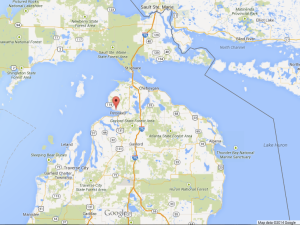

Harbor Springs is one of those sleepy, sheltered towns in northern Michigan where not much happens.

Fewer than 2,000 locals spend the summers catering to the influx of tourists. Then, they must conserve their pennies for long and grueling winters. For many Harbor Springs residents, it’s a challenge to make ends meet. At 11.6 percent, the unemployment rate in Harbor Springs is far higher than the national average of 8 percent, and job openings declined almost three percent in 2013. The median household income is just $40,000.

But something changed last summer with the sudden arrival of 15 energetic, young technology entrepreneurs from as far as San Francisco and Taiwan.

These founders were in town for Coolhouse Labs, a new startup accelerator headquartered in a former retail office on the north shore of Lake Michigan’s Little Traverse Bay.

Coolhouse is the brainchild of a local resident, 27-year-old Jordan Breighner, who wants to fight the brain drain of local talent into finance and consulting gigs in cities like Boston, San Francisco, and New York.

Harbor Springs may seem like a random choice for a startup accelerator. But its founder has a plan that is far more pragmatic than you might expect.

I met Breighner for coffee in downtown San Francisco and expressed a few concerns about the program. Harbor Springs is out of the way. How does he expect founders to relocate here, even for the summer? We already have a glut of accelerators. Why do we need another?

Breighner said he does not expect to get rich like the founders of Y Combinator or build a thriving startup ecosystem in Harbor Springs. His more immediate goal is to generate enough excitement in town to keep twenty-somethings from leaving Northern Michigan generation after generation.

Breighner is hopeful that the youngest local residents of Harbor Springs (those who grew up in the area) might opt to stay, potentially to work at Coolhouse or to start an Internet business of their own. If Breighner can convince entrepreneurs to keep coming back to the area each summer, larger tech companies may follow suit, he says. Eventually, more established businesses might even relocate to the area, attracted by the affordable housing and nascent startup scene.

“Before starting Coolhouse, I couldn’t stop thinking about how we could create an environment where young people wanted to stay,” Breighner said. “And this could be crazy enough to actually work.”

He’s off to a good start: Tarik Dixon, the Manhattan-based founder of TRNK, a home furnishing site for men, was one of the first founders to enroll in the program. He likened the experience to an “incredibly intense adult summer camp.”

Intense, but quirky. Dixon recalls how locals mistook the Coolhouse offices for an Internet cafe and a computer repair store. One elderly lady brought in her Kindle because she thought it was broken. Dixon assisted her by turning it on.

The road back to health

Like most of his peers, Breighner moved out of Harbor Springs as a teenager. He had big dreams to make it as a professional ski racer, eventually finding his way to the University of Utah and its illustrious ski team.

After graduating, Breighner joined Barack Obama’s digital campaign team to help the promising young senator from Illinois get elected. After the grueling 2008 campaign, he landed a full-time gig at the White House to work for President Obama and relocated to Washington, D.C.. A few years later, he was offered a job at the Department of Homeland Security.

Finally, last year, after a short stint at a communications firm in New York, Breighner made the decision to put his career on hold. He couldn’t banish his hometown from his mind.

Breighner reached out to friends in the political world to pitch a few ideas, including a summer startup accelerator. The accelerator model seemed viable. In a matter of months, he was able to loop in advisors from the D.C. and New York tech scenes, including Automattic‘s director of platform services Peter Slutsky.

Most of these supporters grew up in the Midwest and continue to have a strong personal connection to the region.

Slutsky hails from the East Coast. But he has a passion for backing entrepreneurs living outside of the usual tech hubs. After hearing Breighner’s vision, he offered to dedicate several hours a week to mentoring the first batch of entrepreneurs.

“Michigan has a legacy for being a place where big things happen, and it’s been hard to see the state and the people fall on hard times in the changing economy,” Slutsky wrote to me in an email.

“Ultimately, the road back to health for the auto [industry] and for the workforce in general will be via new technologies and new tech jobs.”

“It won’t be easy”

Coolhouse may have a unique vision and set of goals, but it follows a fairly traditional accelerator model.

Founders receive housing, access to a mentor network, and $25,000 in funding. All this comes in exchange for 6 percent equity.

Coolhouse can’t compete with programs like TechStars or 500 Startups when it comes to an investor and mentorship network. But Breighner and some of the Coolhouse alumni do see some advantages to holing up in a small town for the summer.

For Dixon, that summer in Harbor Springs forced him to “take a step back” and focus on his company’s product.

“We actually paused on the website we had up at the time and instead invested the time in working toward something bigger and better than what we originally conceived,” he said.

“Had we stayed in New York, I think we could have ended up being more reactionary than forward-looking.”

Another benefit for entrepreneurs: Unlike Silicon Valley, Harbor Springs isn’t filled with early adopter types who rave about tech. Most people face financial hardship and have more pressing concerns than attending tech launch parties. According to Breighner, the largest employer in town is the city itself.

“Silicon Valley is rich and can feel like a bubble, so part of what we’re trying to do is get entrepreneurs close to people who are struggling,” he said.

Some of the entrepreneurs were noticeably more considerate by the end of the summer with a clearer set of priorities, Breighner said. At the very least, “we realized how to better articulate our vision to varied audiences,” Dixon recalled.

Likewise, the Harbor Springs locals were exposed to some of the opportunity in the tech sector.

“Jordan is bringing some young people in those technology-based fields to the area — and that’s very positive,” said Lindsey Bur, an assistant general manager at one of the town’s most popular restaurants, Stafford’s Pier. I spoke with Bur, a friend of Brieghner’s mother, during a break from a busy shift.

“But what he’s trying to do won’t be easy in a town that isn’t accustomed to change,” she warned.

“We hope for better things”

Change doesn’t happen overnight. Breighner recognizes that it will take time before people appreciate — or even understand — his mission.

“I find myself spending a lot of my time explaining what an accelerator is, what a startup is, and why I had brought all these tech kids and their computers to our town. People think I’m nuts, but I’m probably fine with that,” Breighner said.

But Breighner has found support from a contingent of residents. The Internet cafes were packed to the brim with tech nerds last summer, a positive sign for some residents. Bur said she supports any program that would entice young people to stay put, whether it’s tech or not.

“It’s really a problem throughout Michigan [that] our young people are leaving,” she said. “We really need to bring some diversity to the area, especially in the off-season.”

Brieghner isn’t the first to bring a touch of Silicon Valley to a small town.

Bradford Paul, the deputy executive director for the Association of Bay Area Governments, a regional planning agency in Silicon Valley, hails from an old industrial town, Fall River, Mass. Paul is plotting a similar initiative for Fall River, but he wants to do more than prevent the brain drain. Paul believes he can reverse it.

“People moved out of their small towns due to the lack of jobs,” he said. “But we should be tapping into the emotional connection of our most successful former residents and creating reasons to bring them back.”

Some 280 miles away from Harbor Springs in Detroit, that city is also undergoing a similar shift. Today, residents are still suffering from the highest number of violent crimes in the country, and the unemployment rate has been dangerously high in the past decade, peaking at just shy of 25 percent in 2009. As Coolhouse mentor Peter Slutsky relayed to me, city officials are realizing that Detroit can’t survive, let alone thrive, by relying on the auto industry alone.

But in recent years, tech entrepreneurs have relocated to the region, in part due to the efforts of Detroit Venture Partners, a local firm founded by the likes of ePrize founder Josh Linkner and Dan Gilbert, founder of Quicken Loans.

“There is an opportunity to really stand out and leave a fingerprint while turning around a great American city,” Linkner recently told Forbes.

Jason Mendelson, a metro Detroit resident and a founder of Foundry Group, a venture firm in Boulder, Colo., recently said he’s noticed the seeds of a genuine entrepreneur ecosystem in parts of Michigan, especially in Detriot. Dozens of Internet businesses, co-working spaces, and meetup groups have sprung up in the downtown area. Many of these startups are well funded and are hiring like mad.

For bright young people raised in small towns like Harbor Springs, Detroit offers an increasingly viable place to start a career. It’s no longer necessary to move out of state to make a decent living.

This newfound optimism brings to mind the town’s 200-year-old (but remarkably prescient) motto: “We hope for better things; it shall rise from the ashes.”

Turkey dinners once a week

Back in Harbor Springs, Brieghner is preparing to welcome the next batch of entrepreneurs. Applications for the 2014 class are open, and close on April 15, 2014.

He said he’s slowly winning over some of the town’s most influential residents.

Shortly before we wrapped up our interview, he shared a story about Mary Ellen Hughes, the eighty-something owner of popular local eatery, Mary Ellen’s Place of Harbor Springs.

Hughes, a prominent figure in the town, heard complaints about how these young visitors were taking up the coveted parking spots. But, willing to give Breighner the benefit of the doubt, she attended one of the Coolhouse networking events.

“Mary Ellen spoke to some of the young entrepreneurs and just couldn’t get enough of their energy,” Breighner recalled.

“She called me to offer us the extra room in her house, and she plans to cook us a turkey dinner once a week. I can’t imagine anything more enticing than that.”

Apply here for the upcoming cohort at Coolhouse Labs.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More