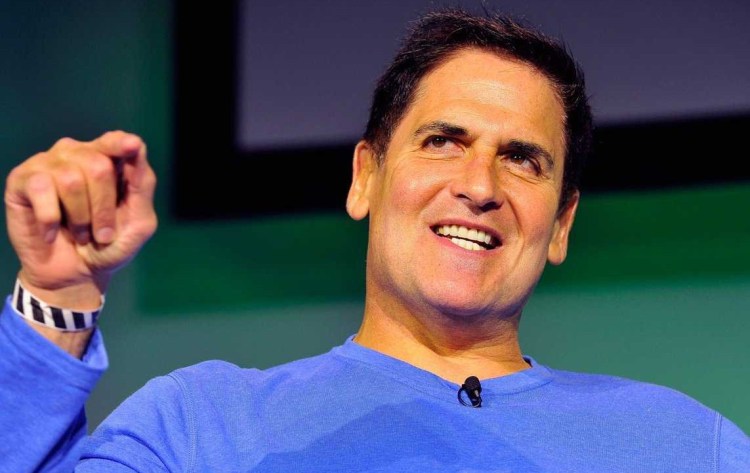

Mark Cuban wrote a blog post Wednesday explaining why this tech bubble is worse than the bubble experienced in 2000. He says that investors today are investing in early-stage tech deals in the hopes of finding the next Twitter, Uber, or Facebook. That in itself isn’t the problem. The difference is that, in contrast to 2000, we’ve made this high-risk startup investing accessible to far more individuals.

Cuban points out that one of the major differences between now and then is the access that investors have to startups. Five years ago, angel investors didn’t have as much access to startups because the VC community was an insiders’ club. If you didn’t have the right network and $50,000 to invest, you couldn’t participate. Over the last several years, funding platforms and general solicitation rules have provided access to investors and made it possible for startups to introduce themselves to a more diverse crowd of capital sources.

Today, if you are an accredited investor and have $5,000 to invest, you can choose from hundreds of opportunities via equity crowdfunding platforms. With dozens of legitimate equity crowdfunding platforms in business, investors can consider venture capital investing as never before possible. This has opened access to investors beyond Silicon Valley; and every day, there are new angel investors emerging, hoping to find a unicorn.

But these new investors need support, guidance, and resources to fully appreciate the implications of this brave new world. Once they make that investment, they have to live with it for a long time; investors must do their homework, not only about the startup in which they are investing but about the platform through which they are participating.

Thus, the challenge in facing this next bubble has to do with liquidity. That there is no liquidity for private companies. Once you make your investment, you can’t get your money back unless there is an exit, which could be 7 to 10 years away.

Before considering yourself a startup investor, ask these important questions:

1. Do you understand the risks? The majority of startups will fail. If you can assess the risk associated, understand the worst case scenario, and can live with those results, you are ready to be an investor.

2. When do you need the capital from your investment? If your expectation is that you will get your investment back within five years, you shouldn’t invest in early-stage startups. Later-stage pre-IPO companies might be a better fit for your financial goals. If you can write the check and not expect a return for seven or more years, then your expectations are in line with early stage investment returns.

3. Do you have enough capital to make multiple investments? When you invest in the public market, you don’t want to invest all of your capital in one stock. Apply this same logic to startups. The industry-wide consensus is that 70-80 percent of startups fail, 10-20 percent will be break even or return something, and 5-10 percent are going to provide enough return to pay for your losses.

In his post, Cuban talked about the issue of liquidity not just because of the length of time involved in investing but also because liquidity is a major factor when assessing a company. As you start investing in startups, it should be clear to you how an opportunity is situated: How far into that lifecycle has the company progressed? Is it on track to reach exit possibilities? If not, what gaps might it need to overcome, and what are the implications of it missing that exit point? Investors in the dark about liquidity should not be investing.

Cuban made a statement about how most new investors who use equity crowdfunding platforms are currently underwater in their investments. While these investors might not have liquidity options at the moment, frankly this supposition varies from platform to platform. If you pick the right platform, one that is curating deal flow and working with investors, the quality of deals will be better and investors will be building diversified portfolios that accommodate the risk.

While liquidity is going to be an issue for the average investor, an educated accredited investor should only be investing money that they can afford to lose. These investors are not typically looking for immediate liquidity and understand that their money will be tied up for a long period of time. They are looking for more companies, access to curated opportunities, and as they participate in more startups, they increase the odds of a winner coming out of the group.

Bill Clark is the CEO and founder of MicroVentures, an equity crowdfunding platform. You can follow him on Twitter @austinbillc.